From Architecture to Contraception: A Journey to Paris

The mercy He gives us, one of many mercies, is that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

In the architecture of traditional Catholicism, you can contemplate God; in its liturgy you can encounter and receive Him. But in the architecture and liturgy of modernism, this is hardly possible. God may be present, but “contemplation” of Him is outdated, and encounter with Him is conditioned by the emotions conjured by strumming guitars.

As a fifteen-year old I saw this contrast on a trip to Paris with my father. I encountered two forms of architecture—one quasi-medieval, the other decidedly modern—and if the resulting spiritual implications have taken some years to develop, what I can now say is this: there exists in the Church today a contraceptive mentality whose influence extends much further than the marriage bed. The Contraceptive Church does not know beauty, common-sense, or sanity, and it does not want to see these things birthed, let alone nursed at the bosom of Mother Church and her traditions.

I should mention that this trip to Paris, which also included some days in Italy, was a turning point in my appreciation of the traditional Mass, quite possibly because before this I did not have much exposure to it in its fullness. Now I was able to see it in its true environment—celebrated by the monks in the quondam basilica of Norcia, or at Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini (the FSSP church in Rome), or in Paris at Saint-Eugène Sainte-Cécile.

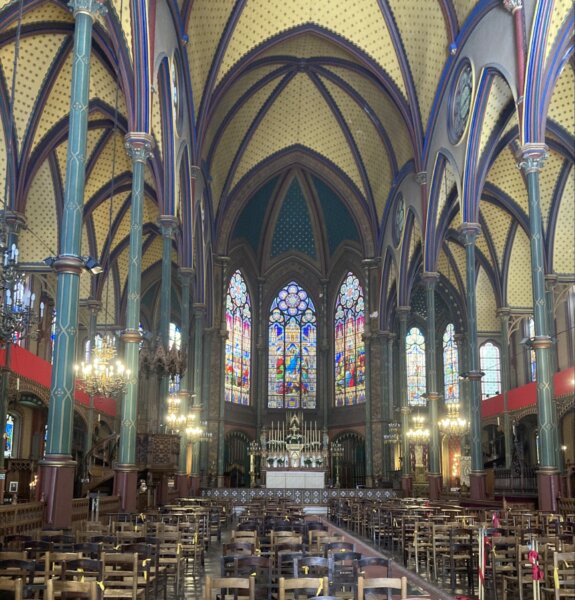

Saint-Eugène—one of the main places where the TLM is celebrated in Paris—is a church built in the Gothic revival from around the turn of the century, painted in an art-nouveau style. Because of this, its interior is rich with striped pillars and gold leaf. That might sound garish, but since the Gothic revival style tended to emphasize what they romantically assumed was the gloomy and dark ambiance of medieval architecture (incorrectly, as was discovered later), the church is at once brightly painted and poorly lit, creating a soft atmosphere of reds and golds.

Saint-Eugène-Sainte-Cécile

I wrote the following in my journal:

We went to Mass at Saint-Eugène… The silence was broken frequently by rowdy teenagers outside in front of the church (they were not being distracting or rude on purpose, just oblivious). As Consecration drew near, I could not help but think of them as representing the evil voices of the world. “Hoc est enim Corpus Meum.” As the priest elevated the host a new cry broke out, uncannily like an ugly desecration of the Host… After consecration the organist improvised a slow majestic piece with many low notes. It was as if some of the power of the Mass was made audible… All around me people knelt in prayer as the priest continued with the consecration of the wine, bowing, crossing the offering many times and genuflecting to adore Christ come to earth. The tinkle of the bells sounded throughout the church for the second time, and the organ still rumbled on. [The French have a special indult to play and/or sing immediately following consecration.] The people knelt and the pillars streaked to the lofty vaults, covered in stars. “Per omnia saecula saeculorum.” The sacrificial victim giving itself to us for ever and ever and ever. Outside the church yells and raucous laughter could be heard… “Sed libera nos a malo.”

