Joseph of Arimathæa artefact at V&A offers rare window into ‘how England really looked’ in Middle Ages

“And after this Joseph of Arimathæa, being a disciple of Jesus, but secretly for fear of the Jews, besought Pilate that he might take away the body of Jesus: and Pilate gave him leave” (John 19:38). The Victoria & Albert Museum has launched a campaign to save an exquisite 12th-century ivory carving of the Deposition The post Joseph of Arimathæa artefact at V&A offers rare window into ‘how England really looked’ in Middle Ages appeared first on Catholic Herald.

“And after this Joseph of Arimathæa, being a disciple of Jesus, but secretly for fear of the Jews, besought Pilate that he might take away the body of Jesus: and Pilate gave him leave” (John 19:38).

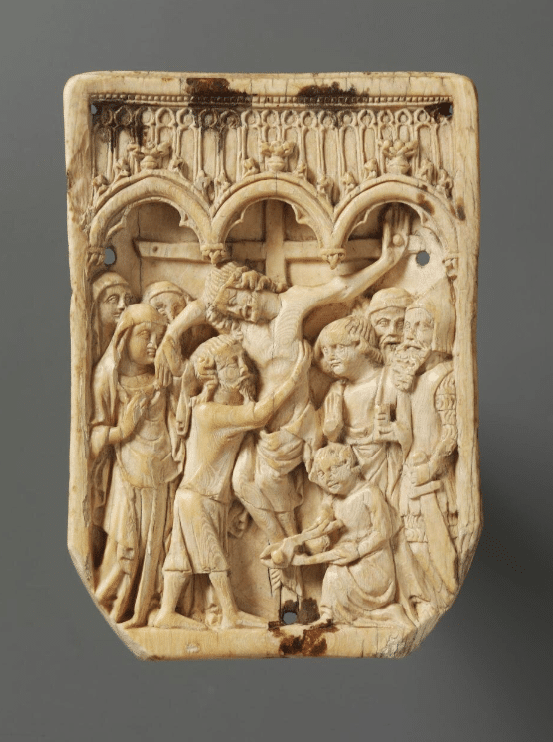

The Victoria & Albert Museum has launched a campaign to save an exquisite 12th-century ivory carving of the Deposition of Christ for the nation. For many years this piece was an integral part of the displays in the museum’s Medieval and Renaissance Galleries, on long loan from a private owner. Imbued with breathtaking emotional intensity, its visceral depth of expression is rendered in the face of Joseph of Arimathea, whose compassionate eyes gaze up at the slumped figure and lifeless face of Jesus. Here is the figure that has “begged” for the body of Jesus, and to whom Pilate has granted it as the daylight fades.

This remarkable treasure provides a glimpse of the refined creative output from a period of artistic production where, before the flourishing of the gothic style in the mid 13th century, the human figure was imbued with a solidity of form that evoked the classical past. Christ’s humanity is emotively imparted through His very dead body, limp and slumped in the arms of Joseph. The artist’s interest in the figure is revealed by the heavy drapery that provides a tangible sense of the body mass underneath.

The emotional charge and composition of the “figuregroup” was itself a relatively new iconography at this time, the prototypes of which originated in the art of Byzantium, spreading to Europe by the mid-12th century. The pathos found in the face of Joseph and the body of Christ echoes Byzantine renditions of the same subject. The hypostatic nature of Christ’s identity as both God and Man was an important theological truth to stress in the face of the contemporaneous Albigensian heresies which denied His divinity and the Virgin Mary’s role as God-bearer.

The passage of such iconography across Europe further reminds us of the internationalism that was apparent in late-12th-century society. Artists, patrons, pilgrims, merchants traversed the Continent, while the Fourth Crusade culminated in the occupation of Constantinople in 1204. England was itself part of the Plantagenet realms that included roughly half of the landmass of modern-day France, including the lands of Aquitaine.

The walrus ivory used for this carving is a reminder of the resources available to artisans in England at a time when the use of elephant ivory was rare. The walrus tusks, also used in Scandinavia, remind us of the strong connections in art and style that were also transmitted across the North Sea. The stretches of water between the coastlines that provided the walrus with its habitat offered the swiftest and safest form of travel for a long-distance medieval journey.

