How to criticize the Church so it helps, and so you don’t go to Hell

Most practicing Catholics can admit they have struggled with particular decisions or statements coming from Church authorities, or with the perceived priorities of the hierarchy that might seem out-of-step with the life of the faithful “on the ground.”

Loving the Church doesn’t mean being blind to the way she’s in need of reform. Nor does it mean ignoring them. But loving the Church doesn’t mean a kind of destructive criticism either, feeding bitterness, resentment, or rebellion.

So the question becomes clear: how can Catholics of good will, desiring holiness and wishing to see the Church become more holy, engage?

This week some continuing studies gave me occasion to revisit a classic, Cardinal Yves Congar’s “True and False Reform in the Church.”

The book remains unusually relevant.

Written in 1950 and influential for many Council Fathers, including Pope St. John XXIII, the text illuminates the spirit of reform leading into Vatican II, and the perennial question of how the Church discerns and grows. Above all, it offers principles for pursuing reform in a way that actually strengthens the Church’s fidelity to her mission.

Surprisingly, in this reading, the section that struck me most was Congar’s long reflection on “Self-Criticism in the Church.” Writing at the end of a decade marked by a growing prophetic spirit of reform, particularly in France, Congar observed Catholics yearning to find a way to look at the Church and speak about it with a critical eye toward its’ deficiencies, particularly how they concern its’ responsibility to the demands of the Gospel and to the lived experience of those Catholics outside the central “structure” of the Church, those “in the pews,” so to speak.

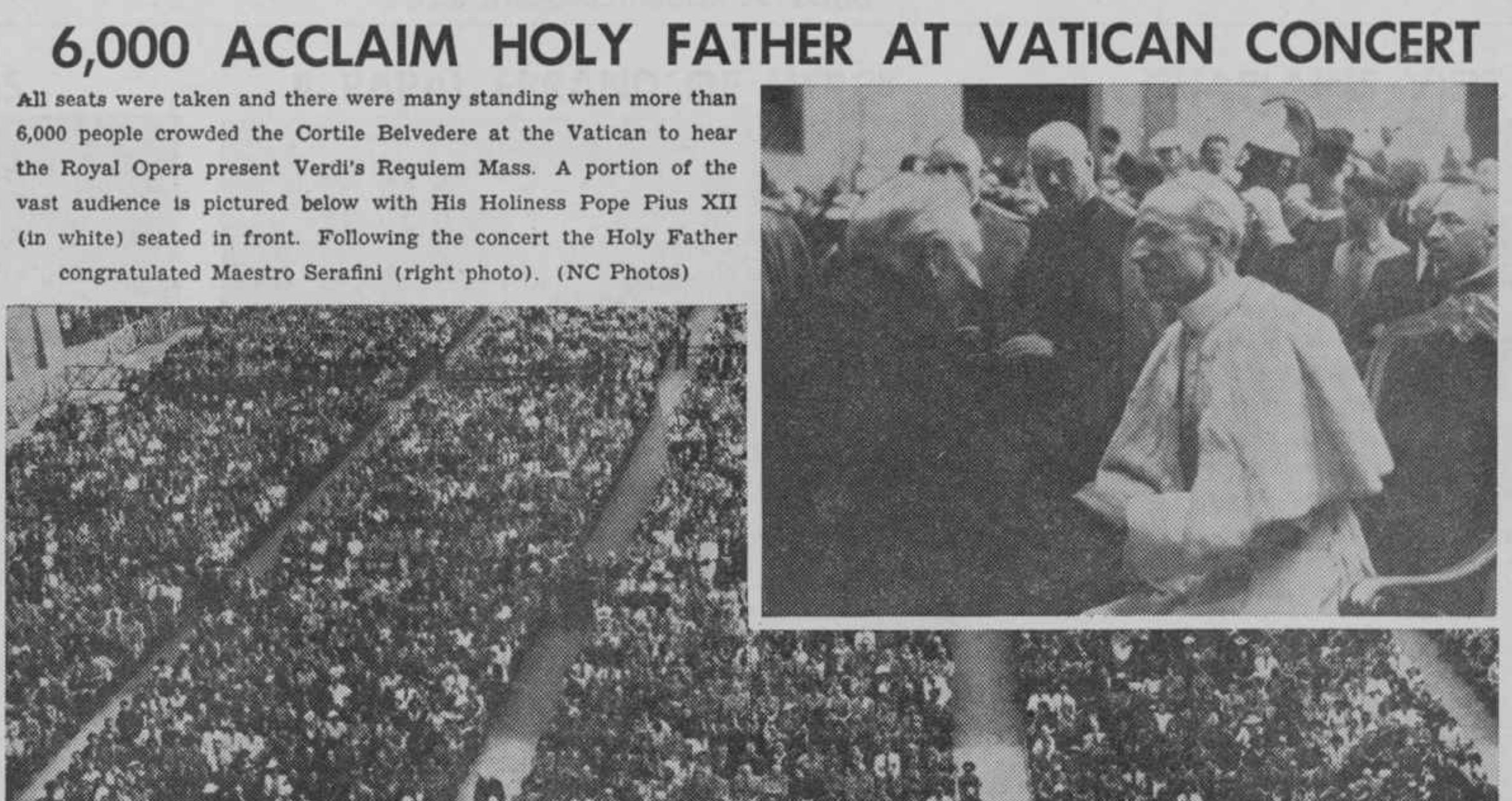

To show the legitimacy of that instinct, Congar quoted Pope Pius XII, “The free expression of one’s opinion is the prerogative of every human society where people, responsible for their personal and social conduct, are intimately committed to the community to which they belong.”

