The Good and the Bad to Asking “Why”

A Reflection for the Feast of St. Thomas the Apostle “Thomas, called, Didymus, one of the Twelve, was not with them when Jesus came.” (Jn 20:24) When mystifying circumstances beyond our control befall us, our human inclination is to ask, “Why?” Perhaps we sincerely pray about a decision, but then the outcome of that decision […]

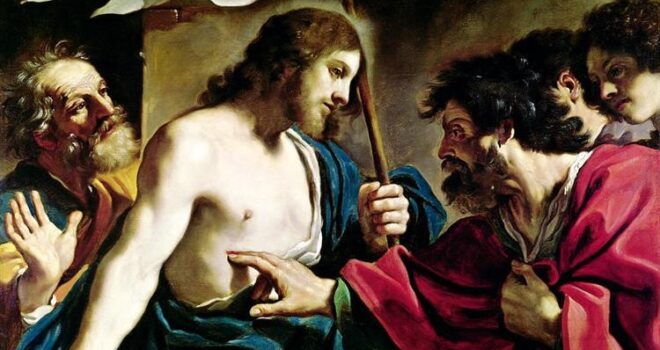

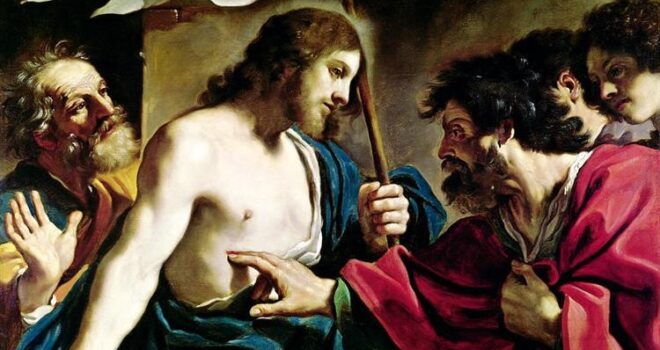

A Reflection for the Feast of St. Thomas the Apostle

“Thomas, called, Didymus, one of the Twelve, was not with them when Jesus came.” (Jn 20:24)

When mystifying circumstances beyond our control befall us, our human inclination is to ask, “Why?” Perhaps we sincerely pray about a decision, but then the outcome of that decision turns out badly; perhaps we had plans, but then the interference of others thwarts those plans, and we are left with a circumstance we did not want, did not ask for, and would never choose. In such cases, who wouldn’t be tempted to ask, “Why?”

Now, the question of “why is this happening to me” isn’t always a fruitless one. If it is being asked from a disposition of peace, with a sincere desire to understand what the Lord is doing in our lives so that we can grow in holiness, then that kind of “why” is beneficial. It is a question that is satisfied with not knowing the answer until the Lord sees fit to reveal it to us; it is a question that remains trusting and peaceful as we wait. We recognize that this period of uncertainty is precisely the time when God is doing something beautiful in our souls. We are growing.

All the way to heaven is heaven, because Jesus said, “I am the way.”

– St. Catherine of Siena

Growing necessarily means we’re not there yet; we haven’t reached our full potential, the place where God calls us to be. And that, of course, is going to hurt. In this sense, it should come as no surprise to us that we’re in pain. It’s even to be expected.

Of course, there’s a different kind of “why” that is of no benefit to our souls. In fact, this kind of “why” inflicts great harm. It is the “why” of self-pity. What makes this kind of “why” so harmful? Because this kind of “why” isn’t really a question. It is a statement that says, “I don’t deserve this.” In other words, when we ask “why” in this way, we don’t trust God’s judgment. We don’t believe His hand is in our circumstances at all. He’s made a mistake. He’s punishing us. He doesn’t love us. And if we start to listen to that voice whispering—and even shouting—such lies at us, then we place our souls in danger of moving so far away from God’s providence that whatever miserable circumstance we find ourselves in will surely spread its misery to everyone around us. Just as the power of trust is very great and will usher in God’s grace, so too is the power of distrust in summoning a cloud of darkness and misery.

So what does all this have to do with Thomas, whose feast we celebrate today? Of all the questions Thomas had on his mind after his sudden realization that the man standing before him was indeed the resurrected Christ, one such question surely must have been: “Why did you appear to all the other disciples, but not to me?” Why did the Lord appear specifically at a time when all the Apostles were together, except for just one? Why did he allow Thomas the humiliation of forever being known as the one who “doubted”? So much so that Scripture scholars tell us that even the name he was dubbed—”Didymus,” (meaning twin)—was likely given to him because he doubted “twice as much” as the others. It hardly seems fair. If only he had been there with his friends when Jesus had appeared…none of this would have happened.

If Thomas had that thought rolling around in his mind, he would have been absolutely correct: Thomas wouldn’t have doubted if Jesus had waited to appear until all the Apostles had been together. So…did Jesus allow Thomas’ public display of weakness because he favored the others over him? Were the others “blessed,” while Thomas was not? Not at all. Jesus doesn’t say, “Blessed are those others who have seen me before you did and have believed.” Rather, Jesus says:

Blessed are those who have NOT seen and have believed. (Jn 20:29)

In other words, the other Apostles were no more blessed simply because they saw Jesus first and then believed. There was nothing “unfair” about the circumstances that befell Thomas after all. The reality is that it could have been any one of those other Apostles who could have doubted. How do we know this? Because they had already doubted before:

…but this story of [the women] seemed pure nonsense, and they did not believe them. (Lk 24:11)

So why did Jesus not appear on the scene to Peter and John, and give them the same speech about how blessed are those who believe but have not seen? Why do we not have a “Doubting Peter” or a “Doubting John” as intercessors in our Church today? Perhaps we might better understand the answer to this question by attempting to answer the question that was likely on Thomas’ mind: why did Jesus permit him this humiliation? The truth is, the “humiliation” had little to do with Thomas and everything to do with the rest of us!

…in him you also are being built TOGETHER into a dwelling place of God in the Spirit. (Eph 2:22)

For the first time, Jesus is sending a message to the rest of the world, down the generations right up to today: we are blessed. As long as we hold onto the belief in the salvific love of Christ in a world that tells us he’s a myth, we are blessed. As long as we hope against hope, even in circumstances that befuddle us and cloud us in darkness, in a culture that does not understand the value of redemptive suffering, then it is we who are blessed.

No question Thomas merited that nickname “Didymus.” Perhaps he really didn’t just doubt; perhaps he truly doubted “twice as much” as everybody else. After all, it’s true that Peter didn’t believe Mary Magdalene’s apparent “nonsense,” but on the other hand, he still “got up and ran to the tomb” (Lk 24:12). So perhaps Thomas truly was more stubborn than the others, more practical—a skeptic, despite all the miracles and healings and love he had witnessed while Jesus walked the earth. But you know what? Thank God for Thomas. It is precisely because of Thomas that the rest of us know with certainty just how blessed we are! And thanks to Thomas, we also know that nothing that befalls us in life—not even the most perplexing, seemingly arbitrary or meaningless of circumstances—is without purpose.

The events we don’t want, don’t like, or didn’t ask for happen to us not because we’re being punished, or because God doesn’t care, or because life is “unfair.” God is cultivating our souls so that we grow in holiness, just like St. Thomas. So blessed are we when we “mourn,” or when “they insult [us] and persecute [us] and utter every kind of evil against [us] [falsely].” Our reward will be great indeed.

Guercino. (1621). The Incredulity of St. Thomas [oil on canvas]. Retrieved from WikiArt.