Bishop Athanasius Schneider on the Blessed Sacrament

We cannot dispense with bodily signs of reverence and respect, because He is bodily present; the God-man is truly present.

Above: Athanasius Schneider preaching in Steubenville.

Editor’s note: join the Crusade of Eucharistic Reparation, called by His Excellency Bishop Schneider.

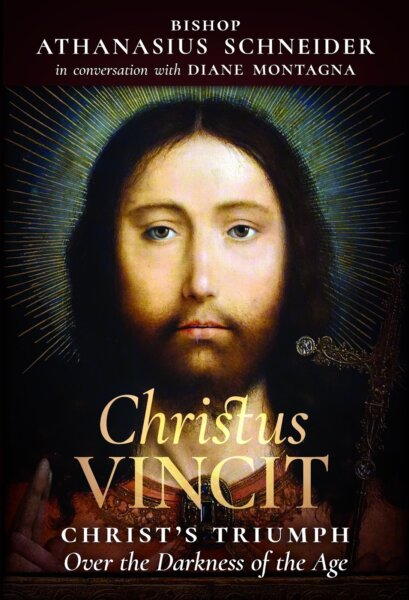

An excerpt from Christus Vincit: Christ’s Triumph over the Darkness of the Age.

Diane Montagna: Your Excellency, you said earlier that the way out of the current crisis in the Church is to “rediscover the supernatural” and to “give primacy to the supernatural in the life of the Church” through a renewed focus on prayer and the Holy Eucharist. Can we now return to the mystery of the Real Presence, and discuss its importance?

Bishop Athanasius Schneider: When we speak about the Eucharist, we have to focus on the essence of the liturgy, on the mystery of the Eucharist, and this is Christ—the living Christ, our Incarnate God, who is really living with His mind, His heart, His soul, and His divinity in the sacrament of the Most Holy Eucharist. But in this mystery, He is veiled, as His divinity was veiled when He walked on the earth with His people, teaching and speaking with them. Since He was so simple and looked like an ordinary man—though the fullness of divinity was present in Him—many people did not recognize Him and rejected Him—the Pharisees, and scribes, and others—because of His humble appearance. St. Paul says of Our Lord Jesus Christ, “He took the form of a servant, being made in the likeness of men, and in habit found as a man” (Phil 2:7).

In a deeper and more radical manner, the same happens in the mystery of the Eucharist, which is an extension of the Incarnation. The Incarnation is continued because now not only is Christ’s divinity veiled by His humanity, but the Eucharistic species of bread and wine veil both the humanity and the divinity of Christ. Christ is veiled, but He continues to be the same; He lives here on earth in the same reality of His Incarnation, but in a different mode. It is now a sacramental mode. His humanity in the Eucharistic is already a glorified humanity, but the glorified humanity is real and can be touched. When Jesus rose from the dead He could be touched; He had a real but transfigured Body. The same is true of the Eucharist: His real body, real soul, and the whole plenitude of His divinity are veiled under the appearance of a small piece of bread.

This presents a continuous challenge to our faith, our love. We are challenged to renew our love for the Incarnation, by continually exercising our faith when we see the consecrated Host. This is our Incarnate God: et Verbum caro factum est: et habitavit in nobis, “and the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14). And now He dwells among us even more deeply and more humbly and more mysteriously — really, in the same realistic way that He walked on the earth, but in another mode. It is real; that is why we speak of the Real Presence—I want to stress this point. This is our faith: that under the veil of the Eucharistic species of bread and wine, the plenitude of Our Lord’s humanity and divinity is present. It should touch the deepest depths of our soul and provoke in us a corresponding attitude of soul and body, because this is the Incarnation. We cannot dispense with bodily signs of reverence and respect, because He is bodily present; the God-man is truly present. Concrete gestures of worship, adoration, and awe are the logical consequence of our faith.

DM: And when we dispense with these gestures, faith in the mystery is weakened?

AS: Yes. When we diminish the exterior signs of awe, sacredness, and reverence, in time it quasi-necessarily diminishes our faith in the Real Presence of Our Lord and in His Incarnation. These are connected. Every time we diminish our respect and our awareness of the presence of Christ in the sacrament of the Eucharist—the real, full, substantial, and divine Presence—we diminish at the same time our faith in the Incarnation itself. Faith in the Eucharist and faith in the Incarnation are inseparably linked. Thus, it is a continuous act of faith in the Incarnation and in the supernatural because it is supernatural, because the divinity is so close to us. In the sacrament of the Eucharist Our Lord deigned to veil Himself beneath these external, weak elements of matter. There is nowhere in the entire world, in the entire history of the world, in the entire universe, where God is so close, where the divinity is as close to His creatures, as in the mystery of the Eucharist.

In the Eucharist, only the external elements of the matter, which are called the “accidents,” persist, while the substance of the elements is transformed into the substance of the Body and Blood of the sacred humanity of Christ and, through the humanity, the divinity of Christ is also present. In the Incarnation, God inseparably united His divinity to our human nature: both natures are united in the Son, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity; we call this the hypostatic union. In the Eucharist, this hypostatic union receives a new aspect. The accidents of bread and wine are associated with the substance of Christ’s Body and Blood and thus are related to His Divinity in a mysterious and unspeakable manner. St. Thomas Aquinas says that the Godhead of Christ is in this sacrament from real concomitance, “for since the Godhead never set aside the assumed body, wherever the body of Christ is, there, of necessity, must the Godhead be; and therefore it is necessary for the Godhead to be in this sacrament concomitantly with His body. Hence we read in the profession of faith at Ephesus (p. 1, ch. 26): ‘We are made partakers of the body and blood of Christ, not as taking common flesh, nor as of a holy man united to the Word in dignity, but the truly life-giving flesh of the Word Himself’” (Summa theologiae III, q. 76, a. 1, ad 1). And the Council of Trent taught: “under the species of bread and wine is the divinity, on account of the admirable hypostatical union thereof with His body and soul” (sess. 13, ch. 3).