Is the information age a ‘Crisis of Narration’? This book says yes

The Crisis of Narration Byung-Chul Han 100 pages; Polity $16.95 We live, we often hear, in a world full of information, deracinated data stamping out all the humanity from our lives. The Catholic Korean-born German philosopher Byung-chul Han, recently hailed as an internet sensation, offers one such account in The Crisis of Narration. The slim volume of […]

The Crisis of Narration

Byung-Chul Han

100 pages; Polity

$16.95

We live, we often hear, in a world full of information, deracinated data stamping out all the humanity from our lives. The Catholic Korean-born German philosopher Byung-chul Han, recently hailed as an internet sensation, offers one such account in The Crisis of Narration. The slim volume of essays suggests that the real harm of information is that it has displaced a more essential practice of human life: narration.

This argument, Han recognizes, might sound odd, because we seem to hear about narrative all the time. Corporations hire writers for data storytelling. Cognitive behavioral therapists and self-help gurus invite patients to investigate the stories they tell themselves. News media and elected officials construct political narratives to keep supporters in their orbit.

But The Crisis of Narration suggests that these are narratives in name only; they don’t have the world-making power of myth or religious ritual. True narration, for Han, “unites things and events, even trifling, insignificant or incidental things, into a story.” In other words, it infuses the world around us with meaning.

We don’t live in that kind of world, the book argues; we live in a world where disjointed, inhuman information saturates social media platforms, smart devices and news media. In contrast to narrative, which enters into human experience, information is “unavailable,” “disenchanting,” “fragmenting” and “mechanical.”

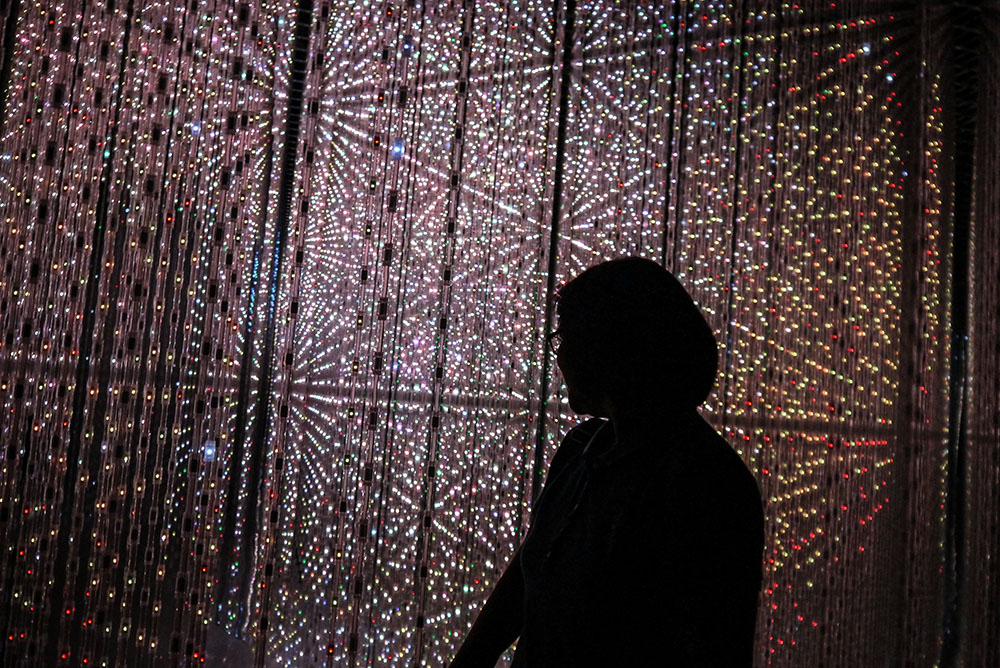

Social media is Han’s most frequent target. Though platforms like Instagram brand their content as “Stories,” they contain only “information adorned with images — information that is briefly registered and then disappears.”

