Keep moving, real time, and school ties

The Friday Pillar Post

Pillar subscribers can listen to Ed read this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Happy Friday friends,

It’s still Lent, if you’ve already forgotten and find yourself eyeing the salami in the fridge at 10.30am wondering if that’s what will make you feel a little bit better about the rest of the day.

Something I have always been told about entering the season fully and properly, and not settling into a period of more-or-less muted everyday life, is the spirituality of moving. Our Lenten disciplines are meant to shake us out of our routine, rouse us from spiritual torpour, and remind us that the hour is already late.

God, when He comes, comes always to put us in motion — whether it is the people of Israel in the great Exodus narrative, or Christ himself being led by the spirit into the desert. Ours is a God who meets us on the move, calling us from where we are to something better, leading us on the strength of His promise.

Lent is the season for spiritual dynamism — for doing and going, for change, for heading to Easter through a time in which we trust God will orient our progress towards Him and the resurrection.

Of course, what we can’t or won’t do for ourselves the Lord often does for us, because he loves us. This is the spirit in which I have been trying to grapple with some domestic unease these last few weeks, with our landlords giving us notice that they are planning to sell our house either to us, or out from under us, probably soon, maybe.

I don’t react well to uncertainty and, having moved on average every four and a half years of my life, the idea of having to do so again fills me with a special kind of ambient existential dread, especially since we’ve just about put down some roots in our neighborhood.

I react even less well to debt and risk, of course, so driving hard at the prospect of a first mortgage in an unstable economy as the lesser of two unappealing options carries its own calls to prayer.

The whole situation is a reminder to me of the temptations Christ faced in the desert, the first of which is to doubt that God is a loving father who sees and knows all that my little family requires. Prayer in these moments is a reminder to trust in Him, and to remember first and always that it is He not me who answers our needs.

Wherever we find ourselves come Easter, I know that I will have special cause to bless the Lord for leading us there. Whether I can bless Him with confidence along the way is my special Lenten challenge, at least this week.

Here’s the news.

The News

The bishops of the Philippines have said the time has come for the country’s former president to face the consequences of his actions, following his arrest for crimes against humanity.

While angry Duterte supporters converged outside of the military air base where the former head of state was temporarily detained, the Catholic country’s bishops weighed in on the arrest.

Bishop Jose Colin Bagaforo, who chairs bishops’ commission on social action, justice, and peace, said: “True justice is not about political allegiance or personal loyalty — it is about accountability, transparency, and the protection of human dignity.”

“For years, former President Duterte has claimed that he is ready to face the consequences of his actions. Now is the time for him to prove it.”

He’s just one of several bishops who have weighed in on the arrest and the controversial legacy of the former president.

—

The Vatican this week launched a full court press against reports that an Argentine political activist had attempted to break into Pope Francis’ hospital room to see the pope.

With the pope set to enter his second month of hospitalization, there has been no shortage of online fake news and conspiracy theories surrounding his convalescence. But few of them have merited a formal slap down from Vatican media, still less a personal letter from a curial cardinal.

What, then, made a story about Juan Grabois different?

Well, it turns out he’s a rather fascinating figure, with personal ties to the pope stretching back years and formal links to the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development.

—

According to the bishop responsible for its care, the Diocese of Steubenville has enough money and enough priests to continue its mission.

As we reported earlier this week, Bishop Ed Lohse, apostolic administrator of the Ohio diocese, issued a report on its current state and long-term viability amid continued chatter about a long-mooted merger with the neighboring Diocese of Columbus.

Yet, despite some actually pretty reassuring headline findings, Lohse remained more bearish than bullish about Steubenville’s future, warning especially about regional demographic trends.

You can read the whole analysis here.

—

The installation of Cardinal Robert McElroy as the eighth Archbishop of Washington went off with a bang on Tuesday.

Has, against all the odds, the appointment of Cardinal McElroy — ordinarily a rather contentious, not to say divisive figure amongst his brothers — managed to unite the bishops?

Well, for a couple of reasons, I think maybe it has.

—

An Iowa priest has pled not guilty to criminal theft, after he was arrested last month on charges of stealing $164,000 from his rural parish.

Fr. Tom Thakadipuram, 61, was arrested last month and charged with seven criminal counts, after investigators found he had illicitly transferred parish money to his own bank accounts, using a fake missionary organization as a cover. Investigators say that when police approached him about the theft, he attempted to close some personal bank accounts and transfer the money elsewhere.

The most recent theft was in January, according to court records.

An expert in parish theft says the arrest is a reminder for dioceses to set clear policies about financial management, and to audit compliance regularly.

—

It is a cliche to say that the next Catholic scandal in the Church will be financial.

But even as attention grows on incidences of theft in parishes and other Catholic institutions, the issue has received little national discussion among bishops, and little public conversation about developing particular law or policy to curtail the issue.

As JD pointed out in an analysis this week, the tools for the detections and prevention of financial crime in the Church are all getting better, but there is not — as yet — any real sense of urgency or even interest in seeing them deployed across the board, or in sharing best practice.

