Living Corpus Christi in a Liturgical Desert

I will attend only the TLM or another traditional rite of the Church.

Vigil of Corpus Christi

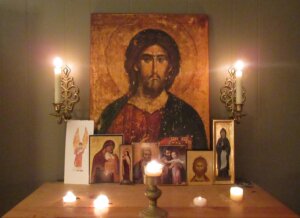

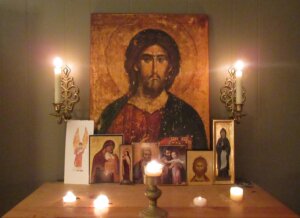

Photo: Dr. Kwasniewski’s icon shrine where he prays the Divine Office. Courtesy of author.

This week the Roman Rite celebrates the Feast of Corpus Christi, a deliberate echo of Holy Thursday, on the first available Thursday after Paschaltide. The feast traditionally lasts for eight days, as indeed Our Lord presupposed when he asked St. Margaret Mary Alacoque for the institution of a feast of reparation on the day after the octave, which became the Feast of the Sacred Heart. All who love the venerable Roman Rite should therefore strive to celebrate its octave as well, one of many pre-55 practices that are ripe for restoration.

A feast like this can occasion doubts and difficulties for the faithful. Corpus Christi is often arbitrarily transferred to the following Sunday, making this Thursday a deflating feria. (Note, this is not the same as the traditional practice of an “external solemnity,” whereby a great feast, celebrated on its proper day, is then permitted to be repeated once on the nearest Sunday.) In certain places, the TLM has been abolished thanks to an unnecessary draconian implementation of Traditionis Custodes. In still other places, the Mass options are mostly or even uniformly offputting. Some bishops have even tried to prevent the Novus Ordo from being celebrated in a more traditional manner compatible with its rubrics!

Don’t Guilt Yourself about Daily Mass

Given such a situation, the question has become pressing for many: Should I go to a daily or weekday Mass “no matter what,” or should I attend Mass only when it is celebrated in the usus antiquior? This is no merely speculative question. The question has been posed to me many times, in person or via email. Here’s a representative sample:

I love Holy Mother Church and I know that the Ordinary Form is valid and licit, but it is simply inferior and not the ideal. I can only attend an Extraordinary Form on Sundays, not weekdays, and so I wonder: is it better if I attend weekday low Masses in the Ordinary Form, or is it better if I follow along with the FSSP LatinMass.net and receive spiritual communion?

I struggled with this question for years before coming to my present position, namely, that I will attend only the TLM or another traditional rite of the Church. The matter is in the realm of prudence: there is no clear-cut black-and-white answer to it, and the answers may vary depending on circumstances. There are, however, fixed principles we can use for deliberating.

One principle is that assistance at weekday Mass is meant to be beneficial for our souls, so we should not believe that we are obliged to attend a Mass if it is going to be spiritually disturbing, take away our peace, tempt us against charity, or otherwise set us back in our spiritual progress. St. John Henry Newman wisely wrote in a letter on January 14, 1865: “It is no sin to feel it difficult to accommodate your mind to certain things, and it is better not, in the way of devotions, to force yourself at all.”[1]

Another principle is that assistance at Mass in person is preferable to watching a broadcast Mass, for the liturgy is a bodily reality and our bodily presence is intended as part of the sacrifice we offer up to the Lord. All things being equal, going to church is superior to watching church; yet it is seldom the case that all things in fact are equal. A lot will depend on what kind of Mass is available to you on weekdays. Is it reverent and prayerful? Is it irritating and banal and distracting? These are questions only you can answer, being on the spot. My article “Sorting Out Difficulties in Liturgical Allegiance” may help you with your discernment; I won’t repeat here the advice given there.

Why Frequent Communion Is Good

Another principle is that, provided one is in a state of grace, reception of Holy Communion is better than a spiritual communion, since it unites us body and soul to the fleshly and divine reality of the Lord, as opposed to uniting us in intention and desire, as a spiritual communion does. On this point, there has been much discussion and considerable confusion, with some traditionalists nowadays questioning the wisdom of Pope Pius X’s encouragement of frequent communion.

