Why we must recover St Thomas Becket: Catholic England’s standard bearer against secular tyranny

In August 2023, one of the foremost newspapers in the United Kingdom exhumed an old contention from the dirt after it featured a curious story entitled, rather simply, “Protestants added the ‘à’ to smear Thomas Becket”. The article, published by The Times, revealed that late 16th-century Protestant partisans and propagandists had taken to the history The post Why we must recover St Thomas Becket: Catholic England’s standard bearer against secular tyranny appeared first on Catholic Herald.

In August 2023, one of the foremost newspapers in the United Kingdom exhumed an old contention from the dirt after it featured a curious story entitled, rather simply, “Protestants added the ‘à’ to smear Thomas Becket”.

The article, published by The Times, revealed that late 16th-century Protestant partisans and propagandists had taken to the history books in an attempt to rewrite narratives surrounding St Thomas of Canterbury, a heretofore beloved hero and martyr of medieval Christendom.

One such tactic they deployed to undermine the enduring reputation of valour and prestige attached to the man was to insert a hitherto non-existent “à” in between his fore- and surnames. The aim was to both distance his person from the modern era in which the Protestant “reformers” were dealing and to fabricate associations to the rural ruffians found in tales about Robin Hood such as George-à-Green or Alan-à-Dale.

Thus, the revisionists sought to give Becket rustic, bawdy and folkloric connotations, weakening (it was hoped) any sense of the hard historicity to the story. A naïve hope given the unusually extensive range of detailed contemporary sources we have on his life and martyrdom in a variety of languages – but an undermining, nonetheless.

This recent revelation, uncovered by historians and circulated by The Times, draws attention to an enduring truth: the enemies of the Church have consistently deliberated it to be particularly crucial to control or suppress the narrative surrounding this specific Saint. Considering why will be indispensably beneficial to Catholics who would wish to see the Faith restored in our civilisation.

So who is this figure simultaneously regarded as such a historiographical threat by anti-Catholics and yet comparably obscure to Catholics themselves – even those who hail from his own land?

Thomas Becket was born in east London to an essentially middle-class family. As a young man he rapidly rose through the ranks of political society. In 1155, the King named him Lord Chancellor of England – a position to which another saint named Thomas would be elevated nearly 400 years later (but more on that later).

Henry II was a man whose primary ambitions and preoccupations were worldly rather than otherworldly. To add to this, contemporaries note Henry’s short temper and merciless streak.

Henry put Becket to great use in exacting funds from his subjects. When Becket proved competent at the task, the King nominated his chancellor for the position of Archbishop of Canterbury: Primate of England and thus the highest authority in spiritual matters in his entire kingdom.

Senior clerics had played instrumental roles as partisans in the preceding period of volatility and civil war between the Empress Matilda and Stephen of Blois (his mother and second cousin respectively) known as “the Anarchy”, and Henry had no intention of encountering or tolerating clerical opposition.

As award-winning philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre describes:

“Henry was primarily concerned to increase the royal power…Becket in turn represented more than the manoeuvrings of ecclesiastical power, however much these preoccupied him. Embedded within the self-assertion of episcopal and papal power was the claim that human law is the shadow cast by divine law.”

After what was quite a rushed consecration by contemporary standards, Henry’s plans began to unravel as his former friend and appointee began taking his priesthood and episcopacy rather seriously. Archbishop Becket became a noted ascetic – leading a rigorous life of mortification and prayer – and, more crucially, a firm defender of the Church’s rights.

An inevitable conflict ensued. Hilaire Belloc summarises the proceeding events pithily:

“[Archbishop Becket] was asked to admit certain changes in the status of the clergy. The chief of these changes was that men attached to the Church in any way even by minor orders (not necessarily priests) should, if they committed a crime amenable to temporal jurisdiction, be brought before the ordinary courts of the country instead of left, as they had been for centuries, to their own courts. The claim was, at the time, a novel one. [Archbishop Becket] resisted that claim…and within a short time he was murdered by his exasperated enemies.”

After his knights had (apparently) misinterpreted the King’s remark – something along the lines of “will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” – Thomas was assassinated inside Canterbury Cathedral in December 1170. For St Thomas’s part, he is recorded to have greeted his end with full resignation and preparedness, explicitly welcoming his assassins by ordering the barred door to the cathedral they were attempting to break down be opened. He made no attempt to flee. Moments before the fatal blow, he proclaimed: “For the name of Jesus and the protection of the Church, I am ready to embrace death.”

The monk Edward Grim, an eyewitness, who was wounded in the affair, describes how the knights who cleaved St Thomas’s body “purpled” the Church, and how his brains were “scattered across the floor”.

