To a Seminarian Midway: Is It Worthwhile to Start Over?

This is how most secular clergy spend half of their lives or more, while their consciences whisper: “This is wrong. Why am I taking part in it?”

A young man sent me a letter in which he expressed his perplexity about whether he should join a community that celebrates both “forms” of the Mass, or one that is exclusively traditional.

Dear Friend,

Thank you for writing to me about your challenging situation. You have completed much of your time at seminary, but are experiencing doubts about the path ahead. Believe me, you are not alone in this; many men who believe they are called to the priesthood are really struggling with this question of whether they can or should celebrate the Novus Ordo at all. And it is not difficult to see why it is a struggle.

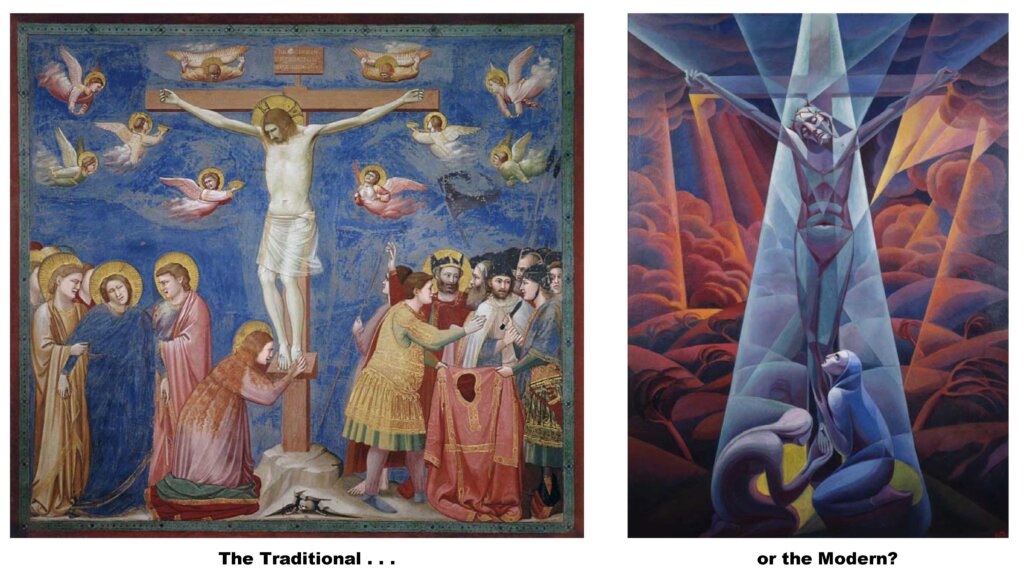

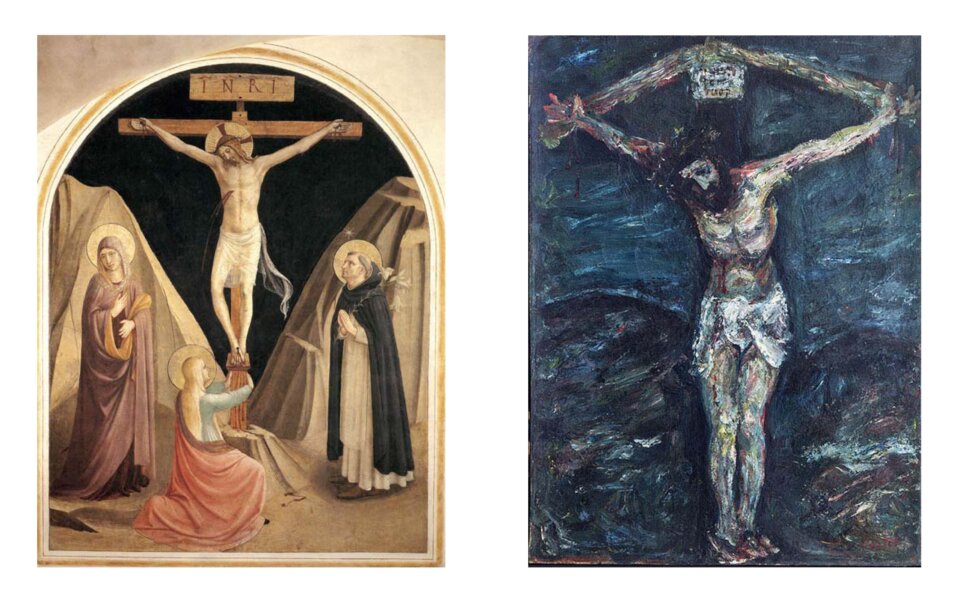

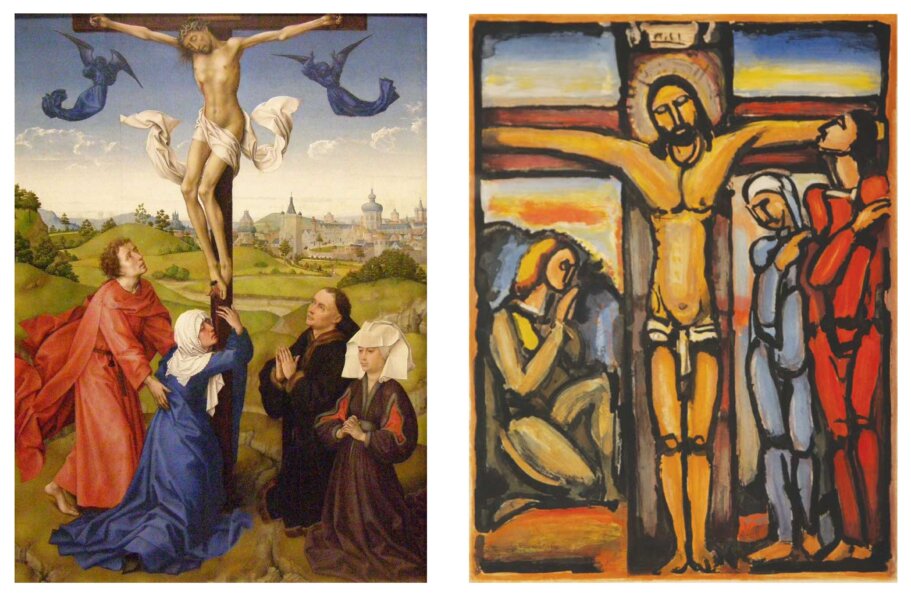

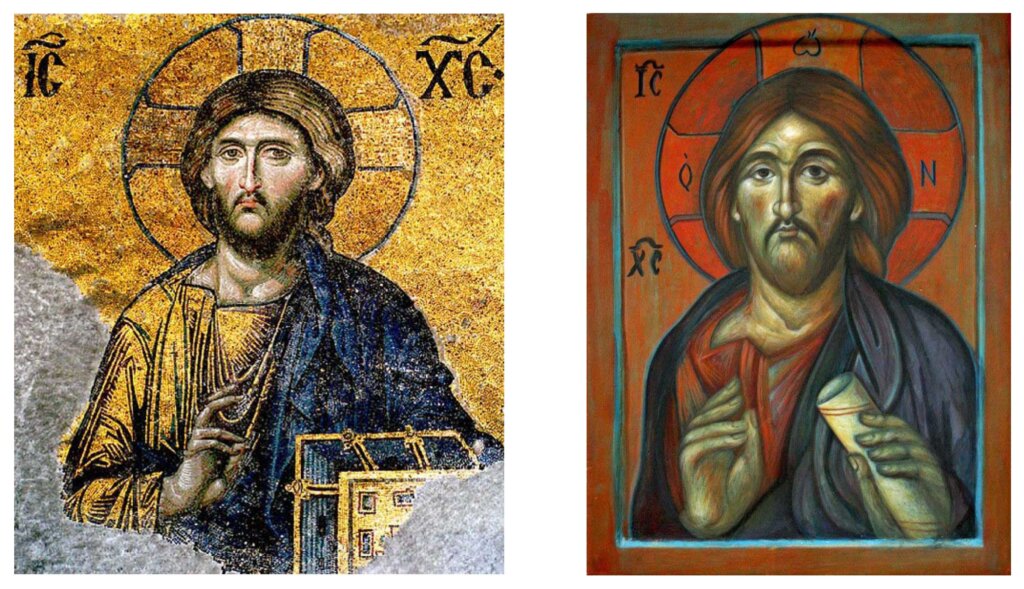

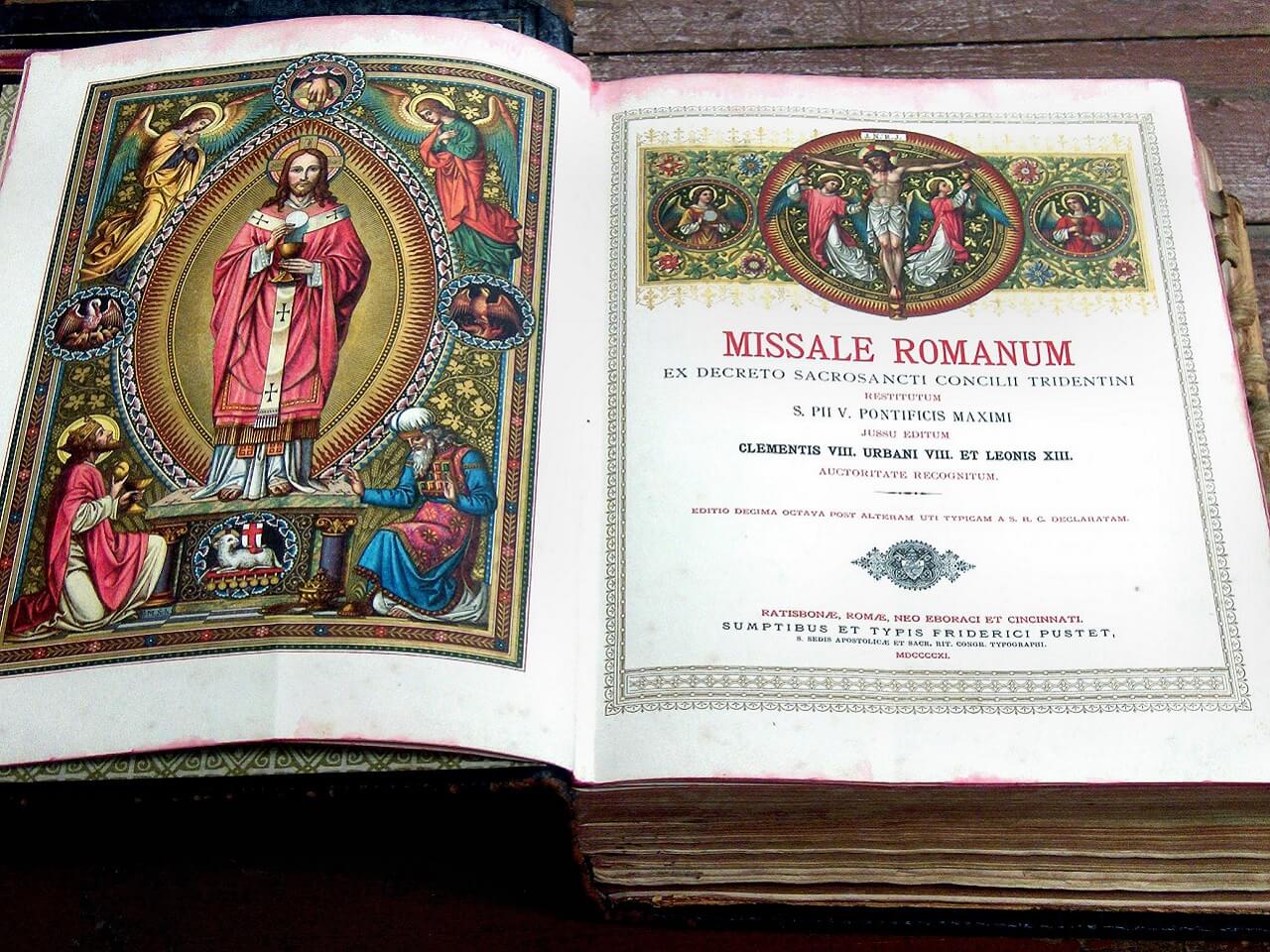

By this time, decades after Montini ramrodded the new books into effect, we are now so fully aware of the deficiencies and deformations present in all the “reformed and renewed” rites—especially when seen against the vivid backdrop of their august Western predecessors and Eastern parallels—that it is hard not to be acutely aware