Eyes Wide Open: A Chestertonian Exhortation

Rise thou that sleepest, and arise from the dead: and Christ shall enlighten thee. –Ephesians v. 14 We Catholics live in a world that is weary of itself and awaits liberation. A new calendar year dawns, and yet the same […]

Rise thou that sleepest, and arise from the dead: and Christ shall enlighten thee. –Ephesians v. 14

We Catholics live in a world that is weary of itself and awaits liberation. A new calendar year dawns, and yet the same old thing is true. Indeed, the Apostle writes, Every creature groaneth and travaileth in pain, even till now (Rom viii. 22). Yet not only is the world encumbered in this tiresome affliction, but even our own souls suffer in this manner. Which is why the Apostle elaborates: And not only it, but ourselves also,…even we…groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption of the sons of God, the redemption of our body (Rom viii. 23). There is something about living in the world that tells those of us who live for God that this world is not enough. It is not the end for which we were made. We were made for more. We are convicted daily that though we live in a world of endless vice and dreariness, God causes all things [to] work together unto good, to such as, according to his purpose, are called to be saints (Rom viii. 28).

Sainthood is what God calls every baptized Catholic to join. Yet, if we are indeed to be saints, we must become different from the world by ceasing to sleep. Whereas the rest of the world is numb to virtue and writhes in agony because it is lost, we Christians have a hope in a Savior who, having been truly Risen from the dead, awoken from seemingly eternal deathly slumber, says to all who hope in Him: Behold, I make all things new (Apoc xxi. 5). It is this newness of Eternal Life that we must awake to. Our Blessed Lord wishes to rouse us from our sleep of sin and self-medicating and give us Himself—the only true remedy against the drowsy snares of death which have hold of our souls.

There are many vain philosophies, mystical systems, and supposedly wise gurus we could ascribe to if we are not careful—deadly sedatives that could deter us from serving the Lord. Indeed, in our foolish wisdom of the age, we’d like to think that all religions are the same. This indifference is not wisdom, but rather a cowardice that refuses to acknowledge the Light. It keeps our souls entranced in a stupor that, at its worst, rehearses the damned credo of the Evil One: Non serviam. I will not serve. When we continue to sleep, we are in active state of rebellion against the Creator of the Universe. Satan wishes all souls to be asleep so that we would not awaken unto God. Thankfully, he and the other servants of darkness will never win against the Light which wakes souls to their salvation. For this Light? He shineth in darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it (Jn i. 5).

