Seizing the Day the Christian Way

Is “seizing the day” the solution to our modern maladies, to the anxieties that we feel? We can see that there is a way of being attentive to the present moment, of carrying out the precise task demanded of us at all times, which is part of the way to holiness. Yet such a way […]

Is “seizing the day” the solution to our modern maladies, to the anxieties that we feel? We can see that there is a way of being attentive to the present moment, of carrying out the precise task demanded of us at all times, which is part of the way to holiness. Yet such a way is far different from the contemporary craze for “living in the now,” or by any other means eating, drinking, and making merry, by living in a brilliant sunshine of the present in order to forget that we will die. So, how do we strike a balance?

Such a life of constant indulgence and distraction is not scriptural in any holistic sense, nor is it Christian, inasmuch as we take the life of the Christian to be modeled on that of Christ. The Bible, though it constantly reads time in the light of eternity, is of all great works of literature perhaps the one most concerned with time. Genesis gives us time’s beginning. Revelation shows us time’s end. We are told the number of Adam’s years and the years of Israel’s enslavement in Egypt. The book of Kings supplies its rhythmic delineation of each king’s reign. Scripture dwells endlessly on the cycles of time, from the seven-day work of Creation to the three-day epiphanic sequences of Sinai, the wedding at Cana, and the Resurrection. The Gospels are filled with phrases such as “on the third day,” “the next day,” “it was then about noon,” “from the sixth hour to the ninth hour,” and “immediately.”

Whereas the great Homeric epics exist in a kind of bright eternity always focused on the present temporal moment—the endless sunshine of figures on Grecian urns poised on the verge of battle or love—the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures hold up the present moment and its extensions against the dark, brooding background of eternity. A figure like Odysseus is the true king of seizing the moment, of taking whatever time presents to him, whether it be a meal in the cave of a Cyclops or a year in the bed of Circe. The background of Penelope and Telemachus, of Laertes and Athena, fades away as he adventures across the Mediterranean. For a figure like Abraham, on the other hand, it is the eternal background of God that at every moment informs his temporal actions.

For the scriptural authors, then, life is not a matter of seizing the moment but of lifting every moment to eternity. The anxiety we experience as a result of time may, under this rubric, become a means of our being stretched with Christ on the Cross toward time’s eternal limit. That is, the more biblical our outlook is, the more our consciousness will expand to the beginning and the end to embrace all in between as a gift of God—and as a sacrifice that the Son offers in His own body to the Father. Still, the temporal distension which all men experience as a prime cause of anxiety is not limited to those of us who sin. We see throughout the Gospels that Jesus does not reduce His ministry to a kind of supreme living in the moment. On the contrary, He is deeply concerned with time, specifically with His hour. He reminds Mary of this during the wedding at Cana. He prophesies three times that He will suffer and die and on the third day be raised. In the Garden of Gethsemane, He looks ahead to His Passion in such agony that blood flows from His pores.

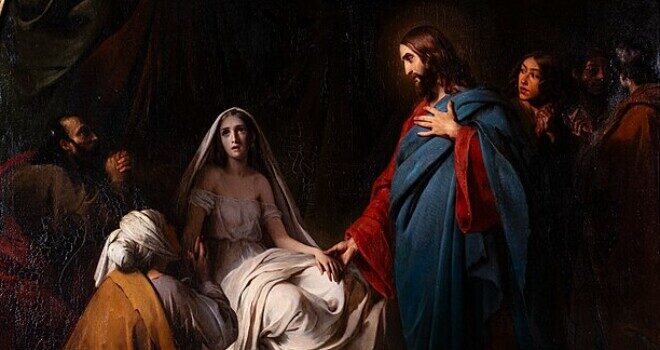

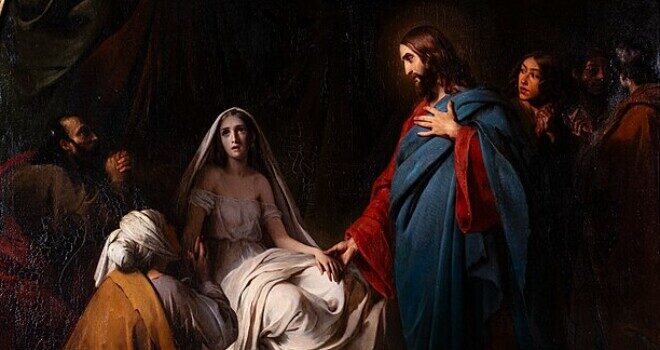

This is not to say that Jesus does not attend with the greatest intensity to the work of each moment. Though He is in some sense always attending to the hour of His being lifted up on the Cross, He attends as well to the sick and sinful herd which meets Him along the way. We witness a supreme example of Jesus’ manner of attending to the present through the eternal in the story of the cure of Jairus’s daughter and the woman with a hemorrhage (Luke 8:40–56). It’s a masterpiece of storytelling. Jairus comes to Jesus, informs him that his daughter is sick, and asks Him to come and heal her. As the Lord passes through the crowd, a woman who has suffered for twelve years with a hemorrhage touches the hem of His garment and is cured, such that Jesus feels the power go out of Him and stops to ask who it was that touched Him.

It’s a moment of the most excruciating temporal anxiety. We can feel the bewilderment of the apostles as they point out the great press of the crowd and ask how they could possibly know who touched Him. We can feel the distress of Jairus, waiting there as his daughter dies, time slipping inexorably away as Jesus stands there, letting the crisis drag on.

And then word comes: don’t bother Jesus any longer. The girl has died. The time to save her has vanished into the past. Jesus reassures Jairus, and us, that the girl is not dead but sleeping. He proceeds to awaken her, and we breathe a sigh of relief with the astonished father.

It is not simply that Jesus knows that He can heal the girl. Rather, as He tells us, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is not God of the dead but of the living (Mark 12:27). In eternity, the girl is always alive. Christ, in the midst of His humanity, looks nonetheless with the Father’s eternal vision. It is this attention to the Father that allows Christ to keep His hour ever in mind even as He performs the work that every moment presents to Him. To be a Christian is in no small part to develop Christ’s attention to eternity and so to equip ourselves for the work of the present. Above all, it is the Lord’s Day which so equips us, teaching us to gather up all the time given us, and all the time given to creation, to lift all up to the Father, and so to participate in the eternal offering of love among the Persons of the Trinity.

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from a chapter in Daniel Fitzpatrick’s Restoring the Lord’s Day, available from Sophia Institute Press.

Photo: Brune-Pagès, A. (1842). Raising of the daughter of Jairus. [painting]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.