St. John of the Cross’s Heroic Suffering at the Hands of the Clergy

St. John of the Cross is one of the greatest mystics in the history of the Church. But as we show in our new book, Persecuted From Within, he suffered greatly in the Church controversies of his time. Saint John of the Cross was born into a poor family that was likely of (Jewish) Marrano […]

St. John of the Cross is one of the greatest mystics in the history of the Church. But as we show in our new book, Persecuted From Within, he suffered greatly in the Church controversies of his time.

Saint John of the Cross was born into a poor family that was likely of (Jewish) Marrano origin. He entered the Carmelite Order as Fray Juan de San Matias, but quickly became disappointed in the laxity that was widespread at that time.

In 1567, the recently ordained St. John met St. Teresa of Avila, who was founding her second Discalced convent. He confided in her that he was considering leaving the Carmelite Order in order to live a more rigorous asceticism and enter more seriously into a life of prayer. She told him of her ongoing reform of the order, and that he could live such a life “without leaving Our Lady’s order.” He agreed to help, so long as he did not have to wait long.

St. John accompanied her as she founded two more convents, and after observing their way of life, he became the first Discalced Carmelite friar.

But trouble soon came to the Reform. In May of 1575, the Carmelite Order held a general chapter meeting without any Discalced or even Spanish Carmelites present. The General Chapter banned the Discalced outside Castile and banned all outward signs of the reform, even calling oneself “Discalced.”

In May of 1576, the head of the Carmelite Order in Spain removed St. John of the Cross as confessor at the Encarnacion convent, which St. Teresa writes caused “great scandal.” St. John refused to leave because he had been appointed by Rome, and he had to obey this order. Since he wouldn’t leave, a group of Calced friars kidnapped him and carried him off to a Calced house in Medina. Soon enough, the papal nuncio sent Fray Juan back to Encarnacion.

In August, the Discalced held their own meeting, where they rejected the General Chapter. The Discalced voted to form their own Province, believing they had the support of the papal nuncio.

In December 1577, a group of Calced Carmelite priests, soldiers, and lay Carmelites seized Fray Juan and took him to the Calced house in Toledo. He made no resistance to his captors.

One of the laymen remarked at how horribly the friars were treating Fray Juan, to which he replied that it was not half as bad as he deserved. When the same layman offered to help him escape that night, Fray Juan said that he had no desire to escape.

His captors read the acts of the General Chapter out loud and demanded Fray Juan renounce the Reform. Fray Juan refused.

The friars locked him in what had once been a closet, six feet wide and ten feet long, with no windows. They made him wear the habit of the Calced friars, and he was not permitted to change clothes. His only food was bread, water, and occasionally sardines.

Three nights a week the friars took him into the refectory to eat while kneeling on the floor. After supper, the friars whipped him as they recited the Miserere. When later the friars reduced this practice to only Fridays, Fray Juan asked them in a spirit of mortification to do it more often.

On the Feast of the Assumption, it is said that Our Lady appeared to Fray Juan and instructed him as to how to escape. She promised him that he would be able to say mass again. The next night, August 16, 1578, Fray Juan escaped to the Discalced convent in Toledo, scarcely able to walk. In those first few hours, Calced friars came to the door, but the nuns hid him in an infirmary, which by Providence the Calced friars left as the only room unchecked.

There is no recorded instance of St. John speaking ill of his captors or complaining of his captivity. Such a man was St. John that once upon hearing the word “suffering,” he went into a rapture for more than an hour.

Soon after his escape Fray Juan attended another Discalced General Chapter. The new papal nuncio excommunicated everyone who participated at the meeting—including St. John.

But, as if by some miracle, the nuncio soon softened toward the Discalced. In time, he advised the pope to give the Discalced their own Province, as they wished. A year later, Pope Gregory XIII did just that.

By 1585 the new Province elected a zealous young friar named Fr. Nicholas Doria as Provincial. He immediately reorganized the Province to give himself more power, and when the nuns complained, he threatened to expel them from the Order. St. John was known to be sympathetic to the nuns and Fr. Doria and his inner circle viewed St. John as a personal enemy. St. John soon found himself out of an office for the first time in religious life. St. John rejoiced.

One of Doria’s closest associates opened an investigation into St. John to expel him from the order. He failed, but it caused a great scandal.

St. John fell ill in September 1591, with a fever and inflammation of one of his legs. For medical care, he went to the Carmelite house at Ubeda, “for in Ubeda, nobody knows me.” The Prior at Ubeda openly complained about St. John and gave him the worst cell in the monastery. Some sources suggest that Fray Crisotomo already hated St. John before he came to Ubeda, and that St. John chose to go to Ubeda because of this.

Seeing St. John suffer with joy, the prior underwent a dramatic conversion and last begged for forgiveness. St. John forgave him and died just hours later on December 14, 1591, praying in manus tuas, Domine, comendo spiritum meum.

St. John was beatified in 1675, canonized in 1726, and recognized as a Doctor of the Church in 1926. He is known as the Mystical Doctor.

This article was adapted from Alec’s new book, Persecuted from Within, which is available from Sophia Institute Press October 17, 2023.

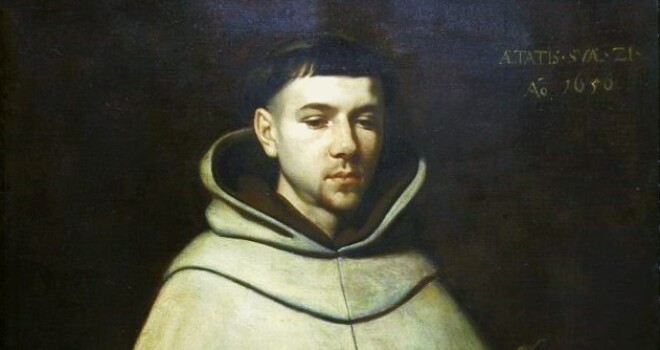

Image: Zubaran, John of the Cross, public domain.