that one is giving the Lord second-best by offering Him, as it were, mangled goods, as far as liturgy as such is concerned. Yes, the lamb of sacrifice is still present, and that is why it is not an empty show, as Protestant services are; but there is that dimension of fittingness and authenticity that goes well beyond legal validity, opening out to fullness of orthodoxy, the spirit of reverence, piety, and devotion, the supply of spiritual nourishment. Liturgy is the icon before which the priest will be spending his life, and in the image of which he will be molded. Does he wish to look like a Fra Angelico, or like a Picasso? (Below I have provided some visuals to illustrate the point.)

In any case, the difference between old and new liturgies is not a matter of mere aesthetics, as you rightly say. One can dress them up quite similarly, but I’m afraid it is like the difference between the rightful heir and the nouveau riche upstart. The one has class, culture, manners, a rich family history, unselfconscious naturalness; the other is a well-dressed boor catapulted into position by papal fiat.

Speaking with many priests who celebrate both “forms” has taught me that they often suffer terribly from the practical schizophrenia that results. In this rite, I genuflect right after the consecration, to adore my God; but in that other rite, I lift Him up straightaway for the people to see, even though every fibre of my being wants to kneel like the Magi. In this rite, I kiss the altar repeatedly, bestowing on it the ardor of my faith and my desire for eternal union with Christ, while in that other rite, it’s one kiss to start, one to finish, and then we’re done. One could find multiple examples ad nauseam.

We are not dealing with two forms of the same rite; we are dealing with two different rites that share a generic format and a smattering of texts, but are otherwise different worlds to inhabit. It seems to me that the partisans of biformality salve their consciences or at least medicate their wounds by the copious provision of smells and bells, which admittedly greases the skids. Quite a bit of reverence can be stirred up by the use of chant, Latin, ad orientem, the right vestments and vessels, etc. This is far better than the feral Novus Ordo found in the wilds of suburbia. Still, window-dressing only goes so far when there are profound differences in content between the missals, the calendars, the rubrical and ceremonial worlds, and the spirituality they embody and inculcate.

In short: a priest is a priest because he is ordained to offer sacrifice. Everything else flows from that. Therefore, a calling to the priesthood cannot be separated either theoretically or practically from the question of the sacrifice to be offered—and we cannot just “offer sacrifice” generically, it must always be within a certain tradition, Eastern or Western; within a certain rite or use, as Roman, Ambrosian, Mozarabic, Anglican Ordinariate, Montinian (that is, Paul VI’s); and with a daily dependence on a rule of life and prayer centered on the Mass and the Divine Office.

None of this is news to you. The question is, what to do? I fully appreciate the desire not to repeat seminary! All the same, I have met older seminarians who, after some years in a diocesan seminary, decided to start over in one of the traditional communities—the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, the Institute of the Good Shepherd, or a monastery such as Clear Creek, Norcia, or Silverstream—and say it’s the best decision they ever made. The academic formation was vastly superior and the fully integrated traditional liturgical life gave them a combination of ardor and peace that they had never experienced in all the tense years of trying to hide their true thoughts and feelings. A sound formation is a rock-solid foundation of a fruitful priestly life, and if the Lord in His inscrutable Providence leads you to a new start, bless His Holy Name for giving you that marvelous opportunity to dig a deeper foundation and to build higher with His help.

