The Catholic Choir and Choirmaster: Handmaid of the Liturgy and Guide of the Faithful

“How freely did I weep in thy hymns and canticles; how deeply was I moved by the voices of thy sweetly sounding Church! The voices streamed into my ears; and the truth was poured forth clearly into my heart, where […]

“How freely did I weep in thy hymns and canticles; how deeply was I moved by the voices of thy sweetly sounding Church! The voices streamed into my ears; and the truth was poured forth clearly into my heart, where the tide of my devotion overflowed, and my tears ran down, and I was happy in all these things.”[1] These are the words of St. Augustine, one of the greatest Doctors of the Church, referring to hearing the people in the church of Milan singing antiphonal chant together, “with great earnestness of voice and heart.”

With the help of St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, the custom of congregational singing, already widespread in the East, was beginning to make its way into the Western Church. Within two hundred years, Pope St. Gregory the Great put his own mark on this work by compiling the then-existing repertoire of chant, earning for it the name Gregorian: music supremely fitting for the liturgy of Holy Mass.

St. Augustine’s testimony describes well the power that music wields in forming morality and character. Music accesses a level of receptivity not available to any other medium; thus it can direct the disposition of the mind and soul, and elicit in the listener any kind of emotion. Given this overwhelming influence of music, the opportunity for misuse is abundant. Pastors must ensure that the musicians in their employ recognize this grave responsibility and have the training they need to use this powerful advantage with great care, lest souls be endangered.

Within the liturgy, there is a trusting and captive audience who, at least on Sundays and Holy Days, are obliged to be in attendance. Anything that happens within the liturgy—be it in the sanctuary or in the choir loft—is assumed by the generality of the faithful to be approved by ecclesiastical authority. The spiritual and eternal context of the Mass adds even more gravity to the pastor’s obligation to choose the right musicians, the right music for the occasion, the proper methods of singing and of playing instruments. Each of these elements should be spotless, unblemished, wholly worthy of serving the Church and her faithful.

The Church has already provided what we need in order to understand and implement the ideal, if we have the humility to hear her voice, but the enforcement of her recommendations is difficult, partially due to the subjective nature of music as an art. Frequently it comes down to the uneven knowledge of our pastors and the variable willingness of musicians to learn and to implement what is expected of them by the Church in her objective guidelines. Pastors can rest assured that being authoritative in regard to sacred music in their parishes does not require them to be experts in the field of music. Our priests are the true proprietors of the sacred music programs in their parish, as they are true teachers of the Faith whether or not they are brilliant theologians.

The Solesmes “Gold Standard” for Gregorian chant

Beginning in the time of St. Augustine until 1,300 years later, right to the present day, the mind of the Church has not changed in her esteem of the greatest form of sacred music, Gregorian chant. It holds the highest place and is the most desirable form of sacred music for use during Holy Mass. The approved version of the chant melodies is the Editio Vaticana (with or without rhythmic signs).[2] Students of the ancient diastematic manuscripts notice a striking unanimity in the notation of many melodies found in different parts of the world, at a time when it was difficult to communicate over long distances. This is a remarkable testimony in itself to the power of Tradition and the universality of the Church.

It is therefore sad to see, at a time in which global communication is in the palm of our hands, sects of “experts” who modify the approved Editio Vaticana according to various academic theories for which they have a personal taste. These ghettos of thought risk corrupting the work done to unify and standardize Gregorian chant by Pope Pius X in the hopes that the Latin-rite Church all across the world can continue to sing una voce.

The Holy Father, Pope Pius XI, in an autographed letter to His Eminence Cardinal Dubois, on the occasion of the Founding of the Gregorian Institute, at Paris, in 1924, writes: “We commend you no less warmly for having secured the services of these same Solesmes monks to teach in the Paris Institute; since, on account of their perfect mastery of the subject, they interpret Gregorian music with a finished perfection which leaves nothing to be desired.” With this quotation of an august commendation, the present Edition is now offered by the Solesmes monks, that the Roman chant may be a profitable instrument “capable of raising the mind to God, and better fitted than any other to foster the piety of the Nations.”[3]

This excerpt from the Introduction to the Liber Usualis shows a decisive satisfaction with respect to the work of Solesmes in authoring the approved edition. In turn, we too should pursue our own mastery of their final product with the same satisfaction. The mastery of the Liber Usualis is itself a lifelong pursuit, as I have learned from decades of singing from it with scholas and choirs in all sorts of contexts. It has brought me untold delight to be able to join or lead scholas almost anywhere in the world because of the use of the Solesmes books and method.