What was the effect of such a callous and scandalous act of regal and civil thuggery?

Firstly, the speed at which the populations of Europe rallied to St Thomas, both literally and figuratively, was utterly remarkable. Little has ever been seen like it. Almost immediately, Canterbury became one of the most visited sites in Europe as Christians were eager to venerate the relics of such a brazen martyr.

Churches dedicated to him sprung up all across the continent: in Spain, Germany, Poland and elsewhere. One of the foremost neighbourhoods, known as Szenttamás, in the ancient medieval and spiritual capital of Hungary, the city of Esztergom, is dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury. It was dedicated to him, along with a church, by Archbishop Lukács Bánfi, who studied with Becket at the University of Paris. Europe was a more united place in medieval Christendom – as the unity and conviction behind the support for Becket illustrates.

Belloc argues this should prove unsurprising: the regular layman knew that his surest guarantee of liberty against the oppression of the rich and powerful was the Church and her morality. Hundreds of thousands flocked to the relics of one of the swords used in the assassination and a part of St Thomas’ skull which can been sliced off. Recorded miracles came rolling in at an extraordinary rate.

As Gavin Ashenden writes: “Over the course of the [subsequent] ten years… 703 miracles were recorded. During 1171 there were estimated to have been 100,000 visitors to the shrine”.

Secondly, in death, like Our Lord, St Thomas won. Belloc correctly insists that although specific arrangements over which the archbishop made his stand – namely the answerability of clergy to secular courts – were eventually waived, this is unimportant. He explains:

“To challenge the new claims of civil power at that moment was to save the Church… [T]he spirit in which [St Thomas] fought was a determination that the Church should never be controlled by the civil power, and the spirit against which he fought was the spirit which either openly or secretly believes the Church to be an institution merely human, and therefore naturally subjected, as an inferior, to the processes of the monarch’s (or, worse, the politician’s) law.”

What happened next was astonishing – and quite unimaginable in any other social order than a Catholic one. The high and mighty were brought low. The proud were humbled. MacIntyre writes of Henry II: “For more than a year before…reconciliation [with the Church and Pope], immediately on hearing of Becket’s death, he took to his own room, in sackcloth and ashes and fasting; and two years later he did public penance at Canterbury and was scourged by the monks.” In contrition and from his own pocket, the King funded the construction of a breath-taking chapel on the centre of London Bridge dedicated to Becket which was one of the architectural wonders of Christendom for centuries.

Becket’s victory was such that despite occasional small skirmishes here and there, the civil authorities across Europe would bow their heads to the Church’s independence and de facto supremacy for nearly 400 years – allowing Christian civilisation to flourish and flower through the High Middle Ages.

Belloc was not overstating the scale of the conflict between Church and State which had been raging until Becket. Only two generations prior, in 1076, the Church had similarly emerged victorious at Canossa after a similar standoff. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV knelt in the snow to beg Pope St Gregory VII’s forgiveness for trying to insist on his right to nominate a wide range of clerical offices (the so-called “investiture conflict”).

The principle for which Becket died – that no one, not even Kings, were above divine law – was reversed at the advent of modernity. As the “Reformation” progressed, civil rulers were again enticed (as their forebears had been) by the prospect of total independence and control of religious affairs within their realms. Albert of Prussia, Christian III of Denmark, Gustav I of Sweden, and (perhaps most crucially) Henry VIII of England seized such power for themselves – embracing schism and heresy.

This time, the martyrs in the vein of St Thomas Becket would not halt or turn back the tide.

In a mysterious parallel, in 1532 another St Thomas (a layman rather than a cleric) defied the self-elevation and flouting of superior religious authority by another King Henry.

St Thomas More was known to be one of the most diligent and morally upstanding men in the realm. A lawyer by trade, as Lord Chancellor (the same role as his predecessor in Canterbury) he found himself unable to recognise the King’s divorce and adulterous relationship with Lady Anne Boleyn, which enraged his hitherto dear friend the King. Imprisoned in the Tower of London, moments before his execution and beheading he serenely summarised the ordered hierarchy of just loyalties a good Christian should hold (and against which modernity was revolting): “I die the King’s good servant, but God’s first.”

With Thomas More’s death, Christian civilisation was being turned on its head and the beginning of a more secular order we recognise – in which the politician and autocrat’s power is total and replaces the absolute allegiance owed to God – was emerging. With the revolt of Henry VIII and his contemporaries, established ecclesiastical authorities in Protestant lands could no longer challenge and subdue the tyranny of civil power – for they were now subject to it.

