Economics and the Gospel of Love

January 22, 2026, Vietnam

What every business leader should learn from a Carpenter?

If Jesus were alive today, would He be a socialist, a capitalist, or something worse - a mystic with opinions?

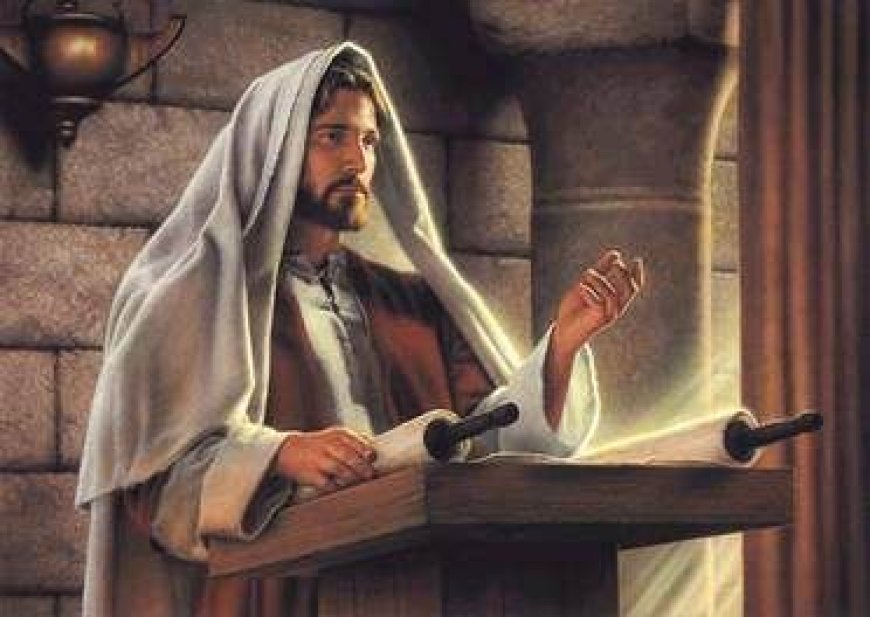

Economists would probably put Him in a conference hall. Bankers might invite Him to Davos. Activists would demand He pick a side. And Jesus, being Jesus, would likely answer with a story about seeds, coins, or lost sheep and walk away smiling.

This is precisely why He is the most unsettling teacher for the business world.

We like neat categories: markets versus morals, profit versus charity, efficiency versus mercy. Jesus prefers contradictions that look like paradoxes but are actually deeper truths. He does not abolish economics; He baptizes it.

Consider the most basic question in business: Why do we work?

The economist says: to earn.

The psychologist says: to feel valued.

The Gospel says: to love.

Already, the accountant is nervous.

Yet the Gospel of Love is not anti-profit. It is anti-greed. There is a difference as vast as heaven.

