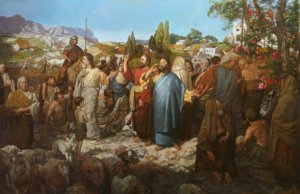

Many are Called, but Few Are Chosen

It has been quite a liturgical ride over the last few weeks, with Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi, coincidental Sacred Heart and Nativity of John the Baptist. Coming up in Rome, where I write this entry, will be Sts. […]

It has been quite a liturgical ride over the last few weeks, with Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi, coincidental Sacred Heart and Nativity of John the Baptist. Coming up in Rome, where I write this entry, will be Sts. Peter and Paul, which shuts everything down here for reasons that are obvious. On this Sunday, however, we are back in the color of hope, green for the 2nd Sunday after Pentecost. These green post-Pentecost Sundays will march us all the way to the end of the liturgical year and the beginning of the next with Advent at the end of November.

Apart from the great cycles of Advent through Epiphany, and Pre-Lent through Pentecost, we mark liturgical time with “green” Sundays after Epiphany (until Pre-Lent) and more numerous Sundays after Pentecost (until Advent). In the Novus Ordo calendar these two sets of green Sundays are conceived as one season, interrupted by the Easter cycle, and it sadly has come to be called “Ordinary Time”, though “Ordered Time” would be more accurate. In any event, it should not be thought of as “unimportant time”. It seems that the idea behind the Novus Ordo “Ordered” Sunday was that it was supposed to be just Sunday, that is, without the added themes of Advent/Epiphany and Lent/Pentecost piled on top of them. They were to be thought of as the Lord’s Day pure and simple. I don’t know how successful that was. One witty cleric of my acquaintance, now gone to God, used to called “Ordinary Time”, divided as it is, “Greater and Lesser Meatloaf”.

This doesn’t mean that the Sundays after Pentecost are not organized and divisible into sections. One of the great writers of the 20th centuries Liturgical Movement, Pius Parsch (+1954), a Canon of Klosterneuberg, broke down the entire liturgical year, Sunday by Sunday, feast by feast, with history and devout meditations in a series called The Church’s Year of Grace. Here is how Parsch brings us into the Season after Pentecost, in which he identifies three themes. A longer quote is worth our time:

The first [theme] is Baptism and its graces. We are baptized and grounded in the graces of Baptism. Every Sunday is a reminder of Baptism and a small Easter.

The second theme is preparation for the second advent of the Lord. It is treated in detail on the final Sundays of the season.

The remaining theme, the burden of the Sundays midway after Pentecost, may be summarized as the conflict between the two camps. Although we are placed in the kingdom of God, we remain surrounded by the kingdom of the world. Our souls are laboring under Adam’s wretched legacy and waver continually to and fro between two allegiances.

By these three great themes the liturgy covers the whole range of Christian life. In Baptism the precious treasure of the Spirit was conferred. Through it we are God’s children and may call God Father. Through it we have become temples of the Holy Spirit, heirs and brothers of Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, Baptism has not translated us to a paradise without toil or trouble. Rather, we are sent out into a troubled world to work and struggle. We must guard the holy land of our souls against hostile attack. We must learn to know and conquer the enemy, and such is the task that will continue until we have taken our final breaths.

The Church serves as both the heroine, who teaches us the art of warfare, and our strong fortress and shield in the conflict. Through Holy Communion, she bestows aid that repeatedly frees the soul from the entanglements of temptation. How does she do this? Courage and strength and perseverance flow from the Word of God in the Service of the Word, and they flow in even fuller measure from Holy Communion. Of ourselves we are helpless creatures, wholly unable to withstand the attack, but in Holy Communion. Another battles for us. The Mightier, Christ, vanquishes the mighty. By means of Holy Communion, we are enrolled in our Captain’s forces. And thus Christ’s battle becomes our battle and His triumph our triumph, and His wondrous strength renders us invincible.

With that as background for the season, let’s turn to the Gospel for Sunday, which is the Parable of the Supper from Luke 14.

The context of Luke 14 is that Christ went, on the sabbath, to eat at the house of an important Pharisee. Everyone “was watching him”. Suddenly someone with dropsy, swelling of tissues with water probably from congestive heart failure, was there, which seems like a set up, a trap. Christ healed him, which was “illegal” to do on the sabbath because it is a kind of work. Christ then taught about humility and hospitality and gave a parable, our reading from the Gospel today, about a “great dinner”.

A great lord wills to hold a great banquet. He invites many different people from various walks of life. They all decline the invitation with various excuses. One that we all become familiar with as we grow up and get out on our own and our friends marry: ‘I have married a wife, and therefore I cannot come.’ However, in the parable, this was not just a guy inviting buddies to an evening barbeque and ballgame, but a great lord and a banquet. He is quite angry. He orders his servants to go into the streets and pull in everybody so that the banquet will be filled.