Conflicting factions or new scholarly editions of the chant, whatever their academic merits or aesthetic curiosity, have, in my experience, a polarizing, dispersive, and confusing effect that does not redound to an una voce sound and the edification of the faithful. This is why I believe the greatest effort should be made to adhere to what is universally accepted and agreed upon when it comes to both the sacred liturgy and its Gregorian chant. God is not the author of confusion, division, or disagreement:

Sacred music should… possess, in the highest degree, the qualities proper to the liturgy, and in particular sanctity and goodness of form, which will spontaneously produce the final quality of universality.[4]

The Propers at Mass should be accomplished by the schola cantorum, a group of unison voices only, either men or women, unmixed. The ideal tone is pure and even, without any hint of vibrato or pulsation. Consecutive equal pitches found in the score should not be reiterated, as this destroys the continuity and smooth texture of the blended tone, making it abrupt and sometimes grating. The schola cantorum should strive to achieve the sound of a single voice when singing the chant.

The Importance of Avoiding “Theatricality”

Writers on the topic of sacred music generally quote the most recent papal documents, such as Tra le Sollecitudini, Musicae Sacrae, and Musicam Sacram. But the problems we face in Church music go back a long ways. For example, we read in Pope Benedict XIV’s 1749 encyclical Annus Qui Hunc:

[We] admonish You … that polyphonic music, which is now received by custom in churches, and which is usually accompanied by the harmony of the organ and of other instruments, should be established in such a way that nothing profane, nothing mundane or theatrical, may resound.[5]

Benedict XIV cites his predecessors, sometimes back to the Middle Ages! The Church has long been contemplating music’s effects upon the human person and its proper role and character in worship. For example, the Council of Toledo in the year 1566 was just as adamant about omitting certain sounds of artistic music unbecoming to the liturgy:

It is absolutely necessary to avoid the musical sound that brings something theatrical in the singing of the divine praises; or that evokes profane loves, and warlike deeds, as classical music [classicos modulos] usually does.[6]

We can see that the Church has kept a watchful eye upon the difference between beautiful yet sentimental music and that which is conducive to use in the liturgy, in order to safeguard the prayerful, solemn purpose of celebrating Mass. Sometimes it is helpful to understand what something is not, in order to have a better understanding of what it properly is. Here is one example of how to distinguish between a musical piece that is theatrical and liturgically inappropriate, based on what it lacks, and a piece that is well-suited for liturgy:

Plainchant, executed with due restraint, has a great advantage for the use of the Church. This is because, being unable owing to its gravity to move the affections that arise in the theatre, it is most suitable to arouse those that are proper to the church. Who, in the sonorous majesty of the hymn Vexilla Regis, in the festive gravity of the Pange Lingua, in the mournful tenderness of the Invitatory of [the Office of] the Dead, fails to feel moved either by veneration, or by devotion, or by pity? Every day, these chants are heard, and they always please; while modern compositions, when repeated four or six times, are annoying.[7]

How accurate this assessment is! I can hear the Vexilla Regis or Pange Lingua for the rest of my life and not grow tired of them, while many classical and modern compositions cannot hold a candle to the staying power of the traditional sacred music repertoire of the ages. As a composer myself, I constantly feel the truth and influence of Pius X’s judgment that chant must be the model for church music, and my hope is to compose pieces that are somehow in harmony with the genius and spirit of chant.

Aside from the specific selections, another way the disposition toward theatrical performance is manifest in parishes today—even when the music is traditional and beloved—is through the use of manneristic (overdone) interpretation, attention-getting alternation between different sections of the choir, or the contrast of choir and soloists. Although alternation between chant and polyphony in the same piece and the use of falsobordone, organum, or droning can all be done tastefully and appropriately, they should not be so frequently employed that the purity and simplicity of the Gregorian chant is stifled or compromised. It is best to use such things as ornaments or enhancements for greater solemnities.[8] Pius X is right to say that a liturgy sung only in Gregorian chant is lacking nothing, is no less noble, than one that involves other kinds of music. The chanted liturgy is the norm: it is our musical daily bread.