If financial crime is the “next big scandal,” do the bishops need a Dallas Charter on money problems to deal with it, JD asked?

I think the answer is obvious, but you should read the whole thing.

Real time

Just one note from me on the same issue.

We have amassed a whole catalogue of coverage dealing with, broadly speaking, ecclesiastical financial crime, including this week’s story about Fr. Thakadipuram.

Sometimes the people involved in these stories are clerics, but almost as often they are lay Catholics working for the Church in some capacity. Sometimes we are talking about hundreds of millions of dollars (or euros), reaching up to the top of the Vatican, but more often we are dealing with six figure crimes at the parish level.

Sometimes people go to jail, sometimes Church authorities decline to press charges, or they plead for leniency.

And sometimes we get notes from readers asking us, basically, what’s the point of covering these stories — they’re all sad, discouraging instances of human failure, but nobody got hurt, really. It’s only money, after all, etc. Can’t we just give it a rest?

So, the point I want to make about all this coverage is: we aren’t doing it out of morbid curiosity or to rubberneck at scandal. And discouraging it may be to read; it’s not the most enjoyable thing to write about either. But these stories do matter, and they form a constellation making up a much bigger story that matters a very great deal indeed.

And ignoring the signs of a big problem spread throughout the society of the Church is something we have some experience with, and it is not good.

For decades, following the Spotlight revelations, it has become, as JD noted this week, a trite truism to say that “the next big scandal” to engulf the Church will be financial.

What our coverage of this shows — and the reason we are covering it wherever we see it is — this isn’t the next big scandal that will come. It is here. It is happening now, we are watching it unfold in front of us in real time, and the Church is counting the cost of it all.

The question is whether the Church will turn its attention to addressing it with the same kind of common resolve and seriousness with which it confronted the last big scandal.

But if it is going to do so, the bishops will have to be proactive, there will be no mass campaign of public outrage that the Church is being swindled into a slow and steady insolvency by large scale petty crime, even as so many dioceses are battling bankruptcy and fighting to keep the lights on in parish churches and schools.

As JD wrote in his analysis, “While many dioceses have made strides toward auditing and identifying financial misconduct, bishops rarely use the criminal and canonical tools available to them to see perpetrators punished. And that reality diminishes the deterrent for clerics or employees tempted toward theft to think again.”

I totally agree. The need for some kind of holistic approach and common recognition of the problem is obvious and urgent. But, honestly, I am not immediately hopeful that we will see much in the way of action.

I hope, though, that I am proven wrong.

School ties

As many of you know, I was mostly educated in England, where I went to one of those kind of schools which inhabit the American popular imagination as somewhere between a Lord of the Flies system of structured brutality, and Harry Potter.

Private school, basically. Or public school, as it is called over there.

My own school wasn’t a boarding establishment, though it had many of the hallmarks of “traditional” English boys’ schooling.