There is, however, no reason to question the practice, which was defended by many holy people for centuries prior to Pius X. For example, Mother Mectilde of the Blessed Sacrament (1614–1698), foundress of the first religious community to be dedicated to perpetual Eucharistic adoration, writes to a laywoman, the Duchess of Orléans, at a time when Catholics often abstained from Holy Communion for long periods of time:

Start, and never stop, receiving Communion on all Saturdays and feasts. I will never have any consolation unless I see your soul possessing this holy practice, whatever favor you show me by honoring me with your friendship. I ask it of you with as much earnestness as someone ambitious for the highest good fortune. And I dare to say that I am asking it on behalf of my God who desires this of you. He desires to come to you and nevertheless you do not receive Him. You have many small weaknesses that will only be eradicated by availing yourself of this Eucharistic bread. Why deprive your soul of an infinite good? Listen to the voice of this adorable Savior who calls from your heart’s depths: “Aperi, aperi mihi, soror mea, sponsa mea…. Open to Me, open your heart to Me, My sister, My bride, My beloved, that I may make My eternal dwelling in it and take My rest in you.” He wants to be united to you, to make you entirely one with Himself. Do not refuse what the angels consider themselves infinitely blessed and unworthy to receive. Surely, if you do not listen to this divine voice I will be a thousand times more aggrieved than if I was condemned to death. I see the moments passing, the weeks and months, and that, because of I do not know what temptation, you are delaying your eternal happiness. I beg you not to go on any longer like this, for fear that, when you desire to receive Communion, you no longer can: and in the meanwhile you are depriving your soul of the divine life.[2]

Making allowances for the grandiloquent manner of the Grand Siècle, Mother Mectilde’s essential advice is as sound as ever.[3]

Your Catholic Instincts Are Right

Above all, don’t give in to the notion that it’s only a matter of “personal preference” (and, therefore, purely subjective) on your part to seek out Communion on the tongue and kneeling, Latin and chant in the Mass, ad orientem, the Roman Canon, etc.; these things are objectively better, based on the powerful witness of centuries of Church tradition, with rational arguments to back them up. Even if the opposite of all these things is “permitted” nowadays, that does not make it any less irreligious in the broad sense, lacking in devotion and piety and fittingness.

Moreover, the assertion some make—that we should “offer up our sufferings at Mass”—is true if one is talking about the crosses God sends us in life, which should be placed on the paten together with the host: a physical debility or sickness, a family crisis, hardships at work, trouble with friends, anxieties and stresses of all sorts. The liturgy itself, however, is not supposed to be one of those crosses! Rather, it is our privileged encounter with the Crucified and Risen Lord, so it should be a time of strengthening and nourishment, of building up the interior man. If it’s not doing this consistently, it’s failing to benefit the ones for whom Christ instituted it. Nor can it be maintained that embracing a badly celebrated liturgy is a form of asceticism or detachment.

As far as Sundays and Holy Days go, we are required to attend Mass, and here it may be worthwhile to travel some distance to find a TLM (or, in lieu of it, a traditional Eastern rite). But on a weekday, given all that has been said above, it can often be better to stay home and meditate with a missal, pray a portion of the Divine Office (such as the hour of Prime), or do lectio divina with Sacred Scripture, if one can find a quiet place and set aside some time for it, as we should be trying to do in any case, since daily prayer is part of the daily bread that will keep us spiritually alive. Although receiving Communion every day is ideal, it is not the only factor to be taken into account. The corruption of the liturgy is a tragic fact of our times, and it really does change the “calculus,” so to speak. If we are thrust into the desert, we should do the sorts of things the desert fathers and mothers did, who, in some cases, had only rare access to the Eucharistic liturgy.