It is also required that for a piece to be sacred and appropriate, the words sung must be understood by the people, regardless of whether the score is monophonic or polyphonic:

Let chant and sound be grave, pious, and distinct, and suited for the divine praises in the house of God, that simultaneously the words as well may be understood, and those listening are excited unto piety.[9]

Although one cannot arrive at a tidy formula, there is a point—we have all experienced it—at which even beautifully written compositions or fantastic artistry brings too much focus on either the artwork or the musicians, thus causing the music to desist in being prayer. It ceases to minister as a servant whose sole purpose is to elevate the mind and heart to God. In the words of Benedict XIV, describing the classical music of his day, which had invaded the churches:

I would say, O ye musicians, that in churches there now dominates a kind of singing that is new but deviant, abrupt, dance-like, and assuredly insufficiently religious, more in harmony with the theatre and with balls than with the Church. We seek after artistry, and we lose the pristine zeal of prayer and chant. We take counsel in curiosity, but in reality we neglect piety. For what is this novelty and frivolous method of singing, unless it is music in which cantors are become as actors, one of whom now sings, then two at once, then later everyone sings together in tuned voices, and then again one triumphs alone with the rest to follow in a short while.[10]

Benedict XIV (truly an anticipation, in this regard, of the great liturgist Benedict XVI!) describes where the true source of musical prayer comes from:

Singing to God is not by voice but by heart; and gullet and throat are not to be anointed unto the custom of tragedians, that in the Church theatrical tones and canticles may be heard; but in fear and in deed, in the knowledge of the Scriptures.… There is no shortage of many learned writers who acridly reprehend the patient toleration of stageworthy sounds and singing in churches, and pray that abuses of this sort be banished.… Likewise, sound or melody consistent with Holy Religion is to be sung; not that which proclaims tragic difficulties, but that which demonstrates true Christianity to you; not that which emits some theatrical odor, but which causes repentance of sinners.[11]

A habit of programming new polyphonic pieces in which the texts are not easily understood either because of how they are set or how frequently the repertoire is changed is a way in which music can begin to be detached from the liturgy and become a sort of island unto itself. Complex music or music that strains against the boundaries of what a lay choir is typically capable of alienates and excludes the congregation, drawing them rather into sentimentality than devotion, and away from what is happening in the sanctuary. The faithful immediately recognize the attributes of a performance and respond to it accordingly. The environment takes on an obvious air that they are expected to be silent spectators and are not welcome to join in. The faithful are then forced to surrender what is rightfully theirs. Mass becomes a seemingly random walk through a foreign land of unknown melodies, without any of the comforts of home. The great strength of simple, traditional, familiar monophonic chants or hymns sung in unison is that they unite the members of the body in a common repertoire.[12]

The Participation of the Faithful in Singing Chant

In addition to the schola singing the Gregorian chants that are proper to the Mass of the day, the Church also reasonably and rightly asks the congregation of the faithful to join in singing the Ordinary of the Mass and the usual responses. Giuseppe Cardinal Sarto, in his letter to Msgr. Callegari in 1897, remarked:

If I could only make the faithful sing the Kyrie, the Gloria, the Credo, the Sanctus and the Agnus Dei, that would be to me the finest triumph sacred music could have, for it is in really taking part in the liturgy that the faithful will preserve their devotion.

This sentiment seems exactly right to me, as a parent and an educator: singing is the most natural and effective way to unify people, and the unison song of the Church penetrates deeply into the memory. The mind of the Church desires not only that there be a worldwide standard for Gregorian chant, as I said earlier, but also that the faithful be offered the opportunity to sing it. In the words of Pope Pius X:

Special efforts are to be made to restore the use of the Gregorian chant by the people, so that the faithful may again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times.[13]

As I have traveled around the world, my observation has been that a congregation that regularly and robustly sings familiar chants and hymns, and especially the Ordinary at Mass, is, unfortunately, the exception rather than the norm. There are several reasons for this, not the least of which is a tendency to favor choirs that perform their musical selections, putting on a concert (as it were) of the most advanced music the singers are capable of, rather than discharging their duty in a spirit of simplicity, humility, and prayerful docility. There are strict rubrics for what happens in the sanctuary during the liturgy. One might say there are “moral rubrics” for the choir and choirmaster, having to do with what is fitting to the nature of the liturgy, its music, and the faithful who take part.

In order to have the courage to sing, the faithful need to have it transmitted to them by the atmosphere and customs that they are welcome to sing. After having been deprived of the opportunity or discouraged from singing for long periods of time, the anxiety of embarrassing themselves “out loud” will be formidable, and old habits are hard to break.

To help, the choir needs to provide a simple and consistent delivery in unison, with moderate but not overbearing volume, and without changes to dynamics or choir section. This will provide the faithful with the support they need to hear the melody clearly, without being intimidated. It is quite common to believe that you can’t draw if you’re not an artist savant, and likewise that you can’t sing if you’re not a trained musician. That’s obviously false!

