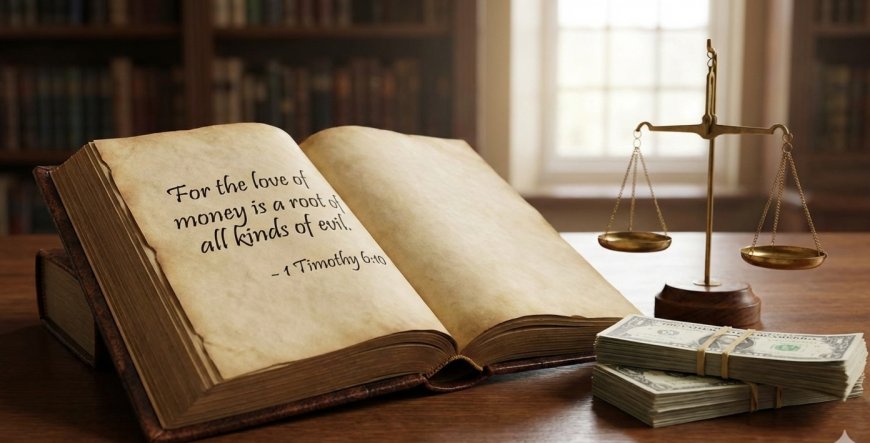

Money is A Moral Question

Money is not neutral. It never has been.

January 24, 2026, Bangkok

I write this not as an economist first, nor as a historian, but as a believer who has spent years sitting with Scripture, with the Church’s social teaching, and with the quiet suffering of ordinary people trying to survive an economy that no longer sees them.

The Bible never treats money as a technical matter. It treats it as a spiritual one. From Genesis to the Gospels, money appears wherever human trust begins to crack—where fear of scarcity replaces faith, where accumulation replaces communion.

That should tell us something. Money was born from human need, not from human greed. It did not enter the world as a sin. It entered as a solution.

Long before banks and markets, human communities exchanged goods through relationships. You gave because you belonged. You received because you would one day need mercy yourself. But as societies grew larger, memory could no longer hold all obligations. Trust needed a record. Value needed a sign.

Money emerged to serve the community. Yet the moment value could be separated from the face of the neighbor, it became vulnerable to manipulation. What began as a servant quietly learned how to rule.

Scripture is painfully honest about power. Kings minted coins. Empires demanded taxes. The poor were forced to earn the currency required to survive within systems they did not design.

This is why Jesus speaks so sharply about money. Not because He despised work or trade, but because He saw how money reshapes the heart. “Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” He was not offering poetry. He was diagnosing a condition.

Money trains desire. It teaches us what to love. When money becomes the primary language of society, everything else must translate itself into it—time, land, labor, even life itself. The Church calls this a distortion of the moral order.

Catholic social teaching has never condemned money outright. That would be dishonest. Markets coordinate human activity. Wages feed families. Institutions require structure.

But the Church has always insisted on something modern culture finds uncomfortable: the economy must serve the human person, not the other way around.

From Rerum Novarum to Centesimus Annus, from Caritas in Veritate to Laudato Si’, the teaching is consistent: money is morally acceptable only when ordered toward the common good. When it becomes autonomous—when profit justifies harm, when efficiency excuses exclusion—it becomes an idol. Idols always demand sacrifice, usually of the poor.

Today, we are told that the market is neutral, that outcomes are natural, that suffering is unfortunate but inevitable. This is not realism. It is abdication.

When an economy rewards speculation than labor, when it treats housing as an asset before it treats it as shelter, when debt becomes a lifelong condition rather than a temporary tool, something has gone wrong at the level of values—not policy.

Pope Francis has said it plainly: an economy that excludes is an economy that kills, not always with weapons, but with indifference.

What would happen if money stopped being the measure of all things?

This is not a call to abolish currency overnight. It is a call to recover moral imagination. Scripture reminds us that human worth precedes productivity, that the Sabbath exists to limit economic domination, that the poor reveal the face of Christ.

A society shaped by this vision would still trade, still plan, still innovate—but it would no longer pretend that price equals value.

It would remember that some things must never be for sale.

At the end of the Gospel, we are not asked how efficiently we managed resources, but whether we fed the hungry, welcomed the stranger, clothed the naked. The criteria are painfully concrete.

Money will not stand beside us at that judgment.

Our balance sheets will not speak for us.

What will matter is whether we allowed money to harden our hearts—or whether we insisted that it remain a tool, never a master.

The Church does not ask the world to abandon the economy.

She asks it to recover its soul.

Because in the Kingdom of God, no one is disposable, no life is surplus, and no human being is reducible to a number. Any economy that forgets this has already failed—no matter how profitable it appears.

By: Bro. Jimmy C. Salonoy, S.Th.B