With regard to secular clergy, the enormous problem of our times is, of course, the episcopacy itself, which has lost its “first love,” namely, the offering of divine worship in the splendor of truth and in continuity with tradition. While there are a few happy exceptions, the majority of bishops are becoming worse over time, as they desperately hold on to their power and the dream (really, nightmare) of the Second Vatican Council “new springtime.” Years ago I read the saying “the crisis in the Church is a crisis of bishops,” and that seems to me exactly right. As St Gregory Nazianzen says:

The light and eye of the Church is the Bishop. It is necessary then that as the body is rightly directed as long as the eye keeps itself pure, but goes wrong when it becomes corrupt, so also with respect to the Prelate, according to what his state may be, must the Church in like manner suffer shipwreck, or be saved.[1]

If a conservative or traditionally-minded young man chooses to enter a diocesan seminary because the bishop at the time is good, how will he know what the next bishop might be like? What of the hundreds of seminarians around the world who entered under Summorum Pontificum, looking forward to learning and offering the traditional Mass—and then were ordained after Traditionis Custodes when the axe had fallen on their hopes, severing their future from the Church’s past? The diocesan route is truly a treacherous path strewn with immense obstacles and mortal perils. That does not mean it should not be trodden by some; but they must have nerves of steel and invincible courage, and be willing, for example, to train themselves secretly to offer private Mass, which no earthly prelate can take away from them.

Some time ago for lectio divina I was reading the book of the prophet Jeremiah, and was struck by how it depicts the rulers and princes becoming more stubborn and more cocksure as the fall of Jerusalem comes closer and as Jeremiah’s warnings become blunter. Isn’t that exactly what we are witnessing? The practicing laity see very clearly what is going on, but the rulers and princes dig in their heels and will not change course, will not repent of the folly of modernization and pseudo-inculturation. So their house is doomed and it will fall in. It astonishes me that more bishops have not awakened to the obvious fact that if they actually want more priests, they will have to welcome young men who are simply not interested in the modern papal rite and want to do the old Latin rite. I suppose this shows that they would rather see their churches closed and their dioceses shrivel than allow the Latin liturgy a place of honor. This in itself speaks volumes, does it not? It’s no exaggeration to speak of a silent apostasy of the hierarchy. Anyone who is committed to a path of failure is not committed to the Lord of truth.

Meanwhile, where is growth taking place? In the traditional communities that, in spite of a precarious canonical existence, flourish with clergy, religious, and faithful. This, then, is why young men are thinking seriously about the Fraternity of St. Peter, the Institute of Christ the King, the Institute of the Good Shepherd, the Sons of the Most Holy Redeemer, the Missionaries of Saint John the Baptist, the Canons Regular of the New Jerusalem, and other orders, institutes, and communities founded on the rock of the traditional Latin rite. They offer something utterly consistent and coherent, classically Roman, and there is great peace of mind in knowing, in advance, that one will not be called upon to engage in, or tolerate, liturgical abuses and aberrations, which is pretty much how most secular clergy spend half of their lives or more, while their consciences whisper: “This is wrong. Why am I taking part in it?”

It seems to me, as a last point, that it’s not impossible in good conscience to join a community that uses both rites—the Roman rite and the modern papal rite—as long as one does so with a mental qualification that one will celebrate the Novus Ordo only when required to do so by one’s superiors (then it would be an act of obedience), and only if there were no liturgical abuses asked or expected of you. I know of communities in which many of the fathers have a decided preference for the old rite and who do it as often as they can privately, and will increase it publicly as circumstances allow. Since the old rite is already part of their life, you, as a member, would be nourished by it both in private and public celebrations. In this way, your priestly life could still be organized around the traditional liturgy, with the reformed liturgy as a peripheral or marginal reality to be tolerated.

Needless to say, this is by no means an ideal solution, for all the reasons given above (and, in greater detail, in my books); but it has a certain pragmatic appeal, and for some it may be the only practical way forward. In the long run, I believe that such communities will either eventually come around to a full traditionalist view and practice, or will at least show respect to those of their members who have qualms of conscience about using the new books.

I hope some of these reflections will prove helpful to you in taking your next steps.

Warm regards, in Christ,

Dr. Kwasniewski

Photo by Allison Girone.

[1] Quoted by St Thomas in the Catena Aurea on Luke 11.