China bans online evangelization and ‘foreign collusion’ by clerics

Chinese authorities have issued new rules governing the online conduct of religious leaders in the country, banning unauthorized streaming of liturgies, children’s catechesis, and “collusion with overseas forces” through any online activity.

Credit: Alamy.

The Code of Conduct for Religious Teachers and Personnel, issued by the State Administration of Religious Affairs on an unspecified date, was published by Chinese state media on Sept. 15.

The code, 18 articles long, also bans raising money online for religious purposes, including the construction of churches.

The new regulations follow other recent legal restrictions on religious practice on the mainland, but the new code also applies to religious leaders in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and overseas — if they “commit online acts in China.”

The full scope of the new rules remains unclear. While the norms explicitly mention activities carried out through websites and apps — including popular messaging platforms like WeChat — the wording the regulations would appear to apply to all online communications, including email.

—

The regulations, which are in force immediately, require that all “religious teachers and officials” model behavior online that demonstrates “love the motherland, support [for] the leadership of the Communist Party of China, support [for] the socialist system, [and] abide by national laws and regulations.”

Special emphasis is given in the code to the need for all religious leaders to “practice the core values of socialism, adhere to the principle of religious independence in China, adhere to the direction of the Siniseization of religion in China, actively guide religion to adapt to socialist society, and maintain religious, social, and national harmony.”

The tensions created between the Chinese government’s policy of religious independence and Sinecization of religion have created numerous issues for Catholics in China, both clerical and lay, as have standing orders in the country which prohibit minors from attending religious services and otherwise restrict the freedom of religious practice.

While government regulations have long prohibited minors from attending Mass, the new regulations announced this week ban even the religious instruction of minors online, and producing and making available materials for that purpose.

“Religious teachers shall not disseminate and instill religious ideas to minors through the Internet, induce religious belief, or organise minors to participate in religious education,” according to the new rules.

