Some questions are anathema to human nature and should not be asked

Faith in human life’s inherent value is waning around the world. For now, though, it at least persists on Chesterfield railway station’s second platform, where various iterations of a huge advertisement in favour of life have hung there for as long as I have been catching the train south to London. The billboard pleads with The post Some questions are anathema to human nature and should not be asked appeared first on Catholic Herald.

Faith in human life’s inherent value is waning around the world. For now, though, it at least persists on Chesterfield railway station’s second platform, where various iterations of a huge advertisement in favour of life have hung there for as long as I have been catching the train south to London.

The billboard pleads with anyone considering taking their life to stop, to call 116 123, and to talk. For someone standing there in the shadow of depression, this sign for the Samaritans may be what saves their life; it may be enough to stop them from stepping off the platform.

Suicide prevention charities like the Samaritans attempt to reassure those who feel like they no longer matter. They try to remind the depressed and the suicidal that their depression is a sickness that does not define them, and that their life is worth living. Vital to this is recognising that every life matters in and of itself. Not because of what someone has done or may go on to do for society, but because it is.

Ensouled or not, every person’s life contains the same kernel of dignity. But that idea and value is increasingly under threat in secular modernity.

Canada’s Parliament passed the Medical Assistance in Dying Act (MAiD) in 2016, after the Supreme Court of Canada found that the criminalisation of euthanasia violated fundamental rights. Those suffering from “grievous and irremediable” illness were entitled to an assisted death, it vouchsafed.

But what was supposed to be a narrow path away from the unimaginable pain and suffering experienced by an infinitesimal proportion of society is becoming a highway open to the ill and the infirm. Over 4 per cent of deaths in Canada were brought about through MAiD last year.

MAiD has done much to shift Canada’s view of life’s value, elevating the opinion that life contains value only so long as it is in pursuit of some greater reward. Life alone is not enough, let alone a life encumbered with suffering. Health-care professionals have suggested MAiD to Army veterans suffering from PTSD as well as to the homeless.

The lesson increasingly being taught alongside MAiD is that a life lived with trauma or a life on the streets is no life at all, and warrants being snuffed out. Such a life may not be one that anyone might desire, but that does not mean it is not a life. And in no moral universe is the solution to such a troubled life merely death. Yet almost one in three Canadians would accept poverty alone as a valid reason for receiving a medically-induced death.

Recent amendments to the MAiD legislation would dump even more weight on this side of the scales. Canada’s Parliament intends to allow the long-term depressed and other sufferers of mental illness to become eligible for assisted suicide. For the severely depressed, like Mitchell Tremblay, who spoke to CTV about how his life was “worthless” and about his desire for an assisted death, extending legislation like MAiD to encompass mental illness confirms the deepest and darkest fears of the vulnerable. It tells them that their belief in their degraded self-worth is true, and is shared by the State and so the rest of society. Legislation like this stamps society’s imprimatur upon the tragedy of self-destruction.

In less than a hundred years, society will have gone from viewing suicide with such unease that it denied Christian funerals to those who committed suicide, to providing the tools for suicide. Legislation like MAiD is the Frankenstein’s creature of liberal utilitarian philosophy. Utilitarians, beginning with Jeremy Bentham and his successor and disciple, JS Mill, valorise the pursuit of happiness, and so any of the choices that are perceived as leading an individual to it.

What someone wants, someone should try and get. Such an approach elevates autonomy above all other aspects of the human condition, leaving it as the sine qua non of human dignity. By turning society to such consequentialist ends, the value of life can be put on a scale, and the scale can be tipped in a way that condones and celebrates someone’s decision to end their life as dignified, rather than abjured as fatalistic.

Even philosophies that try to look at the act itself rather than its consequences have been turned towards fatalistic, libertarian ends. Such a fixation upon autonomy as the apotheosis of human dignity was on display in The Philosopher’s Brief, an intervention by six distinguished moral philosophers in a US Supreme Court case on the constitutionality of euthanasia in 1996. The brief, later published in the New York Review of Books, called death “the final act of life’s drama”, and an act that should “reflect our own convictions…not the convictions of others forced on us in our most vulnerable moment”.