Congar even looked back with a touch of nostalgia at the Middle Ages as a period with a “healthy” capacity for internal criticism. The faithful could speak frankly yet reverently, seeking greater clarity of mission. He attributed this partly to the relative absence of the hostile enemies of Protestant polemics or Enlightenment-era suspicion.

“Being critical, which formerly one could do freely, in good conscience, ‘in-house,’ without diminishing respect for the essentials, became a terrible weapon and the source of attacks that can no longer be controlled or even faced with the candor of previous times.”

Once those external pressures intensified, Catholics grew anxious that internal critique might arm the Church’s opponents. A culture of omertà, silent loyalty, set in.

If Congar feared excessive silence, which still exists, today we often also see the reverse. The prophetic energy for reform has often adopted the tone of contemporary online discourse. Platforms like twitter.com host a daily torrent of “no-holds-barred, go-for-the-jugular” commentary directed at the USCCB, the Vatican, or various bishops. Mediating voices exist, but the tenor of intra-ecclesial debate is sharpening, not softening.

The pain behind this is understandable. Many lay Catholics experience a real tension between their lived discipleship and the perceived priorities or decisions of the hierarchy. But while vitriol and ad hominem reactions may feel cathartic in the moment, they rarely lead to authentic reform and, instead, pose spiritual dangers of their own. That was Congar’s critique of many of his contemporaries, and it applies equally to us.

Many Catholics now find themselves caught between two bad options: Silencing or Skewering.

Considering the long history in the Church of highly effective, prophetic, and reform-minded voices, it is clear there is a virtuous mean to be found, somewhere in between an anti-intellectual placidity characterized by “no action of the Church could ever come under scrutiny for fear of seeming disobedient and divisive” and “lambasting the hierarchy on twitter.com for its every action and inaction.”

Finding Congar’s treatment particularly helpful, and knowing that not everyone has copies of “True and False Reform” lying around, below are four principles for offering criticism that is actually helpful, deeply Catholic, and conducive to our own salvation.

Honor, reverence, and filial respect

As mentioned before, Congar pointed to the Middle Ages as the exemplar of how to criticize the Church virtuously. While noting the criticism was often very direct, and even personal, (he notes Sts. Bernard and Catherine of Siena’s reformist treatises, but also Fra Angelico and Dante’s artistic depictions of certain prelates in agony), he held up what we often lack in our Silencing or Skewering era.

“In that sociologically ‘healthier’ period, a freely expressed critique of individual persons was nonetheless expressed with respect for the ecclesial institution and its functions. Those times did not have any more ‘morality’ than ours perhaps, but they did seem to have a greater ‘code of honor,’ a healthy and solid public spirit.”

Speaking from love of the Church and its mission

“How can Christians live out the absolute sincerity that the Gospel imposes on them if they aren’t able, within the limits of respect for what needs to be respected, to speak about what is most precious to them, the community of the Church?...Let’s stop calling ourselves Christians, if we have to keep still about what Christ taught us.”

I must admit that sentence from Congar rocked me.

My conversations with devout friends after a discouraging experience of the life of the Church, at a Sunday Mass, or in a sacramental preparation setting, proves to me that it is love for the Church that causes pain when the Church is failing.

That same love, not just anger, should drive the way we speak about the need for reform. In prophetically pursuing reform, we are attempting to polish something precious, which has become dimmed, not smash something that is of no value. We ought to be careful and proceed filled with the same love that causes the pain.

For Congar, edification is the goal of reform — building up, not destroying.

Straightforward, courageous and intelligent criticism

In issuing criticism of the Church, Congar cautioned Catholics to be both intelligent, clear, and specific. He cautioned against “covert distractions” conscientious of, “justice and exactitude: refusing loose generalizations, avoiding careless or unilateral judgments, prudence and humility.”

In considering this list, I thought it served as a perfect set of ideas for how to get a lot of clicks on social media.

But real real reform is found on a different path — less viral, and taking more time and effort: frank, measured, theologically precise, and straightforward argumentation, all delivered with the courage it takes to be the contrarian, bearing the personal costs of that truth-telling.

In Congar’s view: “Every spiritual organization that is really alive must encourage genuine critique.”

Criticism for the sake of confidence in mission

Some have noted that in the years following the Second Vatican Council, a culture of self-criticism created, at times, a paralyzed, perpetually self-conscious Church, too aware of itself to be a vital force for spreading the Gospel.

As Chesterton noted, “The object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.” Ignoring the need for reforms is an obstacle to the Gospel. So is being so perpetually aware of the faults of the Church that we begin to navel gaze and lose sight of the reason for reform: greater adherence to the Gospel.

In the spiritual life, we know well the dangers of scrupulosity, a kind of constant obsession with the slightest of one’s faults. If criticism devolves into perpetual introspection, paralysis, or cynicism, it fails. If it leads to a Church more courageous in preaching the Gospel, it succeeds. Reform exists for mission, so that all might come to know the “life and life to the full” that only Jesus Christ can bring, not for endless self-analysis.

The challenges facing the Church today are real, and the polarizations within the faithful are widening. But the only way forward is neither silence nor savagery. We must relearn how to disagree and how to criticize while still pursuing holiness, honoring the Body of Christ, and helping others become saints.

Congar’s wisdom for us is this: Catholic criticism must always be an act of love. Love strong enough to speak truthfully and humble enough to remain honorable.

Anything less will fail to help the Church.

And anything more will harm our souls.