On being alone in the presence of another

(Image: fancycrave1/Pixabay.com) Pope John Paul II often gratefully spoke of an “ecumenical gift exchange.” In that spirit, the rector of my Anglican boyhood parish, knowing of my interests in both psychology and theology, gave me books by...

Pope John Paul II often gratefully spoke of an “ecumenical gift exchange.” In that spirit, the rector of my Anglican boyhood parish, knowing of my interests in both psychology and theology, gave me books by the Catholic priest Henri Nouwen, who had recently taken up residence an hour away from us at a L’Arche home in Richmond Hill, Ontario. I profited greatly from reading Reaching Out: the Three Movements of the Spiritual Life and Out of Solitude.

In both books, Nouwen wrote memorably about the movement “from loneliness to solitude.” I estimate I read his books sometime in early 1990. By Labour Day 1991, I had left home for university, moving hundreds of kilometres to the much larger city of Ottawa where I knew nobody. A month later, I received the shattering news that my sister was dying.

That fall and winter were marked by a descent into mourning for her mixed with melancholy and loneliness. I was a full-time student at a huge university with 30,000 students, and a part-time pharmacy clerk in the busiest shopping mall in a city of nearly one million people, but I wandered around the Canadian capital as if I were on a deserted island, the psalmist’s words frequently (if a touch melodramatically, I might now observe) on my mind: “friend and neighbor you have taken away, and darkness is my one companion left” (Psa 88:18).

The darkness began unexpectedly to budge slightly the following year around mid-May when Ottawa’s merciless winter had lifted, the academic year was over, and I could get my bike out again. I knew I could not magic up friends, or return to the past no matter how intense the pangs of nostalgia were. But unconsciously I began intense work on this movement from loneliness to solitude. I’m still working on it.

Fortified by Nouwen, I was, as a psychology student, now reading such writers as the British psychiatrist Anthony Storr, author of Solitude: A Return to Self, and a little later I would read the great paediatrician and psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, whom I have never stopped learning from down to the present day. (Winnicott’s thought on these questions is well captured in a splendid new book by Christopher Bollas, Essential Aloneness: Rome Lectures on DW Winnicott, Cambridge UP, 2024). All these writers suggested that we can allow at least some of our time alone to be not a place of desolation and isolation, from which we ache to escape, but instead a rich and life-giving garden of solitude to which we go with some anticipation, perhaps even delight.

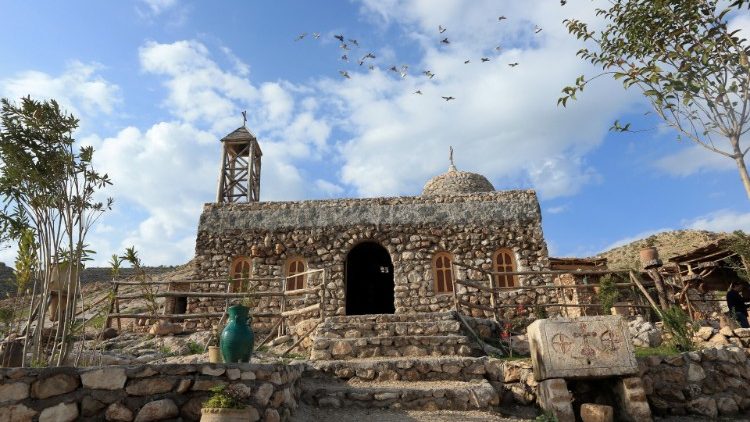

In this they echo the solitaries and monastics of Christian antiquity–figures like Mary of Egypt, Evagrius of Pontus, Simeon the Stylite, and later Benedict of Nursia, Ignatius of Loyola, and Dorothy Day.

For me the experience of enriching solitude began unexpectedly while riding my bike at night along the wonderful pathways beside the Ottawa river and Rideau canal. In the cool air of a spring evening, the lights of Parliament Hill high in the distance above me danced on the water as I rode for hours without any sort of route in a city that I had not yet begun to explore. Bit by bit, these nocturnal rides gave rise to a new sense of aliveness as loneliness seemed to be transformed into solitude. (Recent clinical research has confirmed that outdoor exercise, especially near water, can have salutary and healing effects on the mind, ameliorating some forms of depression and anxiety.)

As a practicing psychotherapist, I regularly hear about how achingly lonely some people are, especially the Catholic clergy who have been my patients, though it is certainly not limited to them. (Medicine is another intensely personal but very lonely profession.) In sessions with my lonely patients, the question is regularly on my mind: how might they move from a barren loneliness to a richer solitude?

Though the great psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichman, in the last essay of her life in 1959, called for more research on experiences of loneliness and solitude (which she called “constructive aloneness”), few have undertaken that until now: Solitude: The Science and Power of Being Alone, co-authored by Netta Weinstein, Heather Hansen, and Thuy-vy T. Nguyen (the first and third of these practicing psychologists in England while Hansen is an American science journalist) and just published by Cambridge University Press this year, is a rich, fascinating, and sometimes overly sanguine book.

I have long been aware that my question above–about moving from loneliness to solitude–is a simplistic one, and requires several qualifications. In the first place, even if we have the fattest and most satisfying fruits on the trees in our garden of solitude, we will still sometimes be starved for the company of others. Every life will have periods of unwanted loneliness; some will have experiences of solitude we crave; and most of us will probably muddle on with some mixture of both. What is the relationship between them? It is far from straightforward.