When we visited Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on the other hand, the experience was a little different. We did not go to Mass there, but explored its architecture. It is an impressive Gothic church, built in the 12th century, and combining, as only the Gothic can do so well, a beautiful intimacy with an impressive impersonality.

Saint-Germain-des-Prés

As we walked around it and came to the apse, we found a jarring intrusion in the form of some “new” stained glass windows. They were meant to convey either the seven sacraments or the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit; I can’t remember which, since neither is conveyed well with multicolored abstract swirls. Well, I can live with that, if I sort of unfocus my eyes from them onto the column over there and think more about the overall shape of things.

“Merely to walk into a church in reverent awareness that we are entering the house of the Most High, and in a special manner into his presence, may be ‘to walk before the Lord,’” writes Romano Guardini in his little book of liturgical symbolism, Sacred Signs.

Before leaving, we wanted to visit the Blessed Sacrament chapel. We stumbled upon it through a door to a little room, expecting some modest and dark stone space. Instead, we found a bare stone chapel, having for a tabernacle a bare white box protruding from a bare wall. The chapel itself seemed ancient but now stripped of all decoration. Beside the white cube was a small light. With a little additional work it could have become the “white room” for a NASA space-ship assembly! Or maybe its designers had envisioned it as a walk-in freezer for keeping perishable refreshments needed at church events.

Chapel of Saint Symphorien

Perhaps someone wishing to refute me will say that this sacrament hall was supposed to be spacious and light, as the pure in heart are supposed to be. Yet “pure of heart” does not mean “cubic and colorless of heart.” I would rather purity be associated with the spare, unadorned Romanesque style, which nonetheless maximizes harmony of shape through its simple curved lines. It is ironic that a journey to Paris, the fertile bosom of Europe’s eldest daughter, should have led to such a contracepted space. It was not a pure space but a sterile space. It had taken the heart of a venerable church and bleached it, placing the Seed that fell to the ground for the life of the world in a laboratory-like locker.

Looking back on his conversion to Catholicism in 1960, the philosopher and author John Senior wrote: “To my astonishment, as I mounted up the gangplank to the Ark, I was all but trampled by a hoard of crazy Catholics rushing to embrace in the name of ‘Renewal’ the very horror I was leaving” (from “The Last Epistle,” in the posthumously published Senior anthology The Remnants). And he added: “The Irish keep the cottages and crosses at the crossroads for the tourist trade but sing catchy liturgies in plastic Gothic chapels as they practice divorce, contraception and abortion like the rest of ruined Christendom. The body is beautiful still; the mind is best described by Joyce.”

In our own lives we must say an uninhibited and unreserved “Yes!” to beauty. Pope Francis speaks of the “God of Surprises” and the “Church of Mercy.” We know by now that the surprises and mercy Pope Francis offers are not the surprises and mercy Christians want or need. The surprise that God gives us is beauty and life. The mercy He gives us, one of many mercies, is that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel: we have a tradition and a Magisterium to follow. Senior writes in the article already quoted: “It must go without saying that the Catechism of Trent and the Roman liturgy must be the norms of doctrine and worship. The phenomenologist conception of a pilgrim Church becoming Christ is Catholic Gnosticism, not the Catholic faith semper, ubique idem.”

We must also say “No!” to the Contraceptive Church. Beauty, common sense, and even sanity will never germinate if placed in the pseudo-rationalist and relativistic womb of situational ethics and Modernist deconstruction. More than babies can be contracepted: if we are saying “No!” to prelates who try to convince us that sterile wombs (or worse) are a true expression of human love, let us also say “No!” to them when they try to convince us that sterile churches are an expression of Divine Love. They know better–they should know better–than the soccer-playing boys outside of Saint-Eugène.

Ought we to compare outrages? To desecrate the female holy of holies with enforced barrenness is a crime against the God of mercy and surprises that parallels only too well the placement of the Bread of Life in a rubix cube. I can say this at least: from architecture to contraceptives, the mentality that will enable us to be “delivered from evil” and become partakers of the Holy Body of Christ is the mentality that built churches like Saint-Eugène and Saint-Germain–not the one that white-washed them.