Remember that parables have twists in them. The first twist is that it is unlikely that people would refuse to come. The second is that the lord would bring unknown people in. But that is what happens in the workings of grace and salvation, isn’t it? God invites us to something lavish, His love, Heaven. Many refuse. Just as the Jews had refused God’s prophets and many would refuse Christ’s Apostles, God’s saving work expanded to all the peoples of the world, not just His chosen people.

The parable in Luke 14 has a parallel in Matthew 22 about the king who held a wedding feast for his son. It can help us understand better the parable in Luke.

In Matthew, a king invited many who not only refused but also killed the messengers. The angry king responded by destroying their villages. Thereafter, as in Luke, people were brought in from the streets. The Matthew version includes something Luke’s does not. Someone who came into the wedding feast didn’t have the right king of wedding garment. The king commanded,

‘Bind him hand and foot, and cast him into the outer darkness; there men will weep and gnash their teeth.’ For many are called, but few are chosen. (vv. 13-14)

The king is God the Father, the son is Jesus and the originally invited guests are the Jews, who attacked or ignored the prophets God sent, as many would also refuse Christ and the Apostles. They are destroyed, perhaps a foreshadowing by the Lord of the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 AD. The other peoples, Gentiles are brought it.

But what’s with that wedding garment and the outer darkness?

First, it helps to know that, in Matthew, it is a wedding banquet. While weddings are everyday occurrences, a royal wedding is not. People don’t refuse those invitations. And they don’t kill the messengers, which is a twist. Another twist is the savage response of the king. Yet another is that after dragging people in, the king throws a guy out for not being dressed properly, and not just out of the palace but “into the outer darkness” which is the way that ancient Jews described the place of the damned in Hell, Gehenna. Also, the fact of a nuptial feast hearkens back to the description of the Messianic Banquet in Isaiah 25, which is a sacrificial feast which will “swallow up death forever, and the Lord God will wipe away tears from all faces”. This isn’t just a normal wedding. It isn’t just a regular garment.

Let’s stick with Matthew a little longer. In the Old Testament, garments could mean various things, for example, you can be clothed in deeds of righteousness. A garment can symbolize God’s favor or even the glory of Heaven. St. Gregory the Great (+604) sees the garment in this parable as being love.

It is possible to go into something sort of half-engaged. So too, one can have faith and believe, but be lacking in charity. In a sense that also describes those who believe but who are not in the state of grace because of unconfessed mortal sin. They are like the foolish virgins who get locked out of the wedding feast, or the one who says, “Lord! Lord!” but who will not, after all, enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church 546 mentions the parables about the feasts, explaining:

Jesus’ invitation to enter his kingdom comes in the form of parables, a characteristic feature of his teaching. Through his parables he invites people to the feast of the kingdom, but he also asks for a radical choice: to gain the kingdom, one must give everything. Words are not enough, deeds are required. The parables are like mirrors for man: will he be hard soil or good earth for the word? What use has he made of the talents he has received? Jesus and the presence of the kingdom in this world are secretly at the heart of the parables. One must enter the kingdom, that is, become a disciple of Christ, in order to “know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven”. For those who stay “outside”, everything remains enigmatic.

“Many are called, but few are chosen”, as the parable in Matthew ends. Why? Because they don’t make the radical choice to love, to give it all.

Let’s loop back to Sunday’s Epistle reading from the 1st Letter of John. John says that Love Himself, love incarnate came to us and laid down his life for us. What He did, He did in concrete action. We can’t just love in theory, we must love also in the concrete, in word, certainly, but also in deed. The people who refused the invitations in the parables made a concrete choice. The man without the garment was without the deeds of righteousness and without love, which was his choice.

If you are outside the banquet hall because you refuse to come, or if you are inside the hall but without the right disposition, the result is the same. You are not going to partake of the feast. The outer darkness awaits you.

I am minded of the fact that, until 1955, the Feast of Corpus Christ also had an Octave. That meant that the Mass texts for Corpus Christi were still very fresh in the eyes and ears of Mass hearers on this Sunday, just two days after the Feast of the Sacred Heart. Connect the reading from 1 John with the Sacred Heart:

By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us; and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren…. Little children, let us not love in word or speech but in deed and in truth.

Connect the fate of those in the banquet who are properly disposed or not properly disposed with the teaching in the Corpus Christi Sequence Lauda Sion:

Sumunt boni, sumunt mali:

Sorte tamen inæquáli,

Vitæ vel intéritus.The good partake, the bad partake:

with, however, an differing destiny

of life and death.Mors est malis, vita bonis:

Vide paris sumptiónis

Quam sit dispar éxitus.It is death for the bad, life for the good:

behold how unlike is

the outcome of like partaking.