The guy in the pope’s jacket

It’s a long trip from Chicago to Chiclayo.

There’s a direct flight from O’Hare to Lima, which after eight hours in the air, lands late at night in the Peruvian capital. Your flight to Chiclayo would be the next day, just two hours in the air, enough to see you land in the northern Peruvian city almost 24 hours after take off in Chicago.

From the airport to the cathedral is not very far at all. The airport sits on the west side of Chiclayo, a sprawling city of low-slung brick buildings and unpaved streets, middle class by some Peruvian standards, but very poor, from a U.S. point of view.

The cathedral is in the city center, with a lush green plaza in front of it, flanked by the city’s municipal building on one side, and some restaurants, and the bishop’s house, on the other.

St. Mary’s Cathedral in Chiclayo was started in 1869, with plans drawn up by Gustave Eiffel, a fact that locals are keen to boast about.

It’s airy inside, with big open doors on each side, letting breezes through, and high vaulted ceilings that leave the church cool enough to be a respite from the heat outside.

Inside the church, the sacristy is to the left of the sanctuary, behind a door marked “sacristía.” After Sunday Mass, hundreds of Catholics gather at the door, waiting for a priest to emerge, and with holy water on an aspergillum, to bless the rosaries, medals, and holy cards they hold aloft.

Inside, the sacristy is neat, with a long table at which priests read the paper or talk between Masses, and the set of counters, drawers, cabinets, and wardrobes familiar to clerics worldwide.

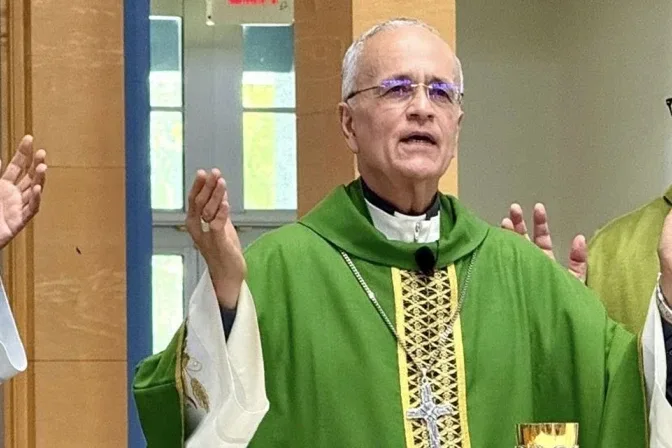

In 2014, Fr. Robert Prevost made the long trip from Chicago to Chiclayo. In Chiclayo, he made his way to that cathedral sacristy.

And that’s where he met César Cortavita.

Prevost was in his late 50s. Cortavita was 11. But they developed a friendship that shaped César Cortavita’s life — and one that may well say much about the man who is now Pope Leo XIV.

—

César Cortavita started serving Mass at the cathedral when he was seven years old, he recalls, soon after his First Holy Communion.

At a good pace, César lives a 20-minute walk from the cathedral, he’s in a neighborhood of mostly paved urban streets, in a small place with his grandmother, and a few of his siblings. His younger sisters live with his mother in another house, not too far from where César has grown up.

His grandmother is a woman of deep faith, and by all accounts, his grandfather was too. His mother carries that faith — she recalls to The Pillar that she prayed over each of her children, in their infancy, that they would become missionaries for the Gospel, and she tells the stories of walking with them in Eucharistic processions, when her children were just weeks old.

César’s home is simple, but welcoming.

Chiclayo’s urban neighborhoods lack stormwater sewer systems, and the streets flood during Chiclayo’s frequent rainy deluges. At César’s home, like at many of his neighbors, there is at the front door an eight inch brick curb, meant to keep the waters at bay. Sometimes the curb does the job, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Inside, César shows off pictures of his family, holy images — especially Señor de los Milagros — and mementos of his friendships with Chiclayo’s priests and bishops, especially the man he remembers fondly as “Monsignor Robert.”

The two struck up a friendship over years of liturgies at the cathedral at Chiclayo. César remembers that his former bishop was serious-minded liturgically — like him — but he didn’t get flustered by some practice or devotion he wasn’t expecting.

César says that Prevost urged servers and sacristans to know the rubrics, and to follow them carefully, and respectfully.