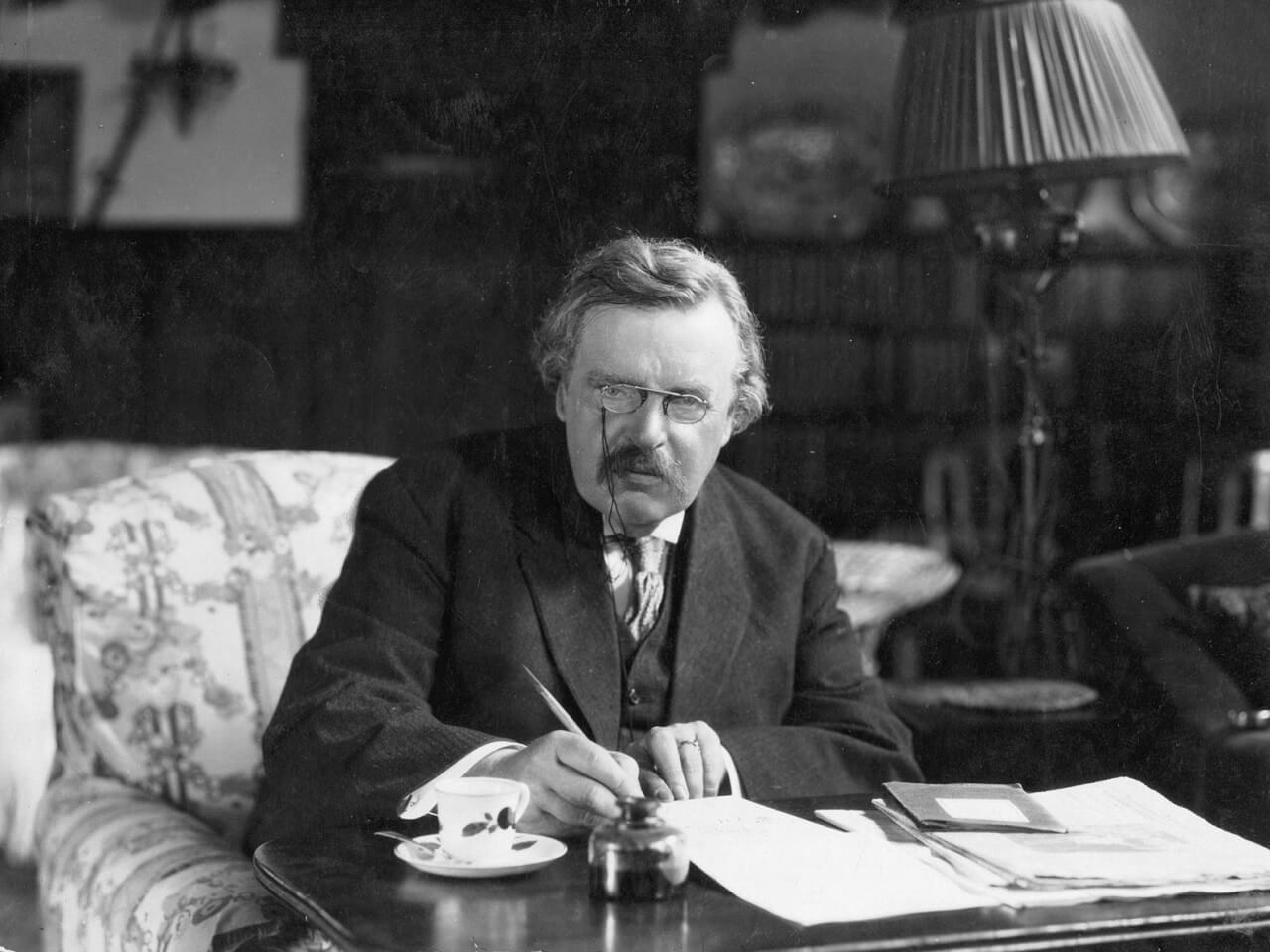

G.K. Chesterton, a convert to the Catholic Faith, knew this principle of Christianity to ring true. The saint differs from the world insomuch that he is awake. In his crucial work, Orthodoxy, the prince of paradox wrestles with the indifference of the age which thinks all faiths the same. There comes a point in his volume where he compares Buddhism and Christianity. Because Chesterton had studied art and was a regular artist who created, he found a key difference in how the Buddhist and the Christian saint are depicted in art.

Per Chesterton:

Even when I thought, with most other well-informed, though unscholarly, people, that Buddhism and Christianity were alike, there was one thing about them that always perplexed me; I mean the startling difference in their type of religious art. I do not mean in its technical style of representation, but in the things that it was manifestly meant to represent. No two ideals could be more opposite than a Christian saint in a Gothic cathedral and a Buddhist saint in a Chinese temple. The opposition exists at every point.[1]

And what, according to Chesterton is the crux of the matter between the Oriental and the Christian? He explains further:

Perhaps the shortest statement of it is that the Buddhist saint always has his eyes shut, while the Christian saint always has them very wide open. The Buddhist saint has a sleek and harmonious body, but his eyes are heavy and sealed with sleep. The mediaeval saint’s body is wasted to its crazy bones, but his eyes are frightfully alive. There cannot be any real community of spirit between forces that produced symbols as different as that. …The Buddhist is looking with a peculiar intentness inwards. The Christian is staring with a frantic intentness outwards.[2]

The crazed and frantic appearance of the saint startles and is uncomfortable to our modern sensibilities. One looks at the saints of the Early Church and can see that the life of the Christian is one that is wanting of comfort. The flayed skin of St. Bartholomew frightens us, the volley of arrows protruding from St. Sebastian’s body tied to the tree warn us that we may have to die if we follow Christ; indeed, we may lose our head for Him like St. Paul did. And, if we are truly following in the footsteps of the Saviour, we may have to be like St. Peter and be crucified just as the Lord was.