After enough repetition of a Mass Ordinary (for example, using Mass XI for the Sundays after Pentecost, Mass IX for Feasts of Our Lady, Mass I during Paschaltide) and familiar hymns (Ave verum, Adoro te, Salve regina, etc.), the people will memorize the chants and get stronger as they develop more confidence. The congregation will eventually stand on their own two feet and begin singing robustly. Their liturgical prayer life will have reached a new high. The melodies will start to enrich their whole week ahead, as they float in and out of one’s mind (one sees this especially with children, who will start singing snatches of chant while playing). This is what it means to bring the Faith into the heart and the home. Nothing does it more powerfully than music, but to reap the full benefit one must be active in the music and not passive only.

Talented musicians have a tendency to get bored and may desire to demonstrate their superior skills. They should remember, however, that the choir loft is not a stage and the congregation is not an audience. At very least, distinctions should be made between ordinary Sundays and special feast days, when, as the saying goes, all the stops can be pulled out. Repetition and simplicity are not aspects to be shunned in liturgical music, but must be embraced with humility, in service to the Church. This subjugation of liturgical music in accord with the needs of the liturgy and the faithful was reiterated by St. Pius X when he said:

In general it must be considered a very grave abuse when the liturgy in ecclesiastical functions is made to appear secondary to and in a manner at the service of the music, for the music is merely a part of the liturgy and its humble handmaid.[14]

Bringing congregations, especially in the United States where good music has long been dead and buried, into conformity with what the Church has in mind for how the Catholic faithful pray the Mass in song could take a few generations. For the good of the youth in our midst, we have an obligation to start the process of acculturation to the Catholic Faith, complete with solid catechesis, traditional liturgies, and finally the sacred music found in our great heritage as soon as possible, while they are still young. The place to start this is in the family circle, with the singing of simple chants, hymns, and songs ourselves, but it should find its fulfillment in church when families come together for common public worship.

With God’s help, eventually the Church will be able to reestablish the same depth of Catholic culture observed by St. Jerome: “They who went into the fields might hear the ploughman at his alleluias, the mower at his hymns, and the vine-dresser singing David’s Psalms.” Let us pray earnestly for the full restoration of musica sacra in the minds and hearts of the faithful, to strengthen the Church militant in the steadfast profession of the Catholic Faith.

Dr. Kwasniewski would like to thank the musician who suggested the publication of an article on these topics and whose help was indispensable to its completion.

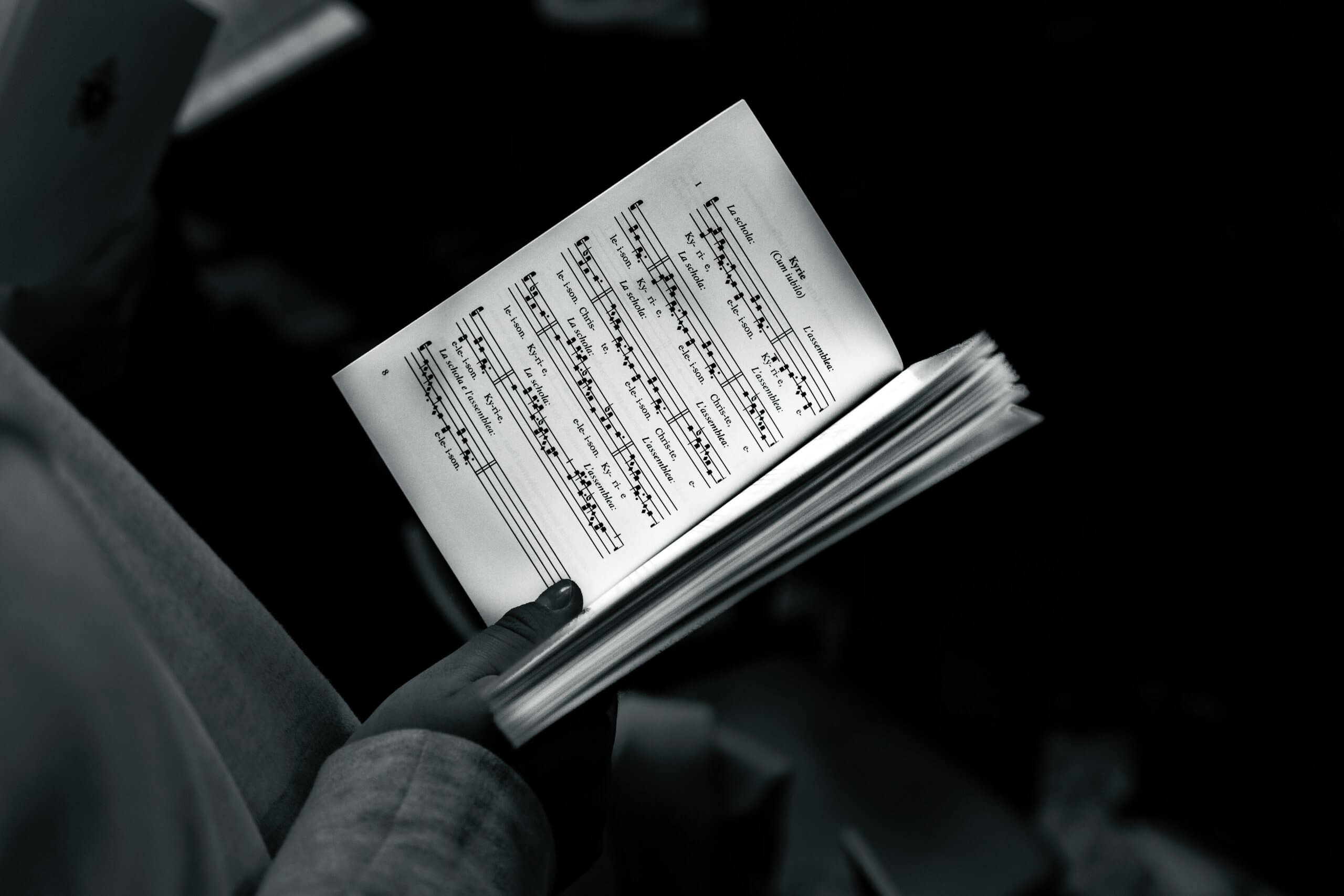

Photo by Àlex Folguera on Unsplash

[1] St. Augustine, Confessions.

[2] Pius XII, De musica sacra et sacra liturgia (1958), §59b.

[3] Introduction to Liber Usualis (Feast of St. Gregory, 1934).

[4] Pius X, Tra Le Sollecitudini, §1.2.

[5] Benedict XIV, Annus Qui Hunc, §3.

[6] Council of Toledo, Conciliorum Collectio, vol. 10, p. 1164. The entire paragraph here is wonderful: “Cum ea, quc in ecclesius cantantur ad dei laudem celebrandam eo debeant catari modo, quo populi intelligentia, quantum fieri possit, erudiri valeat: & religiosa pietatis, ac deuotionis moderatione, piorum auditorum mentes ad diuinae Maiestatis cultum, & coelestia desideria excitari queant: caueant Episcopi, ne dum in chorum Musicorum modulos vocum omnis generis discrimine confulos admittunt, Psalmorum, & aliorum, que cantari solent, verba obscurentur, ac simul strepitu incondito sensus sepeliatr: sic denique Misicam, quae organica dicitru, retineant, ut eorum quae cantantur verba & intelligi possint, & potius pronunciatione, quam curiosis modulis audientium animi diuinis laudibus afficiantur. Sed & illud maxime cauendum erit, ne ipsius Musicae sonus quid Theatrale, aut quod impudicos amorum, bellorumue classicos modulos referat, in Dei laudibus decantandis imitetur.”

[7] Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro, Teatro crítico universal, discourse 14, § III.

[8] Pius X, Tra Le Sollecitudini, §IV.11.

[9] First Provincial Council of Milan, Conciliorum Collectio, vol. 10, p. 582.

[10] Benedict XIV, Annus Qui Hunc, §9.

[11] Benedict XIV, Annus Qui Hunc, §6.

[12] Note that I am not saying the faithful should be singing everything; this is both impossible and undesirable. Rather, the music sung by the schola or choir along should nevertheless be the kind of music that can become familiar to the congregation over time and does not have the character of a performance. Once again, the Gregorian chant shines out as perfect in fulfilling these requirements. Pius X addresses an extreme version of the problem: “In the hymns of the Church the traditional form of the hymn is [to be] preserved. It is not lawful, therefore, to compose, for instance, a Tantum Ergo in such wise that the first strophe presents a romanza, a cavatina, an adagio and the Genitori an allegro” (Tra Le Sollecitudini, Instruction on Sacred Music, §IV.11c).

[13] Acta Sanctae Sedis, Vol. XXXVI, §3. For more such quotations, see Peter Kwasniewski, https://onepeterfive.com/why-gregorian-chant-and-why-sung-by-the-people/.

[14] Pius X, Tra Le Sollecitudini, Instruction on Sacred Music, §VII.23.