Learning from the East about Mass-free Days

In recent decades the Latin-rite Church has often expressed its desire to allow “light from the East” to enter into our awareness and to illuminate us with the wisdom it has to offer. (I sincerely believe that the East would also benefit from admitting in some of the traditional light of the West, but that’s a different article for another time.) One fruitful concept from the East would be that of “aliturgical days,” which doesn’t mean a day on which there is no liturgy whatsoever—the psalms are always prayed daily, as in the West— but a day on which there is no Divine Liturgy, i.e., no Eucharistic Sacrifice. On such days, all Eastern Christians perforce are fasting from Holy Communion.

In the decadent Western Church of today, we could apply the concept of “aliturgical days” to the many days of the year when the traditional Roman Rite is not offered in a given place and where there is no other tolerable substitute for it. In such places, we are deprived not through our own fault, but by God’s inscrutable will, which allows an evil of privation through which we may deepen our longing for the Holy Sacrifice and for Holy Communion, and redouble our prayers for the full restoration of tradition.

None other than Joseph Ratzinger made a bold suggestion:

Do we not often take the reception of the Blessed Sacrament too lightly? Might not this kind of spiritual fasting be of service, or even necessary, to deepen and renew our relationship to the Body of Christ? The ancient Church had a highly expressive practice of this kind. Since apostolic times, no doubt, the fast from the Eucharist on Good Friday was a part of the Church’s spirituality of communion. This renunciation of communion on one of the most sacred days of the Church’s year was a particularly profound way of sharing in the Lord’s Passion; it was the Bride’s mourning for the lost Bridegroom (cf. Mk 2:20).

Today too, I think, fasting from the Eucharist, really taken seriously and entered into, could be most meaningful on carefully considered occasions, such as days of penance—and why not reintroduce the practice on Good Friday? It would be particularly appropriate at Masses where there is a vast congregation, making it impossible to provide for a dignified distribution of the sacrament; in such cases the renunciation of the sacrament could in fact express more reverence and love than a reception which does not do justice to the immense significance of what is taking place.

A fasting of this kind—and of course it would have to be open to the Church’s guidance and not arbitrary—could lead to a deepening of personal relationship with the Lord in the sacrament. It could also be an act of solidarity with all those who yearn for the sacrament but cannot receive it. It seems to me as well that the problem of the divorced and remarried, as well as that of intercommunion (e.g., in mixed marriages), would be far less acute against the background of voluntary spiritual fasting, which would visibly express the fact that we all need that “healing of love” which the Lord performed in the ultimate loneliness of the Cross.

Naturally, I am not suggesting a return to a kind of Jansenism: fasting presupposes normal eating, both in spiritual and biological life. But from time to time we do need a medicine to stop us from falling into mere routine which lacks all spiritual dimension. Sometimes we need hunger, physical and spiritual hunger, if we are to come fresh to the Lord’s gifts and understand the suffering of our hungering brothers. Both spiritual and physical hunger can be a vehicle of love.[4]

Concerning that Good Friday Eucharistic fast, a priest of the Fraternity of St. Peter once explained to me that the Gospel readings over the two weeks after the Transfiguration on the Second Sunday of Lent depict in several instances a withdrawing of Our Lord from our presence, which seem to be something of a preparation for His complete withdrawal from our presence on Good Friday—hence the fittingness of the fast from Holy Communion itself. When He is taken from the land of the living, He is gone. We know He is not absolutely gone (ever), but we enter into His dereliction, death, entombment, silence, and physical unavailability.

The Need for a Restored Eucharistic Fast

This brings me to the related question of the Eucharistic fast. The reduction of the fast to a single hour before receiving Communion was a dramatic mistake, as serious Catholic commenters now seem to acknowledge as a matter of course. This, too, could be a matter for a certain examination of conscience.