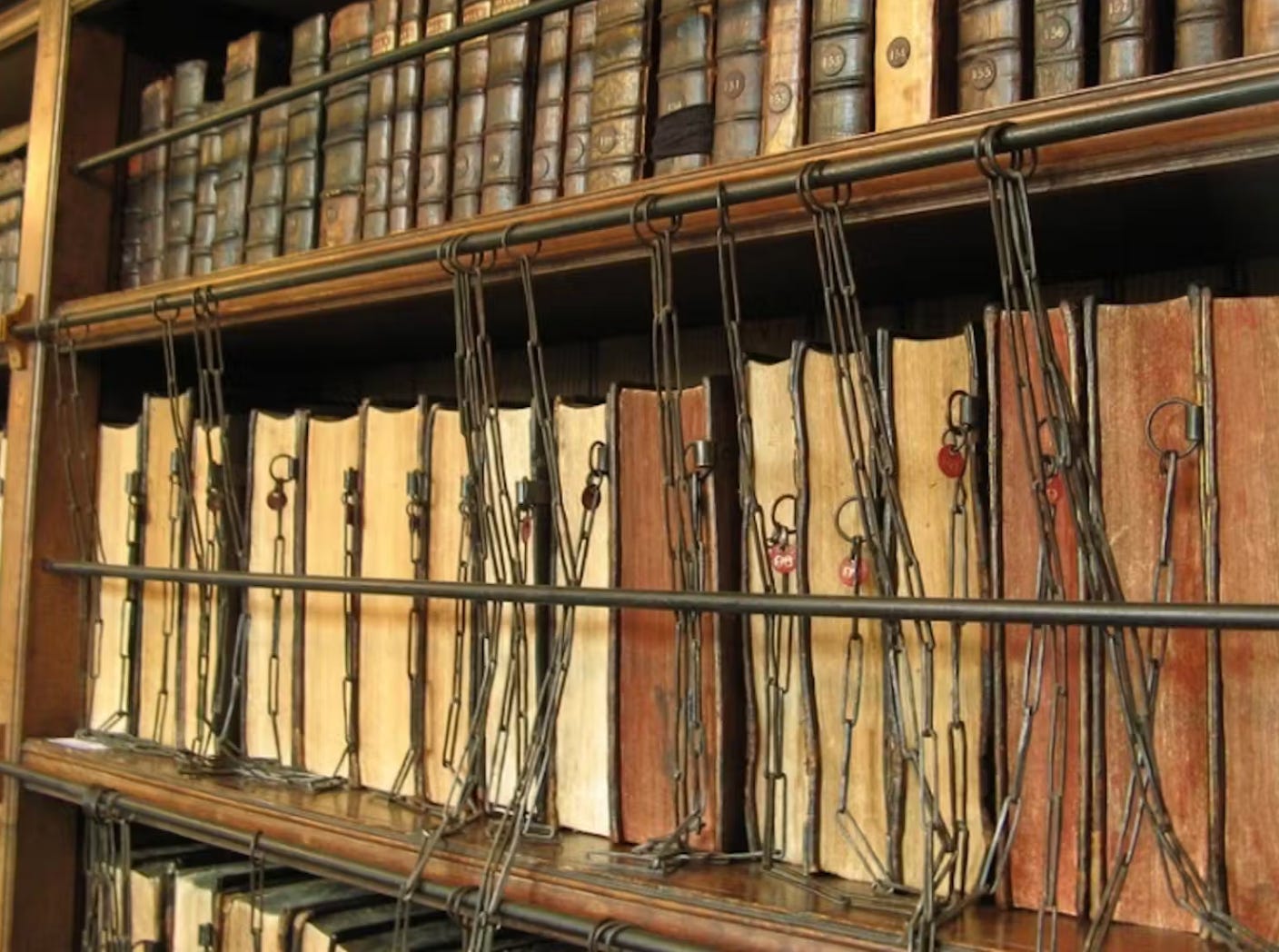

It was founded nearly a century before the city of Boston, the headmaster reigned in remote dignity from a monastic-era library where the books were individually chained to the shelves, we were sorted into houses, and teachers took great care to individualize their criticism — academic and personal — with enough rhetorical sharpness that each and every student truly felt “seen,” as they say these days.

For this reason I’m fascinated by the pop culture presentation of the American high school experience, at least as it was for my generation, with its co-ed cliques and socially segregated lunch tables, homecoming dances and febrile dating scenes. It’s a very different world from the one I knew, in which the principal dining hall distinction was that the senior rugby team lunched on an elevated stage above the rest of us.

It wasn’t all bad, of course. I adored my two history teachers.

One blended a genius for sarcasm at trivial mistakes with such sincere personal concern when you actually screwed up that he left you feeling genuinely cared about.

The other, a distracted, ink-stained anachronism of a man, would spend double lessons delivering himself of lengthy, furiously animated lectures we were to take down as dictation, excusing himself for a break halfway through to “collect some photocopying” — though we could all see across the courtyard into his office as he spent five minutes sucking on his briar pipe like a drowning man handed an air hose.

Those bright spots aside, though, I hated the place. Every living minute of it.

The halls were patrolled by the vindictive scrappings of the senior class, empowered by their status as prefects to dole out arbitrary punishment on the rest of the student body for crimes as obscure and specific as “looking insolent” and “breathing ridiculously.”

I was assigned detentions for both those offenses by a particular upperclassman who decided soon after my arrival that he didn’t like the look of me.

Or maybe he did.

He took it out on me either way, stalking me through the halls every break time looking for (or inventing) any excuse to write my name in the malefactors’ book in Room F01, where the deputy headmaster, whom we referred to as “Maximum Bob,” brooded like a malevolent weather front.

And, to be fair, I became equally inventive over the years as I came to embrace my designation as a bad seed.

Despite priding itself on its forward-thinking (for the mid 1990s) “pastoral approach” to education, the place rightly enjoyed the reputation as being something of an exam factory.

Students were relentlessly assessed, sorted into aptitude streams, and drilled to pass the biannual slate of exams which constituted your validation for continued existence. Those who slipped too far below the expected standard of straight As were invited to consider furthering their education elsewhere, as I was at the age of 16.

But, as Evelyn Waugh observed, the thing about the English public school system is, “they may kick you out, but they’ll never let you down.” He wasn’t wrong.

Despite my designation as an “academic lightweight” (I actually have that in writing from the headmaster), I successfully traded on the relative prestige of having attended the place at all to shameless advantage at every stage of my later scholastic career.

And however many pages my name and crimes consumed in the deputy head’s big black book of bad boys, the lessons I learned about the reality (and relative justice) of arbitrary standards and authority prepared me for adult life in ways I still benefit from.

All this came to mind this week for me when I read the newly-published annual school league tables by which the place, teachers and students, lived and died. I felt, to my surprise, a real pang of reflexive sadness that my alma mater had crashed out of the top 25, well below the acceptable floor for performance, and barely clung on to a best 50 ranking.

I’ll never remember the place fondly. And, had I a son, I would sooner turn him loose in the woods with a good book and a sharp knife for eight hours a day than send him there.

But as Waugh had it, they may have kicked me out, but they never let me down. And they never really let me go, either.

See you next week.

Ed. Condon

Editor,

The Pillar