Advertisement

The Crisis of Narration is written in the same style as Han’s previous books (most famously Psychopolitics and The Burnout Society): aphoristic, terse, more like a German Romantic philosopher than a contemporary academic. Few sentences run long; almost no paragraphs take up more than a few lines.

The benefit is that Han’s writing is fairly readable. The downside is that there’s little nuance to his ideas, which becomes increasingly clear as the book progresses. Each chapter spends about half its length liberally quoting a small cadre of 20th-century existentialist philosophers, then drawing tenuous connections to the present world.

The result is less a critical dialogue and more a regurgitation. Han cites Martin Heidegger, peppers in a paragraph about smartphones, then wraps things up.

It isn’t necessarily a problem to draw on decades-old thinkers (many of Han’s touchstones, like Walter Benjamin, offer prescient accounts of contemporary society). But Han is an abler reader of interwar philosophy than he is of modern digital life. As he attempts to integrate 20th-century philosophy into an account of the present, critiques become half-baked screeds: Snapchat is fleeting; Facebook and Instagram are disingenuous; selfies are shallow; children search for “digital Easter Eggs” instead of wonderment; photographs cut us off from the world.

There might be something worth exploring in each of these arguments, but Han eschews evidence and nuance in favor of superficial clichés. Nowhere is this more evident than his blithe assertion that humans have transformed from homo sapiens into “phono sapiens.” His arguments are only slightly more polished versions of underinformed technophobia.

An especially curious element of Han’s writing in The Crisis of Narration is his romanticized vision of Christianity, particularly medieval Catholicism. For Han, the Middle Ages represent a moment in which the world was saturated with narrative meaning and everything, every “nook and cranny of life,” was given significance by Christian ritual. Truth was not “contingent, exchangeable, and modifiable” as it supposedly is now, because religion (he says) “narrates contingency away.”

“An outbreak of the plague was not pure, simple information,” he argues elsewhere. “It was integrated into the Christian narrative of sin.”

Han has clarified that he does not believe in “reactivating” the “Christian narrative,” since it has “lost power” in the Western world. But it’s difficult to read his antimodern jeremiad outside the context of resurgent traditionalism. To be sure, Han is citing Jean-Paul Sartre, not G.K. Chesterton. But the core of his argument is that the (so-called) premodern faith in narrative has decayed into a superficial culture that lacks the “rituals” that might give life meaning. We live, he insists, in a depraved world.

In this postlapsarian angst, Han holds tight to the idea that there were halcyon days where people used religion to make meaning instead of tweeting. But this account of premodern Christianity is questionable.

Certainly, Christianity was a powerful cultural force. But much writing of the period, like the ribald and often anticlerical humor of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales or the profound anxiety of William Langland’s Piers Plowman, reflect that the Christian narrative never really “narrated contingency away.” Uncertainty has always existed — Christian doubt is as old as Christianity itself.

These kinds of activities represent the heart of Christian practice: finding God in the world that we’ve found ourselves in.

On the flipside, Han’s romantic approach to narrative prevents him from seeing how modern narrative practices, especially Christian ones, are engaging with the world of information.

An Instagram image might seem fragmentary, but the act of sharing can itself be a meaning-making ritual — as when a candid selfie of a sleep-deprived mother can become a site for sharing honest conversations about parenting and cultivating the beloved community virtually.

A Twitter timeline might seem to render world news as rarefied facts, but, as in the case of the obscene violence of the invasion of Gaza, these facts can also be transmuted into stories, holy icons and rituals.

A scroll of random video reels might seem disjointed, but reflective prayer — the act of narrativizing one’s experiences before God — can illuminate the Holy Spirit’s movements through the touching personal humor or novel knowledge or immense frustrations of social media.

These kinds of activities represent the heart of Christian practice: finding God in the world that we’ve found ourselves in. It’s true, information poses new challenges. We need thoughtful discernment and the courage to find new ways of narrativizing the human relationship with God. But even in the world of information, humans continue to narrate graced meaning.

Han’s argument might be compelling if you already believe everything he says before you start reading the book. But his reactionary logic misses the vibrant narrative activity that continues to pulse through our digital lives.