But this narrative forgets the role that society plays in the emergence and development of our convictions and beliefs. People are not islands, drawn together only by the tides, but the product of the society they live in and the beliefs of the people within that society. Legalising euthanasia for anything but the most terminal of illnesses forces people to grapple with their morality and their continued existence. It does not respect their autonomy, but intrudes upon it, making them consider a question that is anathema to human nature: “When do I want to die?”

Within their brief, the philosophers claimed that any right-to-die legislation would not draw in more than the most vital, tragic cases, and could not affect those for whom “it is plainly not in their interests to die”. In their view, there was “no suggestion” that governments were “incapable of addressing such dangers through regulation”, and rather than diminish the attention given to palliative care, the need for all alternatives to be exhausted before granting euthanasia would “presumably” improve, rather than degrade, palliative care (the latter of which is exactly what is happening in Canada and places where euthanasia is being made more accessible).

Written before the turn of the millennium, they did not have the evidence that the MPs in Westminster have before them as they grapple with the question of euthanasia in the UK. In a recent debate in Westminster Hall, MPs offered up personal stories of their loved ones’ final moments. Almost all of these, whether or not they condoned or condemned euthanasia, were about the elderly suffering from terminal illness.

But the evidence from Canada and from other more permissive regimes is that euthanasia does not stop there. Instead, it evolves, habituating society to expect autonomy over death. It transforms what may be a momentary thought of death into a belief that one ought to die.

Other conceptions of human dignity are available. Autonomy is not the be all and end all. Some things are better left beyond the control of man. For all but the most desperate cases, when we die should be one of them.

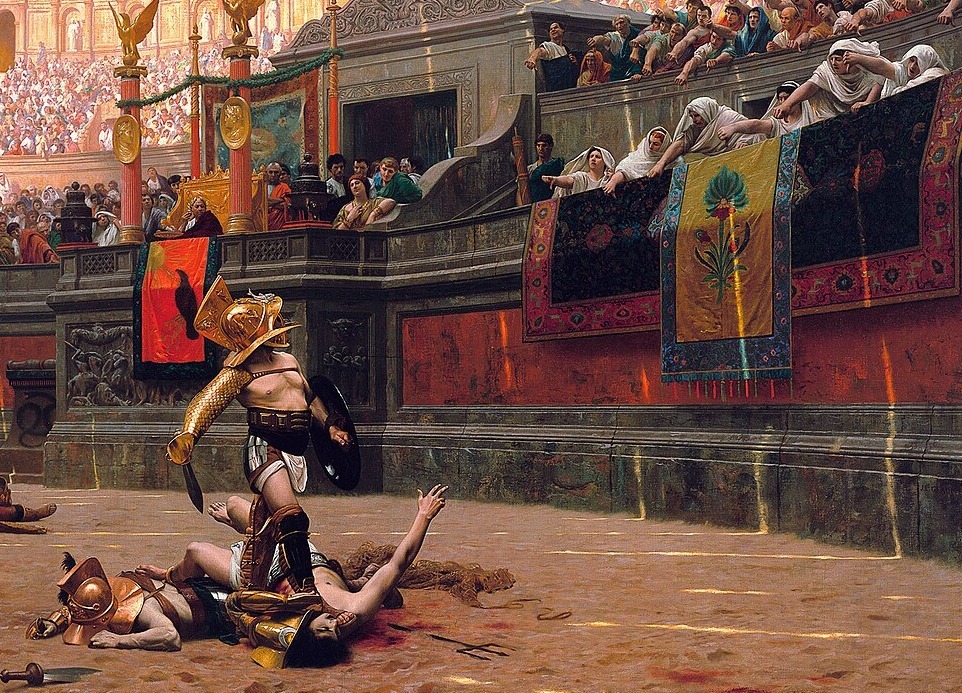

Photo: ‘Pollice Verso’, an 1872 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, named for the Latin phrase meaning “with a turned thumb” that referred to a hand gesture or thumb signal used by the crowds of ancient Rome to pass judgment on a defeated gladiator; image in the public domain.

Nicholas Reed Langen is a writer on legal and constitutional affairs, a former Re:Constitution Fellow (2021-22), and editor of the ‘LSE Public Policy Review’.

![]()

The post Some questions are anathema to human nature and should not be asked appeared first on Catholic Herald.