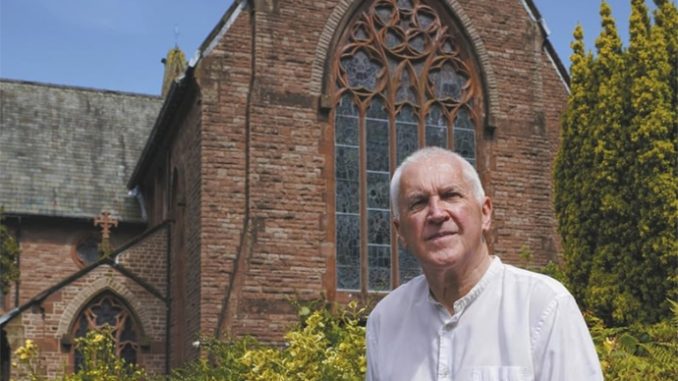

Keeping the Faith with Fr. Aidan Nichols

(Image: Gracewing / www.gracewing.co.uk/page475.html) In several ways, Fr. Aidan’s Nichols’ Apologia is a keeping faith with positions he has held for many years. He remains full of hope about the conversion of Anglo-Catholics, even though...

In several ways, Fr. Aidan’s Nichols’ Apologia is a keeping faith with positions he has held for many years. He remains full of hope about the conversion of Anglo-Catholics, even though he laments the unreadiness of the Church to admit more of what he regards as good and faithful Anglican tradition. He remains fond of the traditional French, even though he realizes that his Thomism might not be entirely theirs. He remains full of hope about the ability of the Church to reclaim her ancient essence.

“All who truly love the bridal Church have the capacity, in their time, place, situation, to awaken the sleeping beauty with a kiss,” he says. “For this love to eventuate one thing is necessary. We must refind something lying beyond any conceivable ecclesiastical structure or procedure and beyond, too, whatever panaceas are currently on offer for the earthly condition. We must rediscover something far greater: the essential supernaturality of the faith of the Church.”

On these matters and his unusually meditative youth, Fr. Nichols is fascinating. If John Henry Newman was insistent that one inalienable aspect of English Christianity was its appreciation of the Providential, nearly every chapter in this just, thoughtful, ebullient book confirms how much God’s Providence has meant to Fr. Nichols. It sustained him in an early home life that was the reverse of jolly, his mother dying of cancer when he was all but eight and his much older father succumbing to dementia before the author had left his teens. It fortified him for his life of faithful, scholarly itineracy. Indeed, he pointedly quotes the words with which Ken Platt (1921-98) the Blackpool comedian opened all his skits, “Allo, I’ll take me coat off but I’m not stoppin’.”

It certainly guided him, via a trip to Geneva when he was thirteen, to a recognition of the personal God. As he relates:

I went into the Russian church (a triumph—I later learned—of the revived Muscovite style, built by the Grand Duchess Anna Feodorovna, the sister-in-law of Alexander I), and gazed at the iconostasis. With the speed of a moment I took in the implications of the icons of Christ and his Mother and their veneration by a member of the faithful, who made a profound bow, then planted a kiss and by way of continued homage lit a taper. This was the incarnate Lord, the personal God made human in the Blessed Virgin—a notion that no amount of compulsory church attendance at school had managed to instill.

A Roman Catholic acquaintance at his Blackpool school reinforced his sense of the coherence and richness of the Roman Church. As he writes, “This was the start of my ‘path to Rome’. I was influenced by impressions of church interiors and devout practices in the Catholic cantons of Switzerland, but the decisive question was: By what authority? I sought a teaching Church which knew its own mandate and its own mind—something that could not be said of Anglicanism however reassuring its cultural face.”

Since Fr. Nichols’ life has been devoted to expounding various theological aspects of the “teaching Church,” there is much in the reminiscences about his own prolific, wide-ranging, scholarly work.

Yet there is one big surprise in the book and that is in his reaction to the fallout from his controversial stand against the current pope’s deviations from magisterial Church teachings. In light of the doctrinal errors in which Pope Francis has persisted since Fr. Nichols’s co-signed letters questioning the doctrinal acceptability, first, of Amoris Laetetia and, secondly, of the Abhu Dhabi Declaration, it is striking how completely the author eschews any crowing. Certainly, his concern regarding these and other papal aberrations have been vindicated, even though few of his critics have had the grace to admit as much. Instead, Fr. Nichols contents himself with pointing out that the calamitous ambiguity that both matters caused continues unclarified. The imperturbable wit in him also accepts that his travails, in an age of so much doctrinal confusion, might have been unavoidable. “If you want a quiet life, do not get involved with God, Gospel, and Church,” he says at one point.

One signal benefit of the autobiography’s revisiting the controversial letters is to show how much more prescient than merely controversial they now seem. “The deafening silence that ensued was disorienting, not to say subversive,” he admits in one passage. Yet he also reveals that he:

was not among those signatories who thought the letters simply set down markers for the future. No doubt naively, I expected that a substantial proportion of the cardinals (the first letter) or the bishops (the second) would take a stand on the chief issues involved. In that eventuality, it might quite reasonably be expected that the pope would reconsider his position (in either of the possible senses to be given to that phrase). The second of the two letters achieved a great deal of publicity, since it raised the issue of a pope who, by negligence or misdirection, strays into doctrinal error (heresy): a possibility widely canvassed by theologians of the Renaissance and the Catholic Reformation, acknowledged at the First Vatican Council, and discussed by canonists of the period which preceded its later twentieth-century successor. If, as a schoolboy of seventeen, I had been required to abjure heresy, why should not a pope, confronted with his own at best ambiguous statements, be equally required to affirm orthodoxy? It is far more important that the Petrine office-holder, who embodies in his own person the claim to doctrinal purity of the sancta romana ecclesia, be absolutely scrupulous in such matters than it is for any mere practicing theologian (say, for instance, Balthasar). Naturally, no Catholic could possibly enjoy raising this issue (unless they are ‘Sedevacantists’). So the number of initial signatories to the second letter was predictably fewer than with the first, and the names of those who had been approached (and had agreed) correspondingly more prominent in the press. The language used in the second letter was certainly strong. But the seriousness of the situation called for a kind of description that eschews diplomatic formulae of an ambiguous kind. The gains in clarity made by the two last popes were at stake. Not that those popes had themselves proposed doctrinal novelties. The ‘gains in clarity’ they achieved were inroads on the relativistic fog that has settled on the maze of modern life.

Of course, with the current pope’s ratification of his doctrinal head’s Fiducia Supplicans, the “relativistic fog” against which Fr. Nichols inveighs has only deepened. Any accurate history of the Francis papacy would have to begin by evoking the ubiquity of fog that opens Dickens’ Bleak House (1853): “Fog everywhere… Fog creeping… Fog lying out in the yards… fog drooping… fog in the eyes and throats… fog in the stem and bowl of afternoon pipes…”

If few even faithful Catholics risk incurring the backlash that met Fr. Nichols’ defense of the integrity of magisterial Church teaching, their silence cannot change the stakes that the memoirist so indisputably sets out in his Apologia. “The reiteration by St John Paul II of classic Christian teaching on the moral life, the conjugal life, and the sacramental life,” he writes, “as found in, respectively, Veritatis splendor in 1993, Familiaris consortio in 1981, and, between those dates, the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, could hardly be expected to survive the triumph of a successor document on the same topics—marriage and the family, the character of moral norms, the relation between the Commandments and sanctifying grace, if the new document—Amoris laetitia—be taken to ratify the very theological dissent the Johanno-Pauline texts were intended to unchurch.”

Here, indeed, is the apparent repudiation of magisterial teaching that the Francis papacy has been allowed to achieve. Yet, where courageous but easily marginalized prelates and laity are its only critics, such repudiation proceeds apace, especially in circumstances where “changes to the personnel and policy of the John Paul II Institute for Marriage and the Family, and the Pontifical Academy for Life, as well as the general tenor of such events as the Pontifical Gregorian University conference ‘Moral Theology and Amoris Laetitia,’ held in the spring of 2022, confirm the unsettling of the moral magisterium not only of the Polish pope, so recently canonized, but of the wider precedent tradition of the Church.”

And, as Fr. Nichols dryly observes, the lack of any effective challenges to the papal vagaries has long bred a kind of authoritarian intolerance in the pope and his friends. The example Fr. Nichols adduces has an almost comical ruthlessness. “When the finest living Italian moral theologian, Livio Melina, sought to argue that Amoris laetitia might conceivably be interpreted in such a way as to leave untouched the fundamental ethical doctrine of the philosopher-pope, he found himself summarily removed from his headship of the very pontifical institute which bears John Paul II’s name.”

Another well-meaning, indeed, irenical figure, Bishop Jean Lafitte, author of the excellent, if laboriously entitled Christ: The Destiny of the Human Person: A Journey into Filial Anthropology (Gracewing) was recently removed from his post as Prelate of the Sovereign Order of Malta for detailing what had been the orthodox zest of the Pontifical Academy of Life before Pope Francis and his friends set about demolishing it. So much for the current’s pope’s vaunted delight in dialogue.

A good example of Fr. Nichols’ playful wit can be found in his portrayal of the response of the English Dominicans to his papal criticism. Despite their never being known themselves for what the author nicely calls “ultra-papalism,” they were not over-eager to come to their fellow Dominican’s defense. Why?

Their journal, New Blackfriars, had published articles critical of Paul VI’s support, in the encyclical Humanae vitae, for the traditional blanket prohibition (no pun intended) on artificial contraception. Under John Paul II an entire issue had been devoted to an attack on the doctrinal ‘restoration’ (really, rectification, the French would say redressement) mounted by the then Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under its prefect, Joseph Ratzinger. So a surge of resentment at criticism of a pope seemed somewhat out of corporate character. It was, however, true that, in regard to Blackfriars, Oxford, a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford, and hence a prominent public organization in English Catholicism, to shake off a reputation for left-wing dissent only in order to gain one for its right-wing equivalent was not, in public relations terms, especially advantageous.

Clearly, when Aidan Nichols, OP found himself odd man out there was little rallying round from his fellow English Dominicans.

That the punishment doled out to Fr. Nicholas for sticking his neck out for the dogmatic principle should have been exile to Jamaica gives his heroic testimony a farcical twist. In the Church of Jorge Bergoglio, there is a kind of poetic justice that one of our best theologians should be sent to a place where there are no books and the local Catholics feel obliged to ape their more popular “Evangelical and Pentecostal competitors” by mingling “their worship with African folklore”—“storytelling” always trumping “doctrinal instruction.” Here, predictably enough, in the midst of fairly raucous liturgical services, Fr. Nichols’ affinity for the “teaching Church” would find neither echo nor comprehension.

Yet the faithful humility that Fr. Nichols has exhibited since he decided in good faith to sign the two letters that set off such controversy is summed up by something he says at the very end of his admirable memoir. “I certainly did not want to be an occasion of serious division… where there was a spectrum of opinion on delicate issues.”

Apologia: A Memoir

By Fr. Aidan Nichols

Gracewing, 2023

Paperback, 150 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.