Yet for the saint, the threat of bodily death is a mark of victory, not defeat. In our martyrdom and witness for Jesus, we are perhaps most vivacious—for our eyes have been opened to the Truth which preserves our souls, and even the shuttering of our eyes in death cannot take Him away from us. The Christian credo urges the Christian to live for others and so he is happily forgetful of self. Like our Master, we lay down our lives for others in testament to the fact that there is a greater life ahead of this present vale of tears. This is because Our Lord gave us an ultimatum that we may never neglect: He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world keepeth it unto life eternal (Jn xii. 25).

This separateness from the world that belongs to the Christian saint, his indifference to keeping his earthly life because there is something greater to behold? This is the fuel keeping him awake. Chesterton, in a last word on the difference between the Buddhist and Christian, says this:

The Christian saint is happy because he has verily been cut off from the world; he is separate from things and is staring at them in astonishment. But why should the Buddhist saint be astonished at things?—since there is really only one thing, and that being impersonal can hardly be astonished at itself.[3]

At a time in history when all seems thrown into chaos in the world, in the state of the Church, and even in our own day to day lives, there is always a decision for us Christians to make. We can either go on dreaming senselessly to avoid pain, or we can embrace the Holy Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ. In the Cross there is pain, yes, but only in the Cross is there salvation. Rather than grumbling or being in perpetual state of woe at how bad things are, we must rise to the challenge. In a way, things have always been hanging off the edge of the precipice. The world has always been in a state of disarray and darkness because it has rejected the Light Who alone can save men from themselves. It is not up to us to solve every temporal problem; however, neither is it up to us to avoid every temporal inconvenience. We pick up the Cross and tread after Our Lord on the Via Dolorosa to be crucified at Calvary. Yet our eyes are never shut. We look on to the prize that shall be won atop of Golgotha, and though we may stumble on our way there, in our spirits we press on; indeed, in our hearts on this pilgrim journey we must run towards salvation. As the Apostle writes: So run that you may obtain (I Cor ix. 24).

We obtain the prize by being crucified with the Lord at Calvary. His Sacrifice is infinite and has primarily won the battle for all those who refuse to be complacent in their slumber. By keeping awake and responding to the Lord, embracing the trails and pains set out in this course to sanctify our souls, we will find victory by aligning our lives to Him. This is precisely accomplished in us by dying for, with, and through the Cross. It is only then by identifying ourselves with this salvific mystery that we will find the end of this painful Truth: namely, our rising from the dead in His Glorious Resurrection. Eternal Life can only be found by giving our earthly lives away.

Not all of us will be martyred in the bloody way as many of the saints were in the Early Church. Perhaps the Lord will call on us to die in such a manner in the age, but even for those of us who seem to have a mundane life, there is always an opportunity to give ourselves away to others for the sake of the Gospel. Our journeys are as such that we must in our pilgrim struggle find a way to die daily (I Cor xv. 31). For what is in this cycle of conforming ourselves to the Life, Death, and Resurrection of the Lord? There is true rest because we are awake to Him who alone can give eternal refreshment for our souls, sustaining them in Himself. Chesterton’s musing on the Buddhist and the Christian saints depiction in art has stuck with me for many years and encouraged me in my own race towards the prize which is in Christ. I hope it has encouraged you. Together, brethren, let us be happily and frantically awake—alive to Him Whom we hope to behold forevermore in that City where He alone is the Light (Apoc xxi. 23).

It is at this time of year above all that we see indeed that Light which shines in the darkness about to be manifested at Epiphany. Until then, Merry Christmas!

[1] Chesterton, G.K. Orthodoxy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 138.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 140.