Holy Week and Easter: The Fact of Our Redemption

Holy Week and Easter bring with them liturgies of great beauty and solemnity suitable to the momentous significance of the events they recall. That significance is of course redemption. And for assistance in explaining it, I turn to three highly qualified commentators—Blaise Pascal, St. John Henry Newman, and St. Augustine. Start with Pascal. “There are […]

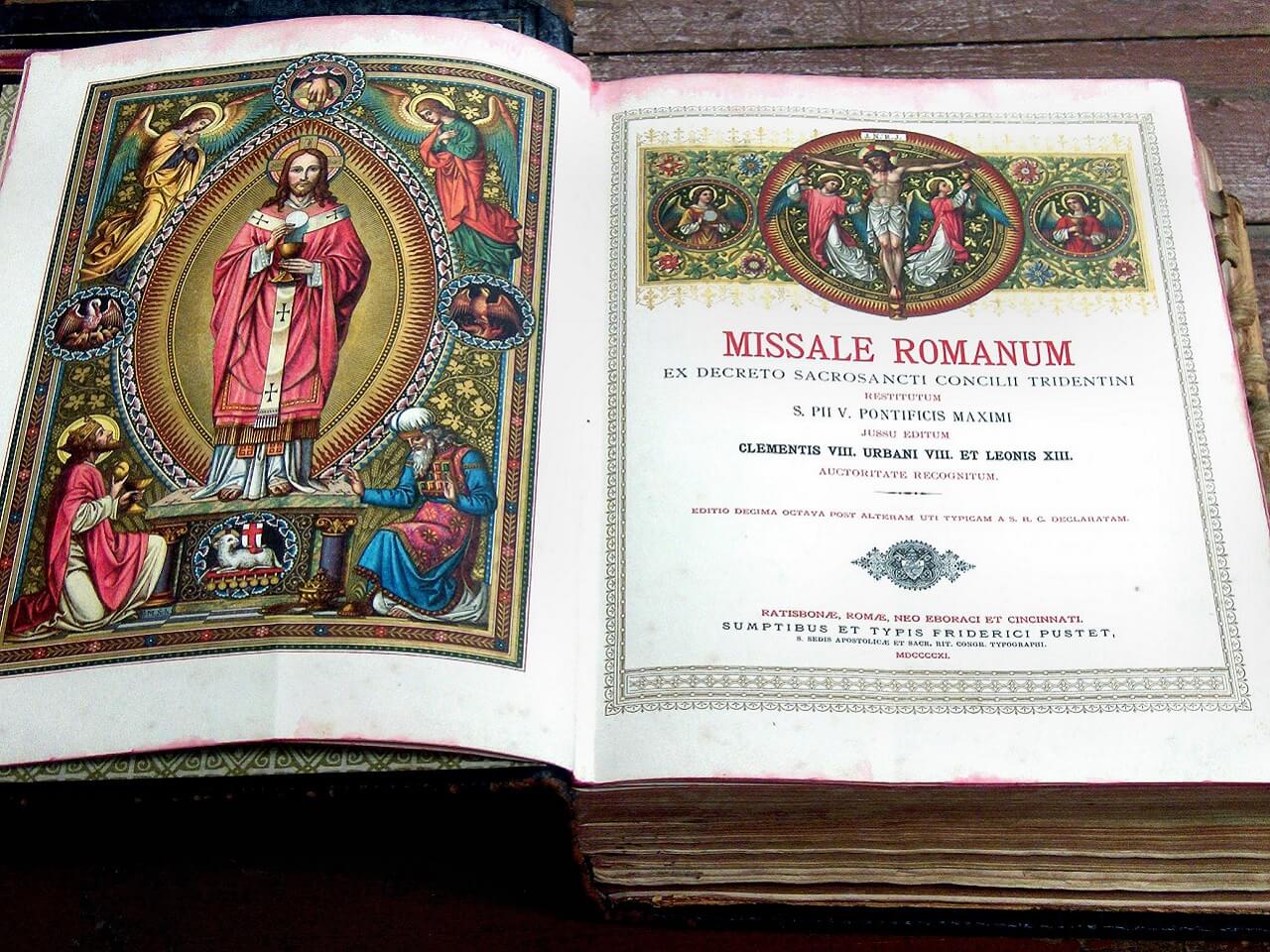

Holy Week and Easter bring with them liturgies of great beauty and solemnity suitable to the momentous significance of the events they recall. That significance is of course redemption. And for assistance in explaining it, I turn to three highly qualified commentators—Blaise Pascal, St. John Henry Newman, and St. Augustine.

Start with Pascal. “There are two truths of faith equally certain,” says this 17th century French mathematical genius and religious philosopher. “One is that man, in the state of creation or in that of grace, is raised above all nature, made like unto God and sharing in his divinity. The other, that in the state of corruption and sin he is fallen from this state and made like unto the beasts.”

In this situation, Pascal reasons, there is a pressing need for someone to restore humankind’s relationship with God, severed by that mysterious fall whose consequences are all too apparent in human history and human hearts. But who can do that? The answer, Pascal writes, is “Jesus Christ the Redeemer”—he who “ransomed all those who were willing to come to him.”

This takes us deeply into Holy Week. What we recall and re-enact on Good Friday is Jesus’ supreme redemptive act—that perfect acceptance of the Father’s will through which he brought his vocation as redeemer to fulfillment by suffering crucifixion and death for us.

Newman explains the essential role in redemption of the human nature Christ shares with us: “God took our nature on him that in him it might do and suffer what in itself was impossible to it….When human nature died in him on the cross, that death was a new creation. In him it satisfied its old and heavy debt; for the presence of his divinity gave it transcendent merit.”

Remarking that many of his Victorian contemporaries don’t believe all this, Newman imagines them saying: ”We see no necessity for so marvelous a remedy; we refuse to admit a course of doctrine so utterly unlike anything which the face of this world tells us of.” And now? Do many of our contemporaries disbelieve because, having thought deeply about redemption, they find it incredible or because they hardly think about it at all?

But Easter celebrates a fact—redemption—with Christ’s resurrection as God’s seal confirming it. By Jesus’ supreme act of self-sacrifice, our ransom has been paid, with splendid consequences. And here I turn to an Easter sermon by Saint Augustine, preached early in the 5th century to his faithful in the North African city of Hippo:

“All these evils…which we are aware of in the body have been brought on by sin, they didn’t come about through our natural condition. From the very beginning, after all, through the man who sinned we have received this evil inheritance from our father the sinner.

“But there came to us another inheritance, that of the man who took on our inheritance and promised us his own. We were in death’s possession by guilt; he took death to himself without guilt. He was put to death and so tore up the debtors’ bills. So, all of you, let your minds be full of faith in the resurrection. What Christians are promised is not only everything that the scriptures proclaim has been done in Christ, but also what is going to be done in him.”

Forget chocolate bunnies and colored eggs for a moment. Redemption is about something immeasurably greater. And with that glad thought I wish you a blessed Holy Week and joy-filled Easter.

Photo by Bruno van der Kraan on Unsplash