If we receive frequently, are we taking sufficient pains to prepare ourselves, to be not only in a recollected frame of mind but also a hungry, empty state of body suitable to this great moment of encounter with the Lord God of heaven and earth?[5] In a passage from He Leadeth Me that has power to shock us from complacency, the American priest Fr. Walter Ciszek talks about his clandestine Masses at a forced labor camp in Siberia, at which everyone observed the traditional Eucharistic fast from midnight:

Most often… we said our daily Mass somewhere at the work site during the noon break. Despite this added hardship, everyone observed a strict Eucharistic fast from the night before, passing up a chance for breakfast and working all morning on an empty stomach. Yet no one complained…. I would go to any length, suffer any inconvenience, run any risk to make the bread of life available to these men.[6]

And a little later in the narrative he writes:

All of this [trouble to say Mass far from the guards] made it difficult to have many prisoners in attendance, so we would consecrate extra bread and distribute Communion to the other prisoners when we could. Sometimes that meant we would only see them when we returned to the barracks at night before dinner. Yet these men would actually fast all day long and do exhausting physical labor without a bite to eat since dinner the evening before, just to be able to receive the Holy Eucharist—that was how much the sacrament meant to them in this otherwise God-forsaken place.[7]

What a reproach to us lazy modern Westerners, for many of whom even the mitigated fast of Pius XII—three hours before Communion—would now seem an almost heroic task!

Why do I mention this? Simply to underline that there are ways in which we can make our Communions “count for more,” especially if they will be fewer in number. One of those ways is to willingly embrace both the sacramental fasting of aliturgical days and the traditional midnight or three-hour fast prior to reception. In this way, we will be more conscious about what we are doing, more deliberate, which, over time, will have the effect of making each Communion more intensely anticipated and appreciated.

How Tradition Sustains Us in the Desert

The traditional Roman liturgy helps us a great deal in this regard, both because it moves more slowly, more deliberately, toward the pinnacle of the Mass in the consecration, and because it prepares us more thoroughly for Holy Communion and allots more time for coming down from the mountain. It places us in a receptive and meditative frame of mind (except when small children prevent it or shatter it, God bless the clueless darlings!), and seems to penetrate more fully into our being. I’ll never forget the comment that a friend of mine once made, as we were talking about why we didn’t go to daily Mass sometimes—as long as we had the Sunday TLM: “It has so much depth and power, I find that it lasts me all week.”

It lasts me all week. That is how Sunday Mass is meant to be experienced, whether or not we have access to daily Mass in addition. When the Church rediscovers the secret of her youth, the secret of tradition, she will begin to see a reversal of the endless attrition, the soft apostasy, that is thinning out her congregations everywhere and forcing church closures under grimly cheerful names like “All Things New.” The biting irony is that it is precisely All Things New that paved the way to this cemetery of churches.

The “abundance of life” Our Lord came to share with us—the life of His Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity—always included, from the start, the life of His people, His Church, unfolded in her tradition, where the “fullness of truth” is at home. Him we will find at home in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, upon the altar of stone, in the ornate tabernacle of gold, yet also within His preferred dwelling—in the host of our hearts, the lunette of our love, the monstrance of our minds—and He will then accompany us into the street. He is Emmanuel, God with us, and we may and must adore Him, whether or not He receives the public veneration on Corpus Christi that He absolutely deserves and that we long to give Him.

Read more of Dr. Kwasniewski’s work by joining him at his Substack “Tradition & Sanity.“

[1] To Lavinia Wilson, Letters and Diaries XXI:387.

[2] This is from a recently released first-ever English translation of the correspondence between the two: see My Kingdom Is in Your Heart: Letters to the Duchess of Orléans and Meditations on Christian Life (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2023), 20.

[3] For a more thorough treatment of this question, see “Tensions in the Catholic Tradition on Frequent Communion.”

[4] Joseph Ratzinger, Behold the Pierced One: An Approach to a Spiritual Christology, trans. Graham Harrison (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986), 97–98.

[5] I am excluding, of course, pregnant and nursing mothers from this advice: the Lord has placed another human life in their immediate care, totally dependent on them and draining them of the extra energy they might otherwise have for something like a midnight or three-hour fast. Such women are already making sacrifices with their body; fasting need not be added on top of the others.

[6] See Walter J. Ciszek, SJ, with Fr. Daniel Flaherty, SJ, He Leadeth Me [1975] (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 126–27.

[7] Ibid., 130.