A Baseball Fan Answers: Should Confession Ever Be Delayed?

Theodore Samuel Williams, aka the “Splendid Splinter,” was my childhood hero. He was, without a doubt (at least in my imagination), baseball’s greatest hitter of all time. And he had the statistics to prove it. His .406 batting average in 1941 has yet to be approximated after 85 years.

Williams was a controversial figure. People of outstanding accomplishments often are. He did not always get along with the Press. He was, in as anonymous a way as possible, a generous benefactor, both in time and money, to the Jimmy Fund, an organization which aided children who battled with cancer. He was distinguished both on and off the field.

There was something magnetic about Williams. He was an idol of many Red Sox fans who, although often frustrated with their team’s disappointments, never lost faith in “Teddy Ballgame.” It was far more important to them how Williams did rather than how his team fared. He transcended the sport. In his Hall of Fame speech, he tipped his cap to the Creator: “To me,” he said to his admirers, “[baseball] was the greatest fun I ever had, which probably explains why today I feel both humility and pride, because God let me play the game and learn to be good at it.” Well, in my mind, he was more than good. He was inimitable.

We were poor back in the forties and fifties, but poverty can ignite the imagination. I wondered what the perfect hit would be and hoped that Number 9 would be at the plate when it happened. I imagined a team trailing 3-0, with two outs in the ninth inning, bases loaded. Then, Mr. Ted Williams would stride to the plate and win the game by hitting a Grand Slam. It was a dream that might never happen. Perfection may be pursued but never caught. Or would it? “Dreams can come true, it could happen to you,” as the song says.