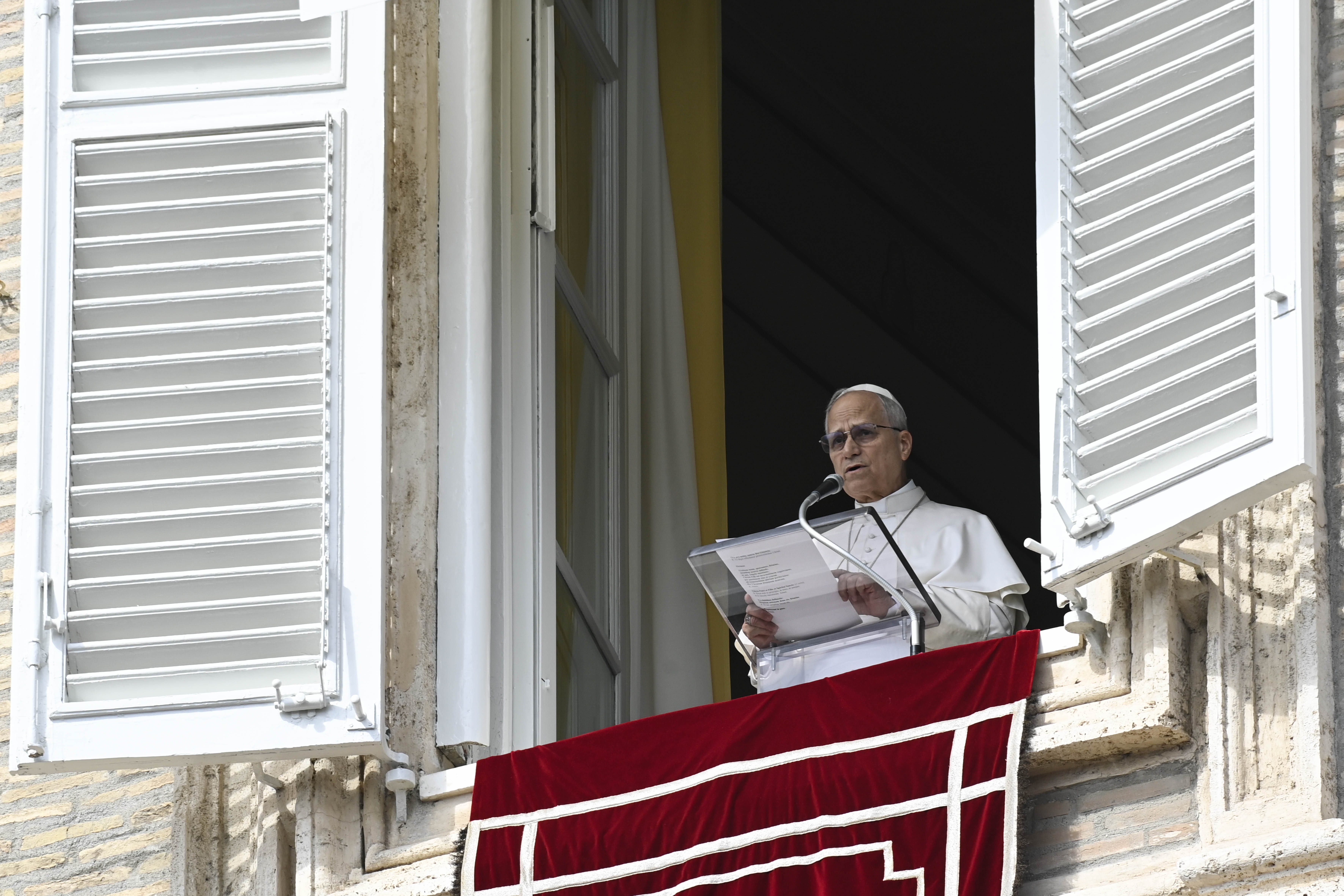

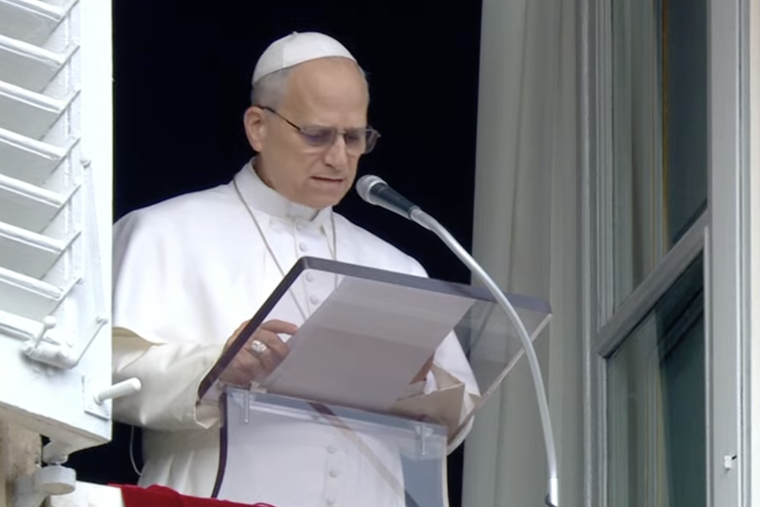

Jesus never condemned wealth itself. He condemned wealth that forgets its purpose. Money is a good servant and a terrible master, which is the best financial advice ever given, though it came from a wandering preacher rather than an MBA.

Imagine Jesus as CEO.

His mission statement would be scandalous: “Maximize love, not returns.”

Shareholders would panic. But perhaps the world would breathe.

In the Parable of the Talents, Jesus actually praises investment, risk, and productivity. The lazy servant is rebuked not for having little, but for doing nothing with it. Christianity, at its best, does not despise enterprise; it dignifies it.

What Jesus challenges is not the market, but the heart behind it.

A business leader shaped by the Gospel does not ask first, How much can I extract?

He asks, Whom does my work serve?

This is not sentimentality; it is sharper than any spreadsheet. A company that serves real human needs with integrity is more economically sustainable than one that exploits people for short-term gain. Love, oddly enough, is good business.

Yet love is costly. It refuses to treat workers as replaceable parts or customers as data points. It sees faces where algorithms see numbers. It hears stories where balance sheets hear silence.

Jesus, the carpenter, knew something every CEO forgets: you cannot build a house if you despise the people who will live in it.

The irony is delicious. Modern capitalism often claims to be “value-neutral,” but the Gospel is unapologetically value-rich. Neutrality, Jesus suggests, is simply an invisible morality pretending to be objective.

If profit is your only god, you will sacrifice people to it. If love is your highest law, profit becomes a tool, not a tyrant.

The cross itself is the ultimate economic lesson: self-gift is the most powerful force in history. No market predicted it. No algorithm optimized it. Yet it transformed the world more than any empire or corporation.

Businessmen often admire efficiency. Jesus admired fidelity. We worship speed; He worshipped truth. We chase growth; He chased holiness. And somehow, paradoxically, societies that take holiness seriously tend to flourish materially, while those that worship material success often rot morally from within.

So what would a “Christlike” business look like? It would pay fair wages not because of fear of lawsuits, but out of reverence for human dignity. It would innovate not only for profit, but for the common good. It would measure success not merely by market share, but by how many lives were made more humane.

That sounds naïve until you realize the alternative is what we already have: economies rich in products and poor in people. Jesus never ran a company, but He understood the human soul better than any strategist. And every economy rests, in the end, on human souls.

Perhaps the real question is not whether the Gospel fits economics, but whether our economics can survive without the Gospel.

The Gospel of Love does not destroy markets. It saves them from becoming machines that devour their own creators.

In the end, the choice is stark and simple — in that biblical way that makes modern people uncomfortable: Either money will serve love, or love will serve money. And history suggests that when love becomes a servant, humanity pays the bill.