The Wisdom of the Church and Her Understanding of Man

God made us for this end, that we could be joined to Him in a love freely willed and freely enjoyed, a vision of Him who is our Sovereign Lord, our divine Spouse. God created man in order to divinize him.

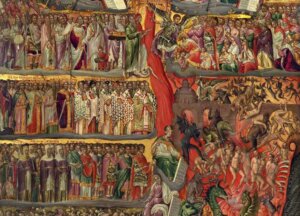

Part I: Hell is Real, and You Could Go There

Part II: Throwing Yourself Away, or Yielding Yourself to God

Part III Purgatory: The Attractive Impulse of His Burning Love

Purgatory and Hell: Forgotten Destinations – Part IV

In this final article, I will speak of the great wisdom of the Church’s understanding of the need for purification, a need that extends not only to the life to come, but to our motives here and now. Why is it we are serving God? What do we love? We are we afraid of?

Irresponsibility in the administration of parishes, a venal promotion of indulgences, and numerous other abuses were widespread on the eve of the Protestant Reformation. Never could it be more truly said, however, that the attempted cure was worse than the disease. Like a barbaric medicine that would rather amputate a wounded limb than take steps to heal it, the Protestant sects banished indulgences and sacramentals, rejected both the sacrament of confession and the doctrine of purgatory, and more drastically, in some instances denied the distinction between mortal and venial sin. In so doing, and quite likely against their better intentions, they prepared the way for the obscuring and eventual undermining of the complex relations between sin and mercy, guilt and grace, purification and worthiness, that are central to the Christian faith.[1]

Anyone who accepts the immortality of the soul and meditates on human wickedness will be able to see the need for an otherworldly purgatory or place of purification, as the pagan philosopher Plato did; anyone who has lengthy experience of spiritual direction will value auricular confession as the most effective means for conquering faults; anyone who understands the twofold constitution of man, sensual and spiritual, will sense the need for sacramentals like icons, holy water, and prayer beads to keep him on the path of virtue. Getting rid of such things would merely show that one’s conception of man is deeply flawed, or that one believes sin can be conquered by oneself alone—a conquest that has surely never been seen in the history of the world—or finally, that one has, in practice, lost sight of the seriousness of sin itself. Without an understanding of what sin is, how it is or will be punished, how it can be forgiven and avoided, its reality is likely to become subjectivized and ultimately discarded.

Those who say that fear of hell is a selfish or unworthy motive for turning to God and keeping away from sin inadvertently demonstrate how little they know about man and his weaknesses. They have not looked closely enough at fallen nature’s weary brow, creased by temptation, stubbornness, and irresolution. Without the fear of hell, hell itself would be far more crowded. Take away this fear and you remove the sting, the trumpet blast, that some wandering sinners need to get them into the confessional and down on their knees. Moreover, faithful Christians need reminding from time to time of what they stand to lose by abandoning the life of grace. St. Thomas Aquinas, a very sensible man, had this to say:

Men avoid wrongdoing by reminding themselves of the penalties: reflecting on damnation, we are warned against sin, for how long, keen, and manifold are the pains of hell: “in all thy works, remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin” (Sir 7:40).[2]

One cannot protest strongly enough against authors who attack the Western Church on this matter. An attack on the doctrine of repenting for fear of hell (which is traditionally known as imperfect contrition) stems from a combination of naiveté and pride. Fear of hell may have been abused from time to time by preachers who forgot to mingle mercy with severity. Nevertheless, it is both unrealistic and impious to try to eradicate or denigrate the motive of fear itself, much less the necessary role of fear in the spiritual life of fallen man. Our Church in her wisdom asks us to recite an act of contrition before we receive absolution. The traditional formula, simple though it is, deserves much pondering:

O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee, and I detest all my sins, because I dread Thy just punishments [the motive of imperfect contrition], but most of all because these sins have offended Thee, who art all good and deserving of all my love [the motive of perfect contrition]. I do firmly resolve, with the help of Thy grace, to sin no more and to avoid the near occasions of sin.