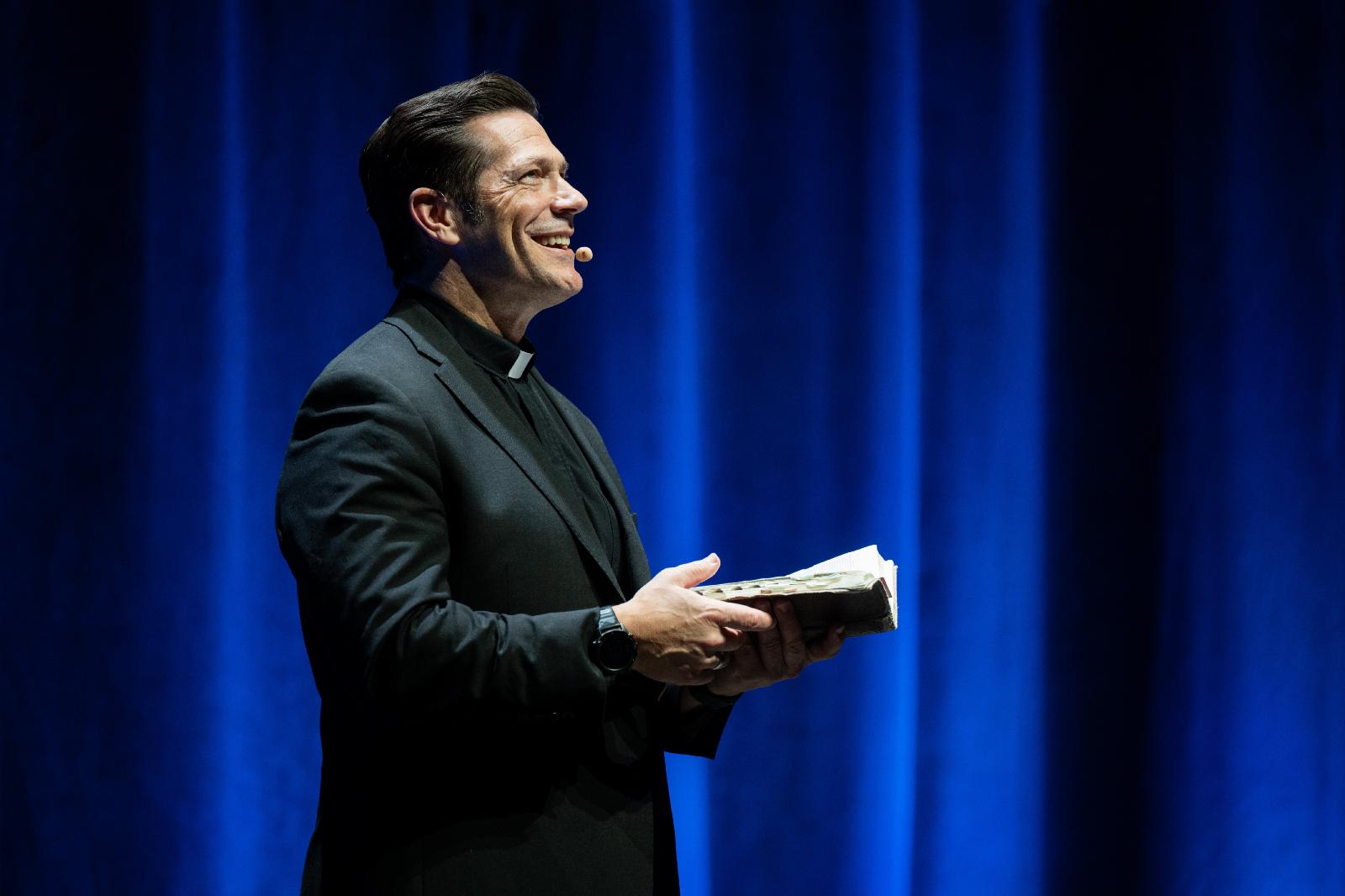

Also banned is the unauthorized “preach[ing] through online live broadcasts, short videos, online meetings,” and religious teachers and officials cannot organize or participate “in online Dharma meetings, worship, Mass and other religious activities,” nor “distribute or send religious internal information publications through the internet.”

The regulations also attempt to restrict any external religious influence, specifically stating that religious officials “shall not raise funds [online] in the name of building places for religious activities and holding religious activities.”

“Religious teachers shall not collude with overseas forces through the internet to support and participate in overseas religious infiltration activities,” according to the new rules.

“If religious teachers and officials violate this code, the religious affairs department shall order them to make corrections within a time limit; if they refuse to make corrections, the religious affairs department shall, together with the network information department, the competent telecommunications department, the public security organs, the national security organs, etc., shall punish them in accordance with the provisions of relevant laws and administrative regulations,” the code states.

The provisions of the new regulations are specifically extended to apply to Macau and Hong Kong, “special administrative regions” of China subject to separate legal systems and laws, and to Taiwan — an independent nation recognized by the Holy See over which China claims sovereignty — as well as to “foreign religious teachers who commit online acts in China.”

Reacting to the regulations, clerics in China told The Pillar that the new code was a “natural development of the Sinicization policy.”

“Religion is fine, so long as it is under the control of the state,” said one mainland cleric.

“It’s possible that these [rules] are not even primarily aimed at [Catholics],” he said, but rather primarily intended to crack down on other religions and sects like Buddhism and the Falun Gong, and corrupt local officials soliciting overseas money,” he said. “But it will still be easy for us to get killed in the crossfire.”

Another senior Chinese cleric told The Pillar that the regulations could be applied in a way which criminalizes ordinary episcopal communication with Rome.

“If you are a mainland bishop and you have any kind of ordinary communication with the Vatican which acknowledges Rome’s jurisdiction on ecclesiastical affairs, if you do it by email you could be found guilty of ‘foreign collusion,’” he said. “If any cleric was caught having anything to do with a missionary, that’s ‘infiltration.’ As always with these regulations, the aim is to criminalize anything from outside China.”

“We’re getting to the point where ordinary expressions of communion could be a national security breach,” the cleric warned.

—

The new regulations follow other religious restrictions enacted by the Communist authorities this year aimed at preventing foreign influence on religious practice on the mainland.

In April, new laws were announced banning foreign nationals from common worship with Chinese citizens, and requiring all visitors to affirm the national independence of Chinese Churches and faith communities.

The rules were branded a “pretext for arrest” by local clerics.

Clerics on both the mainland and Hong Kong have warned for years that Beijing has been bringing stricter regulations of religious practice under the guise of “national security,” and several high-profile arrests and prosecutions of Catholics in the Special Administrative Region have been undertaken on national security grounds, including Hong Kong’s former bishop Cardinal Joseph Zen.

At the same time that China has been increasing restrictions on mainland religious practice, it has approved successive renewals of the Provisional Agreement with the Vatican on the appointment of Catholic bishops for mainland dioceses, first agreed in 2018.

Despite the agreement, many underground priests, and some bishops, have refused to register with the CPCA, citing the requirement that they acknowledge Communist Party authority over the Church and its teachings.

The Vatican’s Secretariat of State issued unsigned guidance in 2019, stating that “the Holy See understands and respects the choice of those who, in conscience, decide that they are unable to register under the current conditions.” Bishops and priests who refuse to register have been subject to systematic harassment, arrests and detention.

Speaking at the time of the Provisional Agreement’s first renewal in 2020, Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin said that the agreement was intended “to help the local Churches to enjoy conditions of greater freedom, autonomy and organization, so that they can dedicate themselves to the mission of proclaiming the Gospel and contributing to the integral development of the person and society.”

At the time of the deal’s first renewal, Parolin was asked about the persecution of Christians in China and responded “But what persecutions?”

Since the agreement was first made, state authorities have also, on several occasions, moved to appoint bishops unilaterally, without securing papal approval or in some cases even informing Rome. Beijing has also, on several occasions, moved to suppress and create dioceses without papal approval, creating invalid mainland jurisdictions.

The Vatican-China deal was most recently renewed in October of 2024 for a period of four years, however senior Vatican diplomats including Cardinal Parolin have in recent months taken to making more guarded and critical appraisals of the agreement’s successes and failures.

In January, Parolin acknowledged the agreement was “progressing slowly—sometimes even taking a step backwards” and “not always successful” with its two main goals: ensuring that all Chinese bishops are in formal communion with the pope and “ensuring some degree of normalization” for the daily life of the local Church.