The sculptor who created this remarkable work of art was a master of the craft, and exploited the slender tusk to compliment the composition. Its natural curvature provides the graceful curve of Christ’s spine. The malleable material has permitted the carver to create captivating details: the thick waves and curls of Christ and Joseph’s hair, the ghostly ribs of Christ’s torso, His toes and heavy hanging hands and the thick folds of drapery that wrap around His fragile frame.

In doing so the artist invites the viewer fully to participate in the narrative and quietly to contemplate the Passion of Christ: “Of the glorious body telling, O my tongue, its mysteries sing…”

Arabella Illingworth read art history at Edinburgh.

Why the Joseph of Arimathæa artefact is a national treasure

The systematic and sustained outbursts of iconoclasm that accompanied both the Reformation and the Cromwellian revolution mean that it is almost impossible today to reconstruct with any great accuracy how England really looked in the Middle Ages. The visual record has all but been obliterated. This is true of our monumental structures such as churches, abbeys, monasteries and cathedrals – mere shadows of their splendid past when they were ornamented with stained glass, sculptures, wall paintings and tiled floors – but it is even more the case with portable art that was frequently contained in treasuries glittering with gold, silver and precious gems.

For 40 years, the V&A has been the guardian of the loaned “Deposition from the Cross” – an entrancing and deeply-moving 12th-century walrus ivory carving. Ripped from its original setting in an iconoclastic frenzy, the scene of the Deposition was brutally abbreviated to leave only the figures of Joseph of Arimathea and Christ. This makes the ivory an exceedingly rare survival of English medieval devotional art. Indeed, the damage wreaked on the Deposition’s wider scene has endowed the work with even greater emotional impact.

Originally the Deposition would probably have included figures of the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist. St Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus, usually seen removing the nails from the cross with a pair of pliers, might also be represented. The account of Joseph of Arimathea’s generosity and compassion in caring for the body of Christ is related in all four of the canonical gospels. It was utilised by artists to engender empathy with the suffering of Christ in the moment of His death.

The carver responsible for the Deposition has captured the tenderness and reverence with which Joseph cradles the slumped body of Christ as he takes it from the Cross. In a beautifully observed stroke of naturalism, Joseph’s right knee buckles slightly under the weight, expressing the physical reality of Christ’s human presence.

Made in the final years of the 12th century, probably in York, this mesmerising sculpture relates closely to a smaller fragment in the V&A’s collection which shows Judas receiving the Sacrament from the hand of Christ at the Last Supper. It is generally considered that the two fragments were once part of the same artwork, probably an altarpiece, which is why it makes so much sense to keep these two great works of medieval sculpture together.

The Judas fragment was reportedly found during the demolition of a building in Norgate, Wakefield in 1769. With the ruthless destruction of religious art in the Reformation came attempts by the devout to secrete whatever they could salvage. Numerous finds beneath the floors or within the walls of ecclesiastical and domestic buildings testify to this widespread practice. While we have no record of the whereabouts of the Deposition before the 20th century, we can assume that its miraculous survival was through just such an act of devotion.

The V&A is hoping for similar such acts of devotion to retain this entrancing, wondrous work and the vanished Catholic culture it embodies; we need to raise £2 million to retain this elemental work of pre-Reformation, English devotional culture in the UK. After being withdrawn from our South Kensington galleries for a private sale to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the rarity and beauty of the Deposition convinced the British government to impose a temporary bar on its export to allow the V&A to launch a public fundraising campaign to keep it on show, for ever, for everyone, and for free.

Tristram Hunt is the Director of the V&A.

This article first appeared in the April 2024 issue of the Catholic Herald. To subscribe to our multiple-award-winning magazine and have it delivered to your door anywhere in the world, and receive our limited-time Easter offer, go here.

![]()

The post Joseph of Arimathæa artefact at V&A offers rare window into ‘how England really looked’ in Middle Ages appeared first on Catholic Herald.