Where Secularism Fails | Commonweal Magazine

For decades, secular liberals have been warning about the evil of mixing religion and politics, insisting that religion remain a private matter. But what if it is religion that provides us with the social and moral practices needed to defend human dignity? What if we need a religious tradition’s strong sense of the past to […]

For decades, secular liberals have been warning about the evil of mixing religion and politics, insisting that religion remain a private matter. But what if it is religion that provides us with the social and moral practices needed to defend human dignity? What if we need a religious tradition’s strong sense of the past to bind us to one another and to a common future? After all, religiously motivated political movements have helped accomplish a good number of liberal goals. Egalitarian religious convictions helped fuel the American Revolution, abolitionism, the Progressive Era, women’s suffrage, the New Deal, the civil-rights and the anti–Vietnam War movements. Why would liberal secularists want to deprive the nation of the energies of religious people, especially when Christianity’s special regard for the poor and distrust of wealth and worldly power are among its most authoritative teachings?

Writing about the “folly of secularism,” the philosopher Jeffrey Stout, who is not religious himself, put it this way:

If I am right in holding plutocracy to be the most significant contemporary threat to democracy, the pressing question is how to build a coalition to combat the threat. The answer, I submit, is not to exclude religious moderates…. If major reform is going to happen again in the United States, it will probably happen in roughly the same way that it has happened before. It will not happen because of secularism, but in spite of it.

Michael Williams and Norman Mailer both insist that at the center of existence there is a mystery, not an algorithm or a void. If we are to preserve our humanity and our democracy, we must also preserve that sense of mystery. Mailer put his faith in democracy in theological terms: “America—the land where a new kind of man was born from the idea that God was present in every man not only as compassion but as power, and so the country belonged to the people.” That is a sentiment shared by the founders and subsequent editors of this magazine. It is a precious, if precarious, legacy.

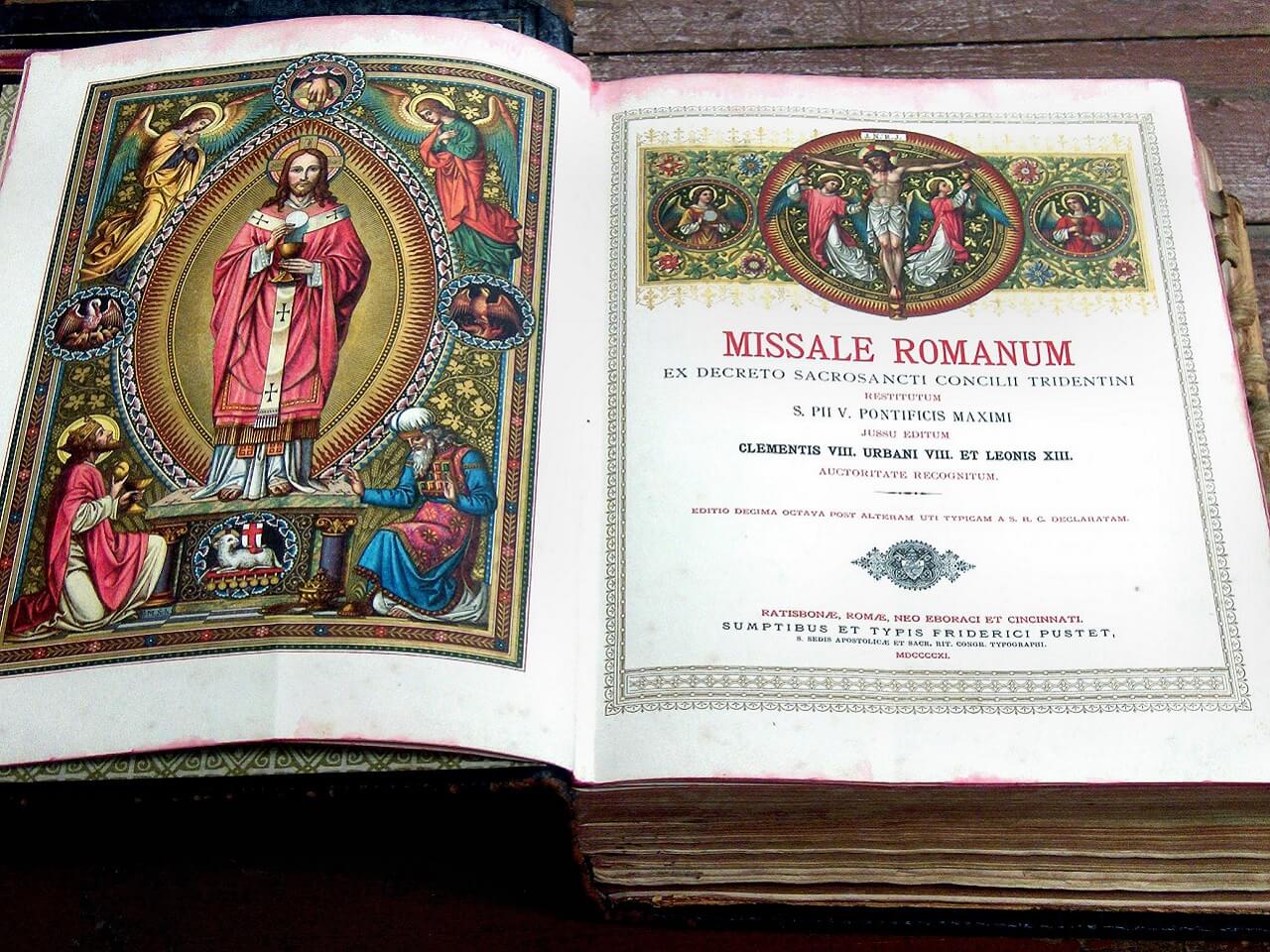

A hundred years ago, Michael Williams asked if Catholics were prepared to spread the doctrines of their Church with conviction and passion. Seventy-five years later, the historian Eamon Duffy answered in the affirmative, as we all should in celebrating the centennial of this magazine. “We [are] too inclined to forget that a Catholic response to the needs of the world needs to be Catholic as well as responsive, if it is to be of any use to a world that has never needed the wisdom of Catholicism more,” Duffy wrote. “I could find no way of holding on to the values of Christianity while denying the account Christianity gave of reality.”

Duffy urges us to trust and keep faith with the Catholic tradition, not an easy thing to do in a time when all inherited authority is deeply suspect. The tension between Catholicism and contemporary secular culture, already strong, will likely grow stronger. The Church cannot simply be assimilated to secular moral norms without losing its identity, but the pressure to assimilate will intensify. It will be the job of Commonweal, as it always has been, to resist that pressure without succumbing to sectarianism or giving up on American democracy.

This article was published in Commonweal’s hundredth-anniversary issue, November 2024.