Catholic officials in Ohio bemoan harmful rhetoric against state’s immigrants

Comments by former President Donald Trump about immigrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio, insulted Haitians and those living in Springfield dealing with what has become a difficult situation, said a local Catholic official. “The Springfield community, the vast majority of migrants I’ve known, have been trying to make the situation work out for everyone,” said […]

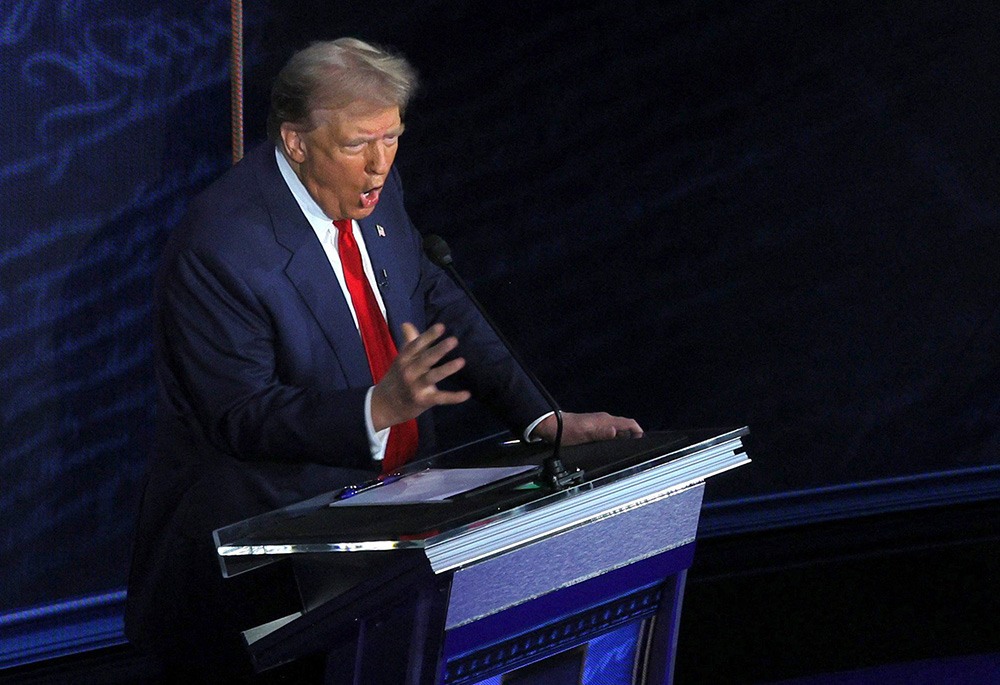

Comments by former President Donald Trump about immigrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio, insulted Haitians and those living in Springfield dealing with what has become a difficult situation, said a local Catholic official.

“The Springfield community, the vast majority of migrants I’ve known, have been trying to make the situation work out for everyone,” said Tony Stieritz, chief executive officer of Catholic Charities Southwestern Ohio.

Trump’s remarks, during the Sept. 10 debate, offered no proof, and anyone in a position to know, including the Springfield city manager, said they were pure fabrication. Television comics used the remarks as fodder and some of the estimated 67 million viewers of the debate might have thought they had stumbled upon a “Simpsons” episode, the comic cartoon set in a fictional Springfield.

But for those ministering to Haitian migrants in the Ohio city of about 60,000 there was no humor.

Two days after the debate, Springfield City Hall was closed due to bomb threats. At least two city schools were also evacuated and one school closed for the same reason. School officials at Springfield’s Catholic Central School dismissed students on the morning of Sept. 13 citing a need for caution and two local hospitals — Kettering Health Springfield and Mercy Health Springfield Regional Medical Center — were forced into lockdown due to bomb threats Sept. 14.

Catholic Charities Southwestern Ohio, a part of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, has assisted other agencies in helping Haitians in Springfield. The town is a Rust Belt industrial city, once with a population of about 80,000 which has declined in recent decades. An estimated 15,000 Haitians have arrived in recent years, many of them with protected status, granted because they are fleeing violence in their homeland. Many are legally entitled to work.

Catholic Charities has provided job placement services, English classes and food assistance, helping to aid the influx to the small city but more federal assistance is needed, said Stieritz.

“The federal government had no plan,” Stieritz told the National Catholic Reporter. The Haitian population grew over the past five years due to the informal network of Haitian refugees across the U.S. Springfield was attractive because it offered job opportunities as factory work has picked up in the region and because the area features relatively low rents.

Archbishop Dennis M. Schnurr of Cincinnati defended the work of Catholic Charities in a statement issued in March this year after the agency came under attack for its work with immigrants.

“Through our parishes, schools, and social services agencies in which migrants find themselves, the Church provides an opportunity for us to leave behind political agendas and offer the goodness of basic human interactions inspired by the faith and charity which come from God. Any of the thousands of volunteers and supporters who help make our humanitarian work possible can attest to the great gift this has provided for their own faith journeys and our communities. Working with migrants and refugees is a wonderful way to put our Catholic faith into action, just as is serving any other person in need,” wrote Schnurr.

Stieritz emphasized the cooperation that Springfielders, particularly those in the Catholic community, have offered Haitian immigrants. Mass is offered in Creole at St. Raphael’s Church, celebrated with the help of a Haitian priest who drives in from Columbus, about an hour’s drive, each weekend. He also cited the volunteer work of the St. Vincent de Paul Society.

The spate of publicity “has filled me with a lot of sorrow,” said Jillian Foster, regional director of Catholic Social Action for the archdiocese. She is a native of Ohio who served three-and-a half years as a Maryknoll lay missionary in Haiti, where she worked in a nursing home, tree nursery and served in child protection, supporting children in poverty who are sent out of their homes to become servants for wealthier Haitians, a system ripe with exploitation.

In Haiti, she saw up close the pressures of an unstable government and gang violence which makes it impossible for those in the diaspora in the United States to return. Kidnappings and killings are too common, she said, and most Haitians have been directly victimized by the violence or know someone who has.

She worries that Haitians in Springfield might again be feeling fear. “They want to learn and to work,” she said. “But a lot might be hesitant to leave their homes.”

Stieritz said the publicity generated by Trump’s rhetoric has aggravated the situation.

“A lot of hatred has been generated when the issue has been thrown into the political sphere. None of it reflects the values of our faith,” he said.

The city’s mayor, Rob Rue, pleaded with political candidates Sept. 12 to “pay attention to what their words are doing to cities like ours,” adding: “We need help, not hate.”

Similarly, Foster noted that the spotlight on Springfield largely fails to credit recent Haitian immigrants and longtime Springfield residents who want to live peacefully together.

“I know there are a lot of good people in the Haitian community and in Springfield. I hope people see that. We’re the Catholic Church. We want to embrace everyone in our community,” she said.