‘We are fully sustainable’ - The rise of Catholic microschools

At the beginning of the school year in autumn 2022, St. Athanasius had $8,000 in the bank, a $4,000 bill, around 80 students enrolled, and a brand new principal.

The small Catholic school in Long Beach, California was on the verge of shutting down — and it was Sonia Nuñez’s job to save it.

She took out a $5,000 payroll loan, hired new staff members and announced that the school would be switching to a microschool model — grouping multi-age students in the same classroom.

Under the new model, the number of classes was reduced from 10 to five, staffing was cut in half, and Nuñez focused on learning the names of all 82 students.

—

Four years later, enrollment has increased by 20 students, test scores have improved dramatically, parents are more engaged and the school ended last year with $100,000 in the bank.

“Microschooling was a last-ditch effort to save the school financially,” Nuñez told The Pillar. “Now, we are fully sustainable. We have gone basically from so deep in the red we almost had to close our doors, to the black now.”

“Our students were not receiving curriculum at their grade level but when we started teaching in the multi-grade classroom approach, we saw test scores starting to go up,” Nuñez added. “We have also noticed that the current second graders who are the students that have had nothing but microschooling are the highest performing students in the school.”

Microschooling is an approach for institutions with fewer than 150 students; it involves teaching students in multi-age classrooms, where teachers focus on teaching to individual students, rather than the class. The National Microschooling Center reports that there were 800 registered microschools as of May 2025.

The center reports that 50% of microschools are private centers serving homeschooled students, 30% are private institutions — including Catholic schools, 5% are charter schools, and the other 11% split among other structures.

The center notes that a microschool’s defining elements ”are innovative small learning environments, which have generally been established outside of traditional public education systems.”

The data

St. Athanasius is one of five microschools in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and one of the 22 Catholic microschools in the United States that has registered with the National Catholic Educational Association.

There are others, even if they’re harder to count — independent classical institutions like Chesterton Academies, or homeschooling co-ops.

The pandemic altered the landscape of Catholic education as both homeschooling and Catholic liberal education grew in popularity. Since the pandemic, microschooling has become a growing trend across the United States in both Catholic and secular circles as more small schools faced the prospect of shutting down.

There are 5,852 Catholic schools in the country, 30% of which have 150 students or fewer.

In the 1960s more than 5 million students attended Catholic schools — a high point for Catholic education. But since then, enrollment has dropped. Ten years ago there were 1,939,574 students enrolled in Catholic schools according to the National Catholic Educational Association. Today, there are 1,683,506 students.

A decline of more than 250,000 students in one decade is no small thing.

And according to data released by the NCEA, that declining enrollment meant that in recent years, about 100 U.S. Catholic schools have closed annually — and in 2021, 209 schools closed across the country, the most in any year.

During the pandemic, as hundreds of Catholic schools faced closure, Dr. Jill Wierzbicki, a former vice president at NCEA, and Dr. Kevin Baxter, former superintendent at the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and former NCEA chief innovation officer, aimed to address the issue.

The two researched microschools for their book: “Greatness in Smallness: A Vision for Catholic Microschools.”

“The traditional mindset is that if a school has [low] enrollment you ask, where do I find more kids?” Baxter told The Pillar. “Sometimes, that’s a really good approach. But in our world today, kids might just not be there, or there might be factors at play preventing a boost in enrollment.”

“Thus we started thinking about this more intentionally, asking if there was a way we could start to plan more thoughtfully about how to help schools sustain themselves, if their enrollment was not going to be sufficient [to support a traditional school model].”

Microschools seemed to be the answer — at least as Wierzbicki and Baxter saw it.

“It is almost like we put the cork in the sinking ship,” Wierzbicki told The Pillar. “We found a way to greatly decrease the number of closures. Once we published the book, suddenly people were talking about their smaller schools differently. They saw an option that wasn’t an immediate closure.”

After the pandemic, Catholic school closures have decreased with 71 closing in 2021-2022, 37 between 2022-2023, 55 between 2023-2024 and 63 between 2024-2025.