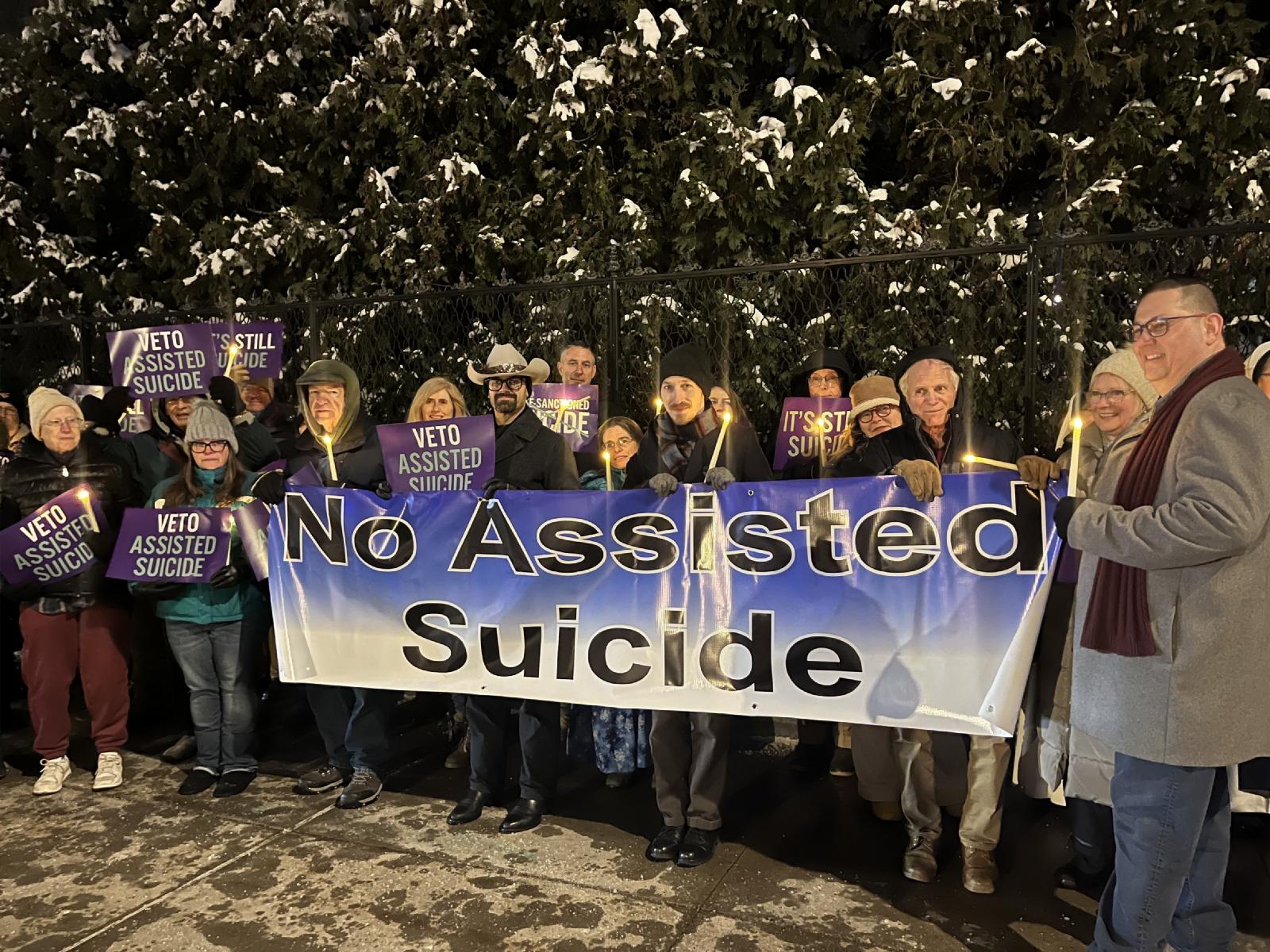

It was Saturday, August 27, 1955, at Briggs Stadium in Detroit. The Tigers were leading the Boston Red Sox by three runs with two outs in the ninth inning. Three Boston players stood at the respective bases, hoping the improbable, as Ted Williams came to the plate. And at precisely this moment of excited anticipation, while my eyes were glued to the television screen, my mother said to me, “It’s time to go to confession.”

“But, mom, it’s the ninth inning, and there are two outs. The game will be over very soon.” My passionate plea earned a brief reprieve.

Frank Lary had pitched a masterful game for Detroit that sunny day, allowing but three singles. With a shutout going with only one out left to win the game, manager Bucky Harris decided to bring in a left-handed relief pitcher, by the name of Al Aber, to face the left-handed hitter, Ted Williams. It was a reasonable but questionable move.

Back at home, my persistent mother who had minimal interest in the fate of the Boston Red Sox said to me, “Oh they are bringing in another pitcher, you better get to confession before it is too late.” Maybe I was more obedient to my mother’s command than I should have been. I went to confession, recited my non-sins to a bored priest who charged me three Hail Marys for their remission and wondered what Williams did in that ultra-dramatic situation.

As I was leaving the Church, I met my brother, Ricky, who was on his way to confession. He was not a fan of Boston’s leftfielder. “Ted Williams is a muttonhead,” he once said. In a less-than-enthusiastic tone, he told me that Williams hit the grand slam homerun, the clout that I had long dreamed of. The Red Sox won 4-3. I missed the moment but read the record. This is what transpired:

Aber’s first pitch went for a ball. Williams fouled off the second pitch. Another ball followed. Would Aber walk the indomitable Mr. Williams? If he did, only one run would score. Jackie Jensen was the next scheduled hitter. At the time, he was sporting a modest .276 batting average.

The fourth pitch made history. Arthur Simpson of the Boston Herald saw what my own mother did not allow me to see and wrote, “Mighty Casey DID NOT strike out.” If I may modify Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s famous poem, “Somewhere people are brooding, somewhere people pout, but there is JOY in Boston, for the mighty Williams gave the ball quite a clout.”

With his quick wrists, Williams launched a high fly ball halfway into the upper deck of the right-field stands. It was truly a memorable moment in baseball history. I may not have witnessed it, but I have had the privilege of recording it, and in a theological context. I can forgive my mother since she was merely fulfilling her motherly duty.

Williams would hit another grand slammer against the Tigers, again at Briggs Stadium, on July 29, 1958, against Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Bunning. It would be his 17th, tying him with Babe Ruth and placing second in that category only to Lou Gehrig, who hit 23rd for the number one spot in career bases-loaded home runs.

My answer to the question, “Should confession ever be delayed” is a resounding “Yes,” though under the right circumstances. Indeed, sometimes delayed, but never avoided.