He says the pope wasn’t particular about vestments. In fact, the chasuble that became “his” at the cathedral was put out for Monsignor Robert just because it fit the bishop best — while Pope Leo’s 5’10” frame isn’t especially tall in Chicago, in Chiclayo, it’s tall enough to stand out.

César, himself serious minded about the faith — and usually loosening up only over foosball with his friends — liked serving Mass for Prevost.

He liked especially that Monsignor Robert would take a few minutes to pray before Mass, César remembers, making very little small talk before liturgies began.

But sometimes, if they had a few minutes waiting for Mass to start, Msgr. Robert would teach the servers a few English words as they stood quietly, or help them with English grammar if they were trying to learn the language.

After Mass, in the sacristy, Presvost’s tone would change — he would joke with the servers, and he’d quiz them, César remembers, about the Chiclayo dialect — trying to shake both his Lima lexicon, and his American accent — because “he wanted to talk like us,” César said.

“He wanted to talk like us. So he learned from the people of Chiclayo, and eventually, he sounded like us.”

Their friendship grew in the years at the altar together.

César recalled that on the day of his confirmation, Bishop Prevost acted confused when César arrived at the cathedral, making jokes that César wasn’t scheduled to serve Mass that day.

“It was a very serious day,” César said, “and that’s when Monsignor Robert likes to lighten the mood.”

César remembered that when they first met, Prevost would often mispronounce his last name, so that César would not always know the bishop was talking to him in the sacristy.

“He would be calling me by name — or think that he was — but I wouldn’t even know, until someone would say, ‘I think he is talking to you.’”

But in 2018, their friendship changed. That year, César’s grandfather — who had been like a father figure to him — died. It was a crisis for the whole family.

And Monsignor Robert was there for them.

César is careful to emphasize that Prevost wasn’t the only priest to minister to his family as they mourned. He is close to most of the presbyterate in Chiclayo — when priests see César on the street, they stop him for a hug, or conversation, and they check in with him about what’s happening in the cathedral. When he stops by their parishes, they greet him warmly, inviting him into their rectories for coffee or at least a step out of the sun.

Several priests were there for his family when his grandfather died. But Monsignor Robert was one of them.

“He would pray with us, and he was always making sure that we had what we needed, and he just listened. He would just listen to what we experienced, no matter how long it took.”

Prevost became for him a father figure, César said. For César, and his brother Sergio, and for their sisters, too.

That continued as César got involved in the cathedral’s youth movement, where he learned that Msgr. Robert’s missionary heart meant a heart for serving the poor. César recounts warmly standing with his friend as he served lunch to the poor, or as he traveled to flooded areas to deliver supplies, or as Prevost blessed oxygen plants he’d organized in the area during the pandemic, which hit Peru especially hard.

But mostly, César talks about Prevost’s ministry of presence —that he wanted to be with young people, the marginalized, or the suffering, and the way he rolled up his sleeves to get things done.

That, César said, is what made Msgr. Robert stand out as a missionary — that where Peru’s ecclesiastical culture might see a bishop put in places of honor, Prevost never wanted that. He wanted to be a pastor among ordinary people. He wanted to be a father among ordinary families.

—

If you walk Chiclayo with César, he’ll point out Msgr. Robert’s favorite restaurants, and where he had plans to restore old churches, and neighborhoods the pope visited during the city’s frequent Eucharistic processions.

It takes a bit more before César talks about the day Msgr. Robert was elected to be Pope Leo XIV.

But when he does, he remembers a phone call from a friend, who was ecstatic that César’s friend Robert was now the pope. He remembers sitting in the kitchen, in disbelief. He remembers saying some quick prayers for the new pontiff.

And he talks, quietly, about something he says might be a family miracle. César recounts that in the months leading up to the papal election, his grandmother had suffered from pains in her shoulders, and was scarcely able to raise her hands above her face.

On the day of the election, he says, the pains were gone. She raised her arms in celebration. The family wept.

Was it a miracle?

Well, César says thoughtfully, “definitely it was a special grace for us, at least.”

—

César told The Pillar he’s not sure what his own path is.

He’s completing a university education in music now. He knows God has called him to be a missionary — he’s known that for years, he said. Whether that means becoming a priest, he said, is up to God.

The path will be, without a doubt, influenced by his friend Msgr. Robert.

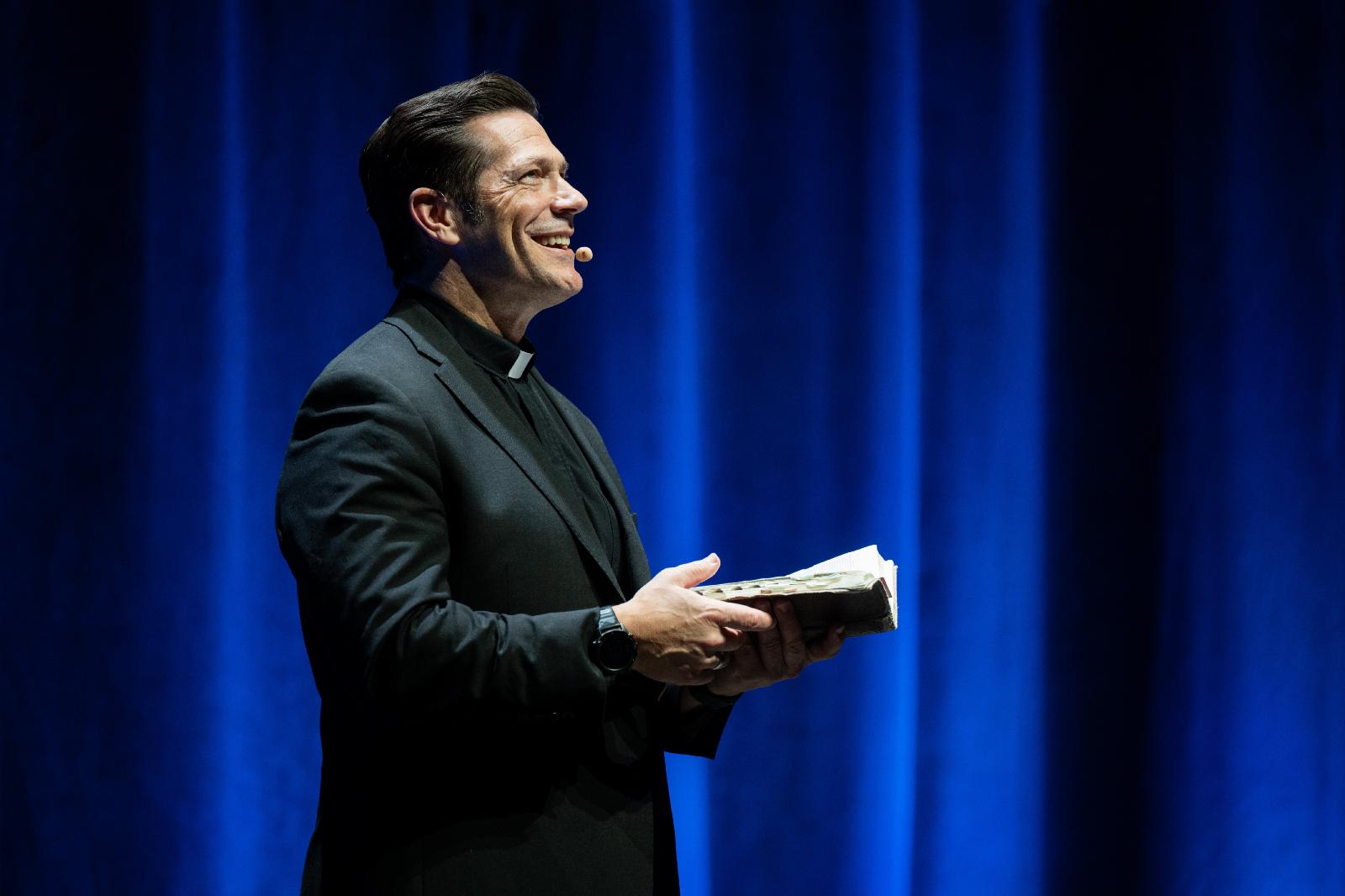

In fact, as he talks to The Pillar, César wears a jacket owned by Prevost — despite the heat of the day — which the pope gave away the day he was called to Rome in 2023 to become prefect of the Dicastery for Bishops.

If you owned a jacket that had been owned by the pope, you might boast about it — but César mentions it casually, in the context of a story, and only to make a point.

Of the clothing that Prevost was giving away, César said, that was the only jacket which fit his slight frame.

César expects a flourishing of vocations in the Leonine era of the Church, he told The Pillar.

“Because I think what kind of man he is, and what kind of priest, people will want to be like that. People will want the missionary life, the missionary heart for God, that he has.”