And so, for Henry VIII, having killed his dear friend who was connected not only by name to St Thomas Becket, the widespread devotion to the old Archbishop of Canterbury across Europe signified an embarrassment and quiet challenge.

Under Henry’s orders, as historian Alec Ryrie notes: “[St Thomas Becket’s] shrine was pulverised [and] a royal proclamation ordered that all memory of him should be extinguished from the English Church – statues, paintings, windows, services all had to go.”

According to some sources, St Thomas’ bones were exhumed and put on trial, found guilty and discarded, such was the threat the dead archbishop posed. St Thomas represented the antithesis to the Reformers’ and secularists’ designs.

The smearing described in The Times was part of the historiographical offensive launched by Henry VIII, his minster Cromwell, and his Archbishop Cranmer. But what significance does this have for us today?

Though the spirit and body are distinct in a human person – and must be each nourished in their respective ways – they are hypostatically united in the human person, and must work alongside one another to the same end (the flourishing of the person), respecting the other’s needs in attaining this goal. At a societal level, the body represents politics and the temporal sphere and secular life; the spirit represents the Church and the Faith, as Pope Leo XIII likened them. They must work together to the same end.

One of the triumphs of modernity has been to relegate religion entirely to the private realm. This enables evils in society to be first tolerated then fester and swell in a way that never otherwise could.

Modernity attempts to make a “liberal distinction between law and morality” as MacIntyre says. How often do we hear the Christian politician leave morality to the individual and private judgement to deflect, while legislating to permit unspeakable evils such as abortion? St Thomas Becket defended the order where no such distinction was possible.

None of this is to say what’s realistic for our times. We must work respectably with the authorities to which divine providence has subjected us. However, we ought not lose sight of the ideal, and should pray for the return of a time when Heads of State were subjected to God and the Pope, sanctity was more abundant, and Jesus Christ was given the private and public dues and influence over laws to which He is entitled.

We ought to appreciate that it is a supreme irony that the nation which produced the martyr par excellence for the defence of the old order should adopt a spiritually- and politically-neutered state religion in Anglicanism and help export the secular order which is its opposite to the far corners of the earth.

However, as historian and author Joseph Pearce notes: our God is a poet. In history as in physics and mathematics and the unfolding of divine revelation, He appears pleased to follow artistic forms, rhythms, and patterns and symmetries. We may remember, for example, the filial sacrifice of Isaac, Abraham’s son, shortly after the beginning of the Bible, fittingly mirrored by the filial sacrifice of Jesus, Adonai’s Son, shortly before its end.

The martyrdom of one St Thomas placated one tyrannical Henry and saved the unity and order of Christendom for generations. Yet the parallel events of their respective namesakes resulted in the reverse. Perhaps now we face another mysterious turning, in which the countrymen and Faithful who lost their devotion to a certain martyr following the fracturing of Christendom shall rediscover it before its final restoration. Sancte Thomæ Cantuariensis, ora pro nobis.

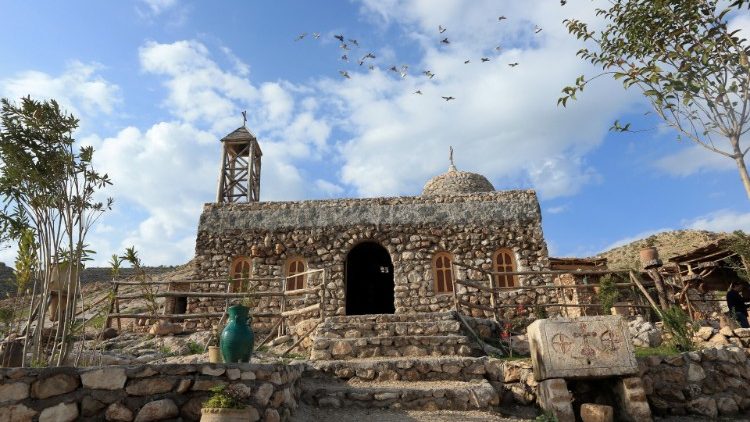

Photo: Richard Burton (1925 – 1984) playing Thomas a Becket opposite John Gielgud (1904 – 2000) as King Louis VII of France during the filming of ‘Becket’ at Shepperton Studios in Middlesex, England, 11 September 1963. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images.)

This article was republished with permission after first appearing in the Gregorius Magnus magazine of Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce, in its Summer 2024 issue.

![]()

The post Why we must recover St Thomas Becket: Catholic England’s standard bearer against secular tyranny appeared first on Catholic Herald.