“We were closing a few hundred schools in 2019, 2020, 2021,” Wierzbicki said. “Then it got down to like two digit numbers, as soon as we started talking about microschooling.”

As dioceses continue to address declining enrolments, Baxter believes they should consider microschools, before presuming they’ll need to close or merge schools.

“Each parish and school has its own identity, and they want to maintain that community, and they want to continue to serve the community that they’ve served for generations,” Baxter said. “The microschool model says to those schools that you do not have to do a [merger] approach. You can keep school distinct from each other, by moving to a model that can create sustainability.”

The strategy

When launching a microschool, administrators focus on three areas: Catholic identity, academics, and operational standards, Baxter said. Those pillars help guide the microschool’s direction and encourage a healthy relationship with the parish, a necessity for success.

For success, administrators must be intentional about developing both a unique academic and financial strategy.

“When considering the economics of a micro-school, they need to be disciplined in terms of staffing and ensuring they do not have excess in terms of people,” Baxter said. “The ideal is to have a model where parents wouldn’t be paying anything significantly more than another local Catholic school.”

Strict budgets become key to running microschools, as every dollar counts, but the budget must allow the school to scale in size, while keeping tuition costs reasonable enough for families to enroll.

“The key is making sure that you have access to professionals in finance and in business management who manage the books for the school and the parish in a way that allows you to scale a budget,” Wierzbicki said. “You can scale any budget based on student size as long as you understand the components of your budget.”

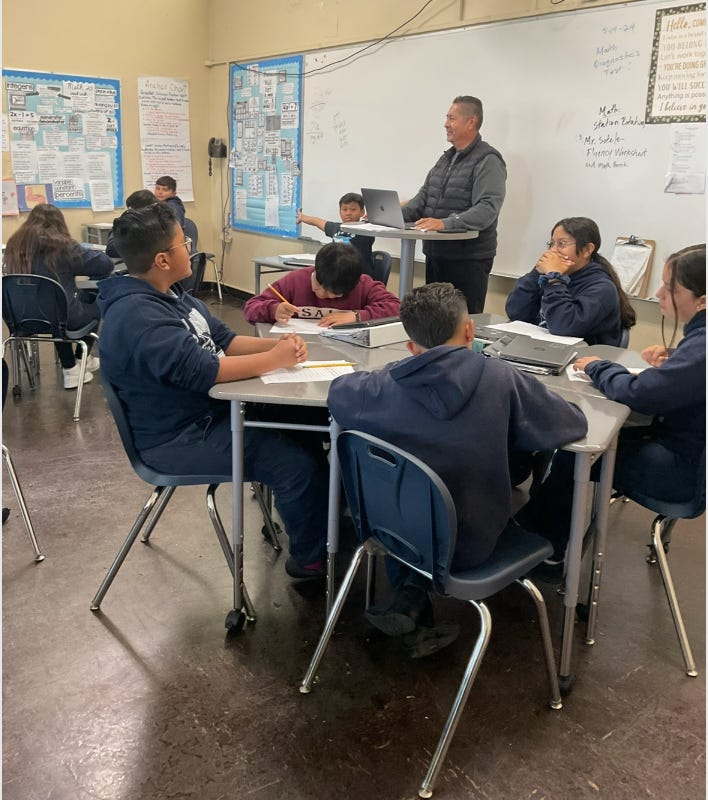

Academically, teaching a multi-age class differs from contemporary teaching models. It offers an almost “one-room schoolhouse approach” to learning, experts say, forcing teachers to develop a more individualized approach to educating each student.

“Putting kids together to learn together is really the opposite of what we saw in the Industrial Revolution of having everyone of the same age turn to the same page at the same time. But real learning doesn’t look that way,” Wierzbicki said.

“Allowing kids to self-pace, to achieve mastery before they move on to something else is so much more conducive to learning.”

While not a necessity, utilizing and incorporating technology can help both teachers and students thrive in a mutli-age classroom.

“Adaptive, curricular technology allows there to be a scope of reading capacity within the same classroom because they are all getting exactly what they need when they sit down in front of the screen and the technology program gives them independent, individualized work,” Baxter said. “They are getting challenged wherever they are to grow and to learn and to improve, but the teacher doesn’t need to differentiate everything for every individual child.”

The experience

Microschools have popped up across the country, both in rural and urban areas. One of the largest supporters of microschools has been the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, the largest Catholic diocese in the country both by population and Catholic schools. Five of the archdiocese’s 250 schools are microschools.

“The idea behind the microschools was to ensure that students received a truly personalized, individualized education that supports their unique academic needs, but also and fundamentally brings them into an encounter with Christ,” according to Robert Tagorda, chief academic officer for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

This change also came as a financial necessity as many of the schools — many in impoverished areas — struggled to remain solvent with declining enrollment in the years before and during the pandemic.

“They all came upon a really critical point in their school community’s history, in which they had to ask themselves what would be the best path forward for a school with low enrollment,” Tagorda told The Pillar.

St. Athanasius serves a poorer, mostly Hispanic community in an area with few options for affordable, Catholic education.

“We are the only affordable Catholic school in a very, very rough neighborhood where the public schools are just bad. Some of these kids that come from public school come scared. They’re scared to go to school,” Nuñez said. “But after a few weeks here, the students feel safe.”

While microschooling has increased in popularity post-pandemic, it is not a new phenomenon. St. Joseph School, part of Divine Providence Academy, in Conklin, Michigan, has been operating as a microschool for 15 years. The school serves a rural parish, which experienced declining student enrollment for decades.

Gina Bouwhuis told The Pillar that the model at St. Joseph had a tremendous impact on her son.

“The school partnered with the local Catholic high school, and he was taking high school classes in eighth grade as the multi-grade level had prepared him so well,” Bouwhuis said. “They were continuing to be challenged and were able to meet people that would be their classmates the next year. It got them very prepared for high school.”

Beyond academics, the microschool helped Bouwhuis son foster deep, intentional relationships with his classmates — friendships that he still maintains today, at 25 years old.

“He still sees five or six kids that he went to grade school with regularly, which is almost unheard of for most kids,” Bouwhuis said. “The relationships that they’ve made are pretty impressive.”

The Bouwhuis’ experience is not a novelty.

Gina Bouwhuis, who now works as a student resource teacher at St. Joseph, sees students from a range of academic levels thriving at the small school.

She said the model allows flexibility in instruction, according to the needs of each student.

“They are not working at a level that’s above or below where they are at — students are working at their ‘just-right’ levels in small groups,” Bouwhuis said. “The kids who are high flyers can keep on moving. The kids who are right where they need to be can keep moving at a steady pace and the kiddos that need a little extra help or a little extra time, get that extra time.”

Across the country, microschool administrators and teachers report students performing above average on standardized tests, attributing success to small class sizes and the mutli-grade model.

Holy Trinity School in Westmont, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, adjusted to the microschool model two years ago. A 2024 standardized test for K-8 students indicated that 45% of students were at or above grade level in reading and 39% in math. But by spring 2025, scores increased to 82% in reading and 79% in math.

“Our standardized test scores were great last year,” Dr. Pamela Simon, principal at Holy Trinity School told The Pillar.

“Across the board, the students are learning, they are growing academically, and I think everybody in the building has seen the social growth and just the joy that the kids feel in being in school.”

Since adjusting to the microschool model, Jessica Paulsen, a middle school teacher at Holy Trinity School has seen a huge transformation in students, not just in academic performance.

“Microschooling really offers the opportunity for our older seventh and eighth grade students to show leadership. For example, sixth graders are assigned an eighth grade buddy, who is helping them make that transition to middle school and just be supportive to them,” Paulsen said. “Since we are one class, it instills that we’re one community, and we have students that will help each other learn and work together.”

This model also encourages students to become more independent and accountable for their own learning.

“Students learn how to advocate for themselves in this environment,” Simon said. “When they need something, they know to go to the teacher and ask for it specifically and know what to ask for and how to ask for the right things so that they can facilitate their own learning.”

Compared to same-grade educational models, Paulsen said that she has had to be more intentional with the students and spends more time working with students one-on-one and in small group settings.

Currently, Paulsen’s 6th, 7th, and 8th grade classroom is doing a poetry unit, where students are studying “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe. At the beginning, Paulsen provides the same lesson on the basics of poetry. Then, she splits the class into their grade levels to read specific, grade-appropriate excerpts of the poem. And if younger students are excelling, Paulsen is free to move them to a higher reading group.

“If I was teaching at just one of those grade levels, I would focus on one poem, what type of figurative language they are expected to understand at that level and provide practice and then assess,” Paulsen said. “However, within a multi-age environment, what I’m able to do is as a whole group we are learning how to annotate, we are learning some background about the poet, but then we are breaking off into smaller groups where they will receive age-appropriate poems as smaller groups.”

“There’s a lot of interchanging between groups and really looking at their individual needs,” Paulsen added.

At Divine Providence, teachers give the class pre-unit tests, testing students on knowledge of upcoming class content. When students score 100% they move on to the next unit. If they miss one or two questions, they’re given instruction in the areas where they struggle. If students show a need, they receive instruction for an entire chapter.

“There might be some chapters where some students need just a little bit more time and more practice with a concept before they can move on,” Bouwhuis said. “All of the kids know that they are all at different places at different times, and it’s okay because that’s just, to them, normal.”

Tuition remains on par with other Catholic schools administrators pay. Tuition at St. Athanasius is $4,071 annually , Divine Providence is $4,750 for parishioners and $5,750 for non-parishioners, and Holy Trinity is $5,485.

“Tuition has been increasing steadily over the last several years by the amount that our faculty gets a raise. And so they’ve been doing cost of living raises,” Simon said.

“But we have contracted a little bit on the budget side. We had a teacher move to Philadelphia, but we did not replace her because our class sizes are still quite small. So we’ve contracted a little bit on the expenditure side of the budget to make sure that we remain financially viable.”

Microschool advocates say that it’s not just the students that are benefiting from this model — parishes and parents also benefit from the model.

“We have more parent involvement. We have more parent led activities. We have an active PTO once again,” Nuñez said. “Parents see that their students are learning and the kids are happy, the parents are happy and it brings them out into the community.”

This increased participation might be associated with the small class size, and that students often have the same teacher for multiple years.

“Microschooling allows for deeply personal learning experiences for their kids so both the students and the parents are really getting to know their teachers,” Tagorda said. “Because the teachers are serving at least two grade levels, it means that the families will truly get to develop a strong working relationship and partnership with that teacher over the course of the two or three years.”

Parent involvement is the sign of a healthy microschool, Wierzbicki said.

“A strong Catholic microschool has a leader who understands that parents are the primary educators of their children,” Wierzbicki told The Pillar. “If they are partnering with families and families are trusting this place as an extension of the home to teach their children and when everything’s in that correct order, this is a very successful model.”

Microschools encourage creativity both in their approach to parent-teacher relationships and in education strategies as faculty experiment with best educational practices.

“The trademark of these microschools is that they are able to serve students from different grade levels within a single setting,” Tagorda said. “Those practices have helped to create some of the personalized learning experiences which we have shared with our non-micro schools.”

“Our microschools have been sources of innovation, almost like a research and development laboratory.”

As dioceses and pastors grapple with declining enrollment, current microschool principals and administrators see this model as a viable model — it just requires that leaders challenge the education process.

“Bishops, superintendents, and even philanthropists should not just look at enrollment as a measure of school success or sustainability,” Baxter said. “What we’d rather do is look at the faith outcomes, academic outcomes, social growth and look at those measures when determining the health of a school and don’t simply say that enrollment is the sole factor that indicates whether a school is successful or not.”

“We have to be more creative about this.”