It is not difficult to see that if fear of God is the beginning of wisdom, as Scripture teaches, there is reason to believe that fear of hell can be the beginning of sincere metanoia or conversion of heart. As Kierkegaard says:

Alas, just as the teacher’s strictness is necessary at times, not to punish inattention but in order to get attention, in order to constrain the pupil to look at that which ought to be looked at instead of sitting distracted and being cheated by looking at all sorts of things—so also the fear of perdition must help the sufferer to look at that which ought to be looked at and thereby help him to discover the joy of it.[3]

Similar remarks are in order against those who criticize Christians for obeying Christ and His Church “in order to gain heaven.” There may be Christians whose attitude about salvation is a hidden form of selfishness or individualism hiding beneath a cloak of piety. But it is time to recover a vigorous and healthy love of heaven. Did not Christ come to save us, did He not tell us again and again what we must do to save our souls and join Him in paradise? Is it not evident from His loving words, especially in the “farewell discourses” recorded in the Gospel of St. John, that He longs to bring us into the kingdom of His Father and seat us at the marriage feast of the Lamb? It is no less clear that His disciples have always labored to gain the beatific vision and its perfect communion with God, that the whole New Testament takes the theme of salvation as its “agenda,” and that the Church in her wisdom has taught us to seek salvation before and above all other things.[4] Let us state it plainly: the eclipse of heaven is one of the worst results of the “turning to the world” that was promoted in the name of Vatican II. God did not create us to live forever in this world, which is passing away, and which all of us must let go of. Before we know it, we will be on our deathbed, and the only question that matters will be: What have I lived for? And where am I going now?

God made us for this end, that we could be joined to Him in a love freely willed and freely enjoyed, a vision of Him who is our Sovereign Lord, our divine Spouse. God created man in order to divinize him. As the Catechism teaches (1024): “This perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity—this communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed . . . is the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness.” To dwell everlastingly in the kingdom of heaven, wedded to God by a bond of indissoluble love, is our perfection, the final and all-surpassing gift of love He has prepared for us. By prayer and sacrifice, may we be made worthy to utter the words of St. Ignatius of Antioch: “There is living water in me, water that murmurs and says within me: Come to the Father.”[5]

(This series includes material originally published in The Catholic Faith, vol. 5, n. 2, March-April 1999, published at OnePeterFive in December MMXV).

[1] Protestants reject Purgatory altogether, but the Eastern Orthodox theologians have a different problem. They reject purgatory because they maintain that, owing to the ontological status of the creature, there can be no place for a temporary purification; heaven involves, rather, an eternal purification of the saints. But this position is false for two reasons. First, a soul that bears the stains of sin cannot be admitted to the divine presence at all; it must first be made holy to its fullest capacity. Second, there is not an infinite potential for holiness on the part of a finite creature; there is only so much goodness that a human being can possess. This is the goodness required for heaven, and once a soul has attained it by the grace of God poured out in the purifications of the “middle state,” there is no need for still further purification of uncleanness or unworthiness. The intellectual creature is not unworthy of the divine presence simply by being a creature, but rather, by being an unfaithful servant. When its infidelity is cured, it can stand humbly but worthily before the Almighty. The difference between West and East is rooted in a much deeper difference, namely, whether or not the blessed enjoy the immediate vision of the divine essence in itself; and it may also be connected to a difference in the degree of dignity accorded to man as an image of God. The Western insistence on purgatory, on the need for purification, stems from a higher estimation of the worthiness this image is capable of possessing in the very presence of God.

[2] Gilby, Theological Texts, 264.

[3] Christian Discourses, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 142.

[4] To think that we could somehow love God “just for His sake,” and not because of our radical neediness, our hunger and thirst for His presence, our wants— even Kierkegaard, no friend to Catholic theology, sees the error, the blasphemy, of this. See “All Things Must Serve Us for Good—When We Love God,” in Christian Discourses, 188.

[5] Quoted in CCC 1011.