Adults today spend nearly one-third of waking life alone, and the authors further report that the number of people living alone is at an all-time high. This has led to frequent headlines for years now about an apparent epidemic of loneliness, but the data do not support so straightforward a story. Not everyone living alone is lonely, and for those who are, the situation is more complicated than “get a pet” or “find a spouse.” The authors rightly recognize that “simply spending less time alone or more time with others isn’t a ‘cure’ for loneliness.”

As Winnicott argued, aloneness is an essential part of the human condition but that does not mean that aloneness equals loneliness. For Winnicott, it is crucial to our flourishing that we learn to be comfortably alone, that is, capable of profiting from solitude without manically trying to fill the gap. Though he didn’t quite put it this way, we might say that our askesis in solitude paradoxically begins only in the presence of another. This is usually the mother or other primary caregiver who is nearby while the young child is playing alone.

Other paradoxes abound in discussions about solitude, and the three authors rightly recognize them at the outset: “it’s tough to study solitude in real time because by its very definition, people can’t be alone and talking to researchers!” That, commendably, did not deter them from undertaking an impressive number of often creatively designed studies (many undertaken during the pandemic when the whole world suddenly was plunged into strange forms of loneliness and solitude everywhere all at once) of adults around the world and their experiences of solitude, allowing them to learn that “solitude can be wonderful, even transformative.”. Interviews with those who enjoy solitude are quoted throughout the book, giving glimpses that are often both moving and inspiring.

The authors note that some people are more adept at profiting from solitude. Some are also more driven to seek it because of the work they do. For example, among “caretakers,” including “therapists, nurses, and stay-at-home parents”, “the desire for solitude, and specifically the need for private solitude, seemed more prevalent.” “Private” solitude means solitude in the absence of other people since some people can experience solitude while others are around.

This finding certainly resonates with me: I do my best metabolizing of clinical material while out for a run (once more along a river) entirely by myself. The often searing (and sometimes thrilling!) sessions I have with my patients are processed on those runs in ways that are crucial for my own health while also decluttering my mind and so protecting my ability to recreate the next day that “bare attention” (as Nina Coltart, herself heavily influenced by monasticism, put it) that my patients have a right to expect–attention stripped of my own memories and desires and distractions so that I can listen in a self-forgetting way. Solitude does that for me.

When I suggested this review to CWR’s editor Carl Olson, he made an off-hand wry comment about the book’s appearance being a bit “Oprah-ish.” In this he knew more than he realized! Frequently the book uses language I might call “covert capitalist apologetics” as when we are told that solitude can help us “improve the quality of our relationships” and is “not a shift away from others but an intentional move toward our best possible selves.” Regularly the “benefits” and “perks” of solitude are extolled, not least for workers to become more productive and resilient. There is an entire chapter “What Makes Solitude Great?” whose infelicitous wording is close to a sinister political slogan many of us hope never to hear again.

Why best–why must that be here? Why great? Why not “good enough” solitude, to use Winnicott’s famous phrase? Is there some sort of competition here? We are not told.

Other questions, the authors tell us, will require further research. For example, if some people are not interested in or capable of using solitude, are they out of luck? No: “that doesn’t mean that people who haven’t developed that capacity are out of luck. Building that ability for being alone is not like flipping a switch; it takes time” and effort. Such efforts will likely include five factors the authors found showing up again and again in the self-reports of people who felt they were “good” at solitude. These are: optimism, a growth mind-set, self-compassion, curiosity, and being present in the moment.

Once again this language (“growth mind-set”) suggests a crude utilitarianism that many Christian authors would probably find troubling. The book does briefly quote one Christian monastic, Thomas Merton, who made such a strong case for solitude these authors hasten to reassure readers we do not need to become so “extreme”.

What Merton hinted at here is more clearly seen in other theological writers who glory precisely in solitude’s lack of socioeconomic utility. I have in mind the late Dominican Herbert McCabe, who wryly observed that the greatest waste of time in the entire world is precisely the solitary person at prayer; and the late Romano Guardini (1885-1968), in his splendid The Spirit of the Liturgy, especially its unforgettable fifth chapter, “The Playfulness of the Liturgy”.

In that chapter, Guardini unwittingly joined hands with his contemporary Winnicott (1896-1971) in the emphasis both came to place on play not as some kind of childish activity but as a unique and necessary component of every healthy adult life–including the Son of Man! For Winnicott it was ultimately about patient and clinician being playful together–playing with thoughts, engendering curiosity about emotions and experiences both old and new, and thereby discovering deeper freedom to move on with one’s life. This model is foundational for my own clinical practice.

For Guardini, the liturgy is rooted in that glorious image of Proverbs 8:30-31: “I was with Him forming all things, and was delighted every day, playing before Him at all times, playing in the world.” This is playing alone in the presence of another with a delight that serves no utilitarian end but is an embodiment of jouissance.

Solitude is indeed useful (as I certainly find it to be), and these authors often do a commendable job of emphasizing its benefits. But it can and should simply exist some of the time as a place of personal playfulness. Sometimes I literally do wander alone through a nearby rose garden for no other reason than sheer enjoyment. The wondrous array of colors and diverse types of flowers exist solely ad maiorem Dei gloriam.

Solitude: The Science and Power of Being Alone

By Netta Weinstein, Heather Hansen, and Thuy-vy T. Nguyen

Cambridge University Press, 